After Charlie Hebdo Attack, Muslim Scholars Explain Role Of Satire For European Muslims

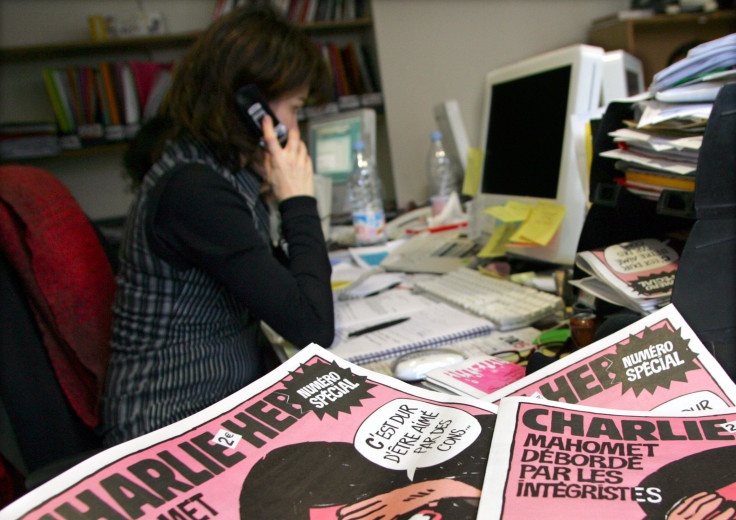

Charlie Hebdo, the satirical newspaper attacked by Islamic terrorists on Wednesday in Paris, has a long history of mocking every facet of French society. Politicians, bankers, capitalism, Judaism and Christianity have all been targeted by the publication in a tradition that dates back to scandal sheets on Marie Antoinette before the French Revolution.

As part of French society, Muslims are open to criticism just like any other group Charlie Hebdo satirizes. So why are some French Muslims particularly offended by the magazine's images of Prophet Muhammad?

“Muslims in Europe are one of the youngest and most recent minorities, so it is not surprising that they are particular alert to episodes of real or perceived racism and stigmatization,” Sara Silvestri, senior lecturer at City University London, who specializes in Islamism, religion and politics, said. “They are still in the process of protecting their corner and identity in European societies and for this reason are perhaps more sensitive to satire.”

Indeed, studies show that European Muslim immigrants face discrimination. France is home to the largest Muslim population in Europe, with 7.5 percent of the country’s population identifying with the religion in a 2010 survey. Reports have shown Muslim immigrants in France are poorly integrated into society. They have lower incomes, face negative stereotypes and, at times, they face violence. French society’s emphasis on secularism doesn’t help. Full veils are banned in public places. All religious symbols, including hijabs, are prohibited in public schools as well. And more young French Muslims become radicalized than young Muslims in other European countries.

“I think every religious tradition is vulnerable to satire, especially in secular societies,” Ali Asani, director of the Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Islamic Studies Program at Harvard University, said. “In France, where religion is seen as something backward, I think the issue here is larger, because it’s the resort to violence to address the offense.”

While it is not written in the Quran, the hadith, or oral tradition, says not to transform the Prophet Muhammad into a symbol of worship. For this reason, certain depictions of the Prophet are considered blasphemous. But Muslim academics agree that the Charlie Hebdo cartoons are more offensive than sacrilegious.

“The problem ... in the cartoons is not the fact they are blasphemous from a strictly Islamic point of view,” Dr. Hatem Bazian, professor of Middle Eastern studies and ethnic studies at the University of California, Berkeley, and cofounder of Zaytuna College in California, said. “Rather they are to be understood as racist and bigoted discourse directed at members of the Muslim community and constituting it as the basis for their belonging or membership in the society.”

The Charlie Hebdo attack reminded Fatih Alev, the chairman of the Danish Islamic Center in Copenhagen, of similar incidents in his country. In 2005, satirical cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, including one that depicts him as a terrorist, were published in Danish and Norwegian newspapers. Protests ensued and xenophobic sentiment spread across secular Denmark. In 2010, Danish authorities thwarted a terrorist plot to attack the offices of Jyllands-Posten, the newspaper that published the cartoons in Denmark.

“I think it’s not about religious sentiment but cultural ways of perceiving satire,” Alev said. “Though I am very religious person, I was not offended [by the 2006 cartoons]. Why? Because I was used to the Danish way of debating,” Alev said. “For Muslims in Denmark who were not used to Danish debate, it was a shock. They were very offended. They didn’t understand what was going on.”

But the Charlie Hebdo attack and other incidents also have to do with a rift within Islam, not just between some Muslims and the Western societies in which they live. There is a struggle, Asani said, between two conflicting ideologies in Islam: the theology of love and the theology of power. The former can be seen in a traditional story of the Prophet Muhammad who, rather than condemn a woman who would throw trash at him every day, ignored her -- and later even gave her food and took care of her when she fell ill.

“That is one model of responding to things like this,” Asani said, referring to the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. "It's one interpretation of Islam that responds [to such acts] with love and compassion."

And the theology of power stems from the political context Muslim societies found themselves in during the 18th and 19th centuries, when they were colonized by European powers.

“In a sense, if you have power in this world, God is on your side. You are part of the righteous,” Asani said. “Those we identify as jihadi and Islamist follow the interpretation that promotes the theology of power, and a natural consequence is the use of violence.”

It’s this violence that has led Muslim leaders, organizations and individuals to express condemnation for the attack, saying that Islam is a “religion of peace and non-violence.”

Asani disagreed.

“Islam is a concept and it can be used to promote peace or used to promote violence. It’s how people interpret it,” he said. “It’s people who are peaceful or violent, that’s what all of this comes down to.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.