3D Printing Risks: Not Just Plastic Guns, But Military Parts, Drugs And Chemical Weapons

The first successful test of a 3-D printed gun last month sent chills down many of our spines. What’s the use of background checks if people can simply make guns themselves with production devices in their homes?

But experts point out these weapons may be hard to perfect and perhaps they are not what we should be worried about right now. Indeed, the more immediate and far-reaching promise and perils of 3-D printing -- or “additive manufacturing,” if you’re a purist -- could lead us all to conclude that by comparison these plastic guns are just child’s play.

For example, 3-D printing already allows you to fabricate new, lightweight parts for aircraft -- and that can significantly cut fuel consumption. But it also opens the door to making counterfeit parts for commercial or defense operations, designed for sabotage. And the advent of bioprinting (printing with biological materials, including cells and tissues) expands the possibilities even further. Today, we can print ears, as Popular Science reported; in the near future, a terrorist might be able to print ricin.

“Every technology can be used as a double-edged sword,” Virginia Tech researcher Thomas A. Campbell told International Business Times. “The same thing occurred with the Internet; the same thing occurred with cell phones.”

Part of Campbell’s job is to think about the fast-evolving nature of 3-D printing, particularly in the field of counterfeiting. Copying isn’t just something that retailers have to worry about: The U.S. Defense Department has already had problems with (normally manufactured) counterfeit parts that can compromise military equipment and endanger soldiers, as CNN reported. There’s a fear 3-D printing could make it easier for flawed parts to enter the supply chain, or allow other governments to replicate U.S. military technology -- say, from a crashed drone, helicopter or plane. Campbell is researching ways to combat counterfeiting by introducing nanoscale materials, detectable only with the right tools, into 3-D printed parts to distinguish officially printed components from fraudulent ones.

“Make the part itself the anti-counterfeiting device,” Campbell said. But you can’t assume that a single solution will work forever, he indicated: “The turnaround time between when you develop an anti-counterfeit device to someone faking that device itself is anywhere from six to 18 months. People who do that kind of work are very clever.”

Right now, news headlines are primarily centered on the security risk posed by printed guns. The Liberator, a fabricated plastic gun made by the Austin, Texas-based group Defense Distributed, made its debut this month, but engineers say it’s likely more to be a danger to those who shoot it than to those they’re shooting at.

Defense Distributed founder Cody Wilson, who demonstrated the gun’s firepower in a video on YouTube, “could have blown his hand off,” Campbell said. “The bore through which the bullet egresses has to be a high-strength metal, and at this point we can’t make that with a 3-D printing machine. There’s a significant risk that the gun could just blow up.”

When Technology Surpasses Regulatory Precedents

Some lawmakers aren’t waiting for printed guns to improve before acting. U.S. Sen. Charles E. Schumer, D-N.Y., has called for legislation banning 3-D printed guns, noting that such weapons can bypass metal detectors. California state Sen. Leland Yee, D-8th District, has also called for new laws.

“We’re not particularly interested in regulating printers; we’re interesting in regulating the firearms that they make,” Dan Lieberman, Yee’s press secretary, said in a phone interview.

Yee’s team is still working on language for a legislative proposal -- one of the challenges is settling on the precise legal term that explains the function of a 3-D printer, according to Lieberman.

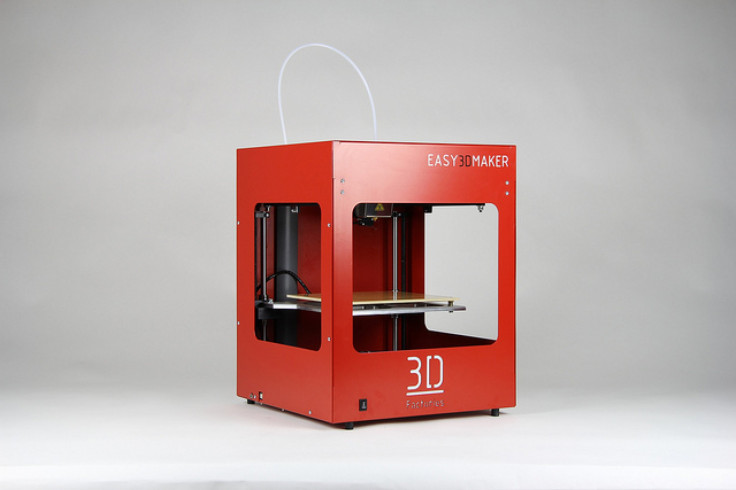

Defining exactly what 3-D printers do is, indeed, hard to do with exact precision, because it is such a comparatively new and fast-evolving technology. What a 3-D printer can do today is likely very different than what it can do tomorrow. While most commercial 3-D printers work with plastic “inks,” there are some people who envision devices that will work with materials of an entirely different nature.

University of Glasgow chemist Leroy (Lee) Cronin foresees a different kind of 3-D printer than the ones turning out bright plastic toys and honeycomb bracelets. He’s working on a so-called chemputer that would use chemical inks to assemble a chemistry set similar to those found in professional labs, as he and his fellow researchers noted in a paper published by Nature Chemistry.

In a June 2012 TED talk, Cronin extolled the potential boons of chemputing: being able to print new drugs quickly, should a superbug arise; being able to print drugs directly where they’re needed; using 3-D printing to create drugs personalized to your own DNA sequence. But the ability to print drugs on demand necessarily raises the prospect that people might print out recreational drugs -- or worse. The formula for cocaine isn’t exactly a trade secret. Nor is the formula for chlorine gas, a crude chemical weapon used by Germans in World War I and Iraqi insurgents in the mid-2000s.

“I’m not saying it’s going to happen tomorrow, or weeks or years from now, but there will be an increased capability for a small organization to create sophisticated biological or chemical weaponry,” Connor M. McNulty, who co-authored a paper on 3-D printing security concerns with Campbell for the National Defense University, said in a phone interview.

Representatives of both California’s Yee and U.S. Rep. Steve Israel, D-N.Y. -- who, like Empire State colleague Schumer, has also called for tighter restrictions on 3-D printed guns -- say their focus is on firearms for now.

While individual politicians might say they’re focusing on the product and not on the manufacturing device, there are some rumblings in Washington of the possibility of registering 3-D printers and restricting the dissemination of blueprints. This month, the U.S. State Department asked Defense Distributed’s Wilson to take down his blueprints for the Liberator, on the grounds that it wants to see if the files comply with international arms-export regulations. In an interview with Forbes, Wilson compared his case with that of Philip Zimmerman, who attracted government attention in the 1990s after he put his military-grade cryptographic software online.

Meanwhile, industry consultant Terry Wohlers said there are discussions going on right now at the U.S. Commerce and Defense departments with the registration of 3-D printers on the table.

“It’s definitely a knee-jerk reaction in Washington to regulate 3-D printers,” Wohlers said. “It’s only going to cut our own throats.”

Wohlers said he has mixed feelings about 3-D printed gun parts, but he pointed out the plans are already out there online. It’s virtually impossible to put the digital genie back in the bottle. And while the U.S. can implement all the regulations it wants, the industry is growing globally.

“The whole idea of regulating 3-D printing is enormously difficult to conceptualize,” Darren S. Cahr, an intellectual-property attorney with Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP, said in a phone interview. “Not to say that people haven’t tried. But people have been using injection molding, or tools and dyes, to make things for decades -- and centuries in some cases. It’s just not feasible to try and regulate everyone out there who can use a manufacturing process to make something.”

Just how radical are 3-D printers? Do they really require a suite of new laws? While a person might be able to someday print anthrax, or a bomb, or a batch of methamphetamine, you can already make those things with much lower-tech methods. You can find anthrax spores in soil if you look in the right place; pressure cookers were used to kill and maim at the Boston Marathon last month; and while cooking meth can be quite dangerous, it doesn’t require too many exotic ingredients beyond lye and Sudafed.

The case of meth may offer an instructive model. The trend of using decongestants to synthesize meth prompted Congress to pass a law in 2005 putting identification checks, purchase limits and other restrictions in place for Sudafed and similar drugs. And last year, one manufacturer, Acura Pharmaceuticals Inc. (NASDAQ:ACUR), released a formulation of nasal decongestant called Nexafed designed to thwart attempts to turn it into meth: When mixed with the ingredients commonly used to cook the drug, Nexafed turns into a useless gel. As 3-D printing becomes commonplace, the government and manufacturers may each play a role in oversight.

“It’s really hard to grasp what one or two regulations are needed,” 3-D printing security analyst McNulty said. “My biggest concern would be if we used these concerns as justification not to invest in the continued exploration and development of this technology.”

Global Competition And National Security Concerns

Other countries are still leagues behind America in 3-D printing, but the industry is starting to heat up around the globe. The U.S. head start in 3-D printing may not last for very long, and additive manufacturing, like traditional manufacturing, might be destined to move abroad. Last month, the Economist reported on the rise of both industry and hobbyist additive manufacturing in China. Singapore’s finance minister said in a February budget speech that the country’s government will invest $500 million over the next five years in support of advanced manufacturing techniques, including 3-D printing. America may not want to rest on its laurels.

“We’ve already lost our edge in wireless technology and flat-panel displays,” Campbell said. “We may be compromised on national security as a consequence if we’re not leaders anymore.”

Back on the home front, the domestic boom in 3-D printing means there’s some big unanswered legal questions brewing. Most notably: If someone shoots a someone else with a 3-D printed gun, or prints a chemical weapon, or copies a Prada handbag with a fabricator, can the manufacturer be held responsible?

Intellectual-property attorney Cahr pointed out that one of the factors courts use in establishing whether someone contributed to lawbreaking is foreseeability. The “nature” of the implement thus often comes into play.

For instance, if you lend a gun to someone and that gun was used in a murder, the victim’s family would probably have a much better case against you than if you lent a screwdriver to your neighbor, thinking he was going to work on his motorcycle, but he instead stabbed someone with it.

With 3-D printers, “this is a situation where there are a ton of completely legitimate uses for [the product],” Cahr said.

Firearm manufacturers are protected from civil lawsuits in federal or state court (except for actions brought over defective guns) by the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, a significant piece of pro-gun legislation enacted in 2005. It’s unclear whether a 3-D printer manufacturer could fall under the same shield -- there hasn’t been a major court case yet to set a precedent. But it’s not too early for people to begin mulling these legal issues. “It’s important for people to start engaging with it and thinking about it,” Cahr said.

‘The Cat Is Out Of The Bag’

Meanwhile, the industry seems to be erring on the side of caution. Shortly after the mass shooting at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., last December, Brooklyn, N.Y.-based Makerbot Industries LLC started culling gun-part blueprints from its Thingiverse catalog of user-uploaded designs. One design that’s no longer available is a five-round magazine for an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle. However, you can still download and print a fake gun modeled after a design in a “Star Wars” cartoon.

When asked about the possibility of people uploading bioprinting designs to Thingiverse, Makerbot representative Jenifer Howard said via email that MakerBot printers work with plastic, “so I don’t think our materials capability would be compatible with” chemical blueprints. Howard also pointed out that in addition to prohibiting designs that “[contribute] to the creation of weapons,” MakerBot’s terms of service for Thingiverse also prohibit users from uploading a schematic that “promotes illegal activities ... or is otherwise objectionable.”

In a 2011 blog post ---- which appears to have been deleted, but which is still available as an archived page -- MakerBot CEO and founder Bre Pettis wrote about his personal conflict over 3-D printed weapons. Pettis said he enjoys shooting at tin cans, but had a childhood friend commit suicide with an improperly registered gun.

“I’m not convinced that 3-D printing is easier than buying a gun illegally, but it does offer another avenue for weapons to enter the world,” Pettis wrote. “One thing that’s for sure, the cat is out of the bag and that cat can be armed with guns made with printed parts.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.