9,000-Year-Old Caribou Hunting Site Under Lake Huron Reveals ‘Complex’ Strategies Of Ancient Big Game Hunters

The ruins of a 9,000-year-old caribou hunting site on the bottom of one of the Great Lakes is providing clues about the mysterious lives of North America’s first inhabitants

Researchers from the University of Michigan announced Monday that an elaborate collection of stone walls and V-shaped structures was discovered deep beneath the surface of Lake Huron. Two parallel lines of stones were arranged to make a 26-foot-wide and 98-foot-long lane that ends in a natural cul-de-sac. Researchers also found evidence of hunting blinds -- covered structures meant to conceal hunters -- built along the lane.

The relics are thought to have helped ancient paleo-Indians, big game hunters who crossed the Bering Strait into North America during the last ice age, corral caribou herds migrating across what was then a dry land-corridor connecting northeast Michigan with southern Ontario. The structure would have funneled caribou traveling along their natural migration path into an enclosure where they could be killed.

Details of the discovery are described in a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science Early Edition. Researchers say the ancient hunting site is the most sophisticated ancient structure unearthed in that region.

"It's just way more complex than anything we've seen before," John O'Shea, a University of Michigan archeologist and author of the study, told The Vancouver Sun.

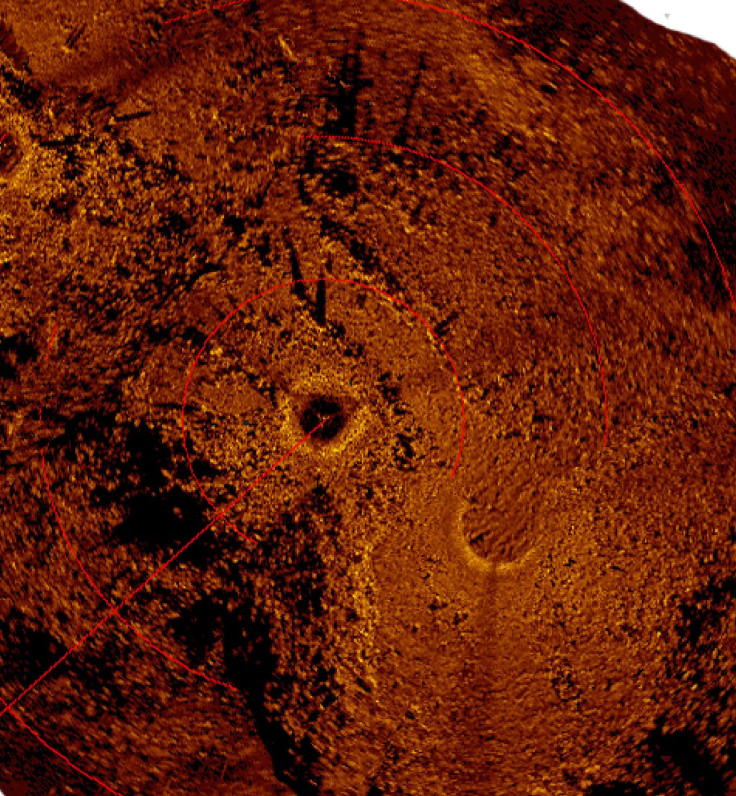

O’Shea said the hunting site was actually found by accident. Researchers using scanning sonar to map the features on the bottom of Lake Huron noticed an odd arrangement of unnatural structures.

To explore the site deep below the lake’s surface, researchers used a camera mounted to a remotely operated vehicle. Scuba divers were later sent to investigate the site even closer. They unearthed 11 chipped stone flakes -- probably used to repair stone tools -- near the hunting lane, providing further evidence of the presence of an ancient hunting location.

"The fact that all of the migrations tend to converge on these two locations ... would have provided predictability for ancient hunters, which is why we see so many structures located in these spots," O'Shea told Live Science.

Researchers say the discovery highlights the paleo-Indians temporal hunting patterns; small hunts in the fall, followed by a large caribou hunt in the spring.

"The larger size and multiple parts of the complex drive lanes would have necessitated a larger cooperating group of individuals involved in the hunt," O’Shea said in a statement. "The smaller V-shaped hunting blinds could be operated by very small family groups relying on the natural shape of the landform to channel caribou toward them."

O’Shea said similar ancient hunting structures could still be out there. His team plans to continue mapping the floor of Lake Huron to see if they can uncover anything else.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.