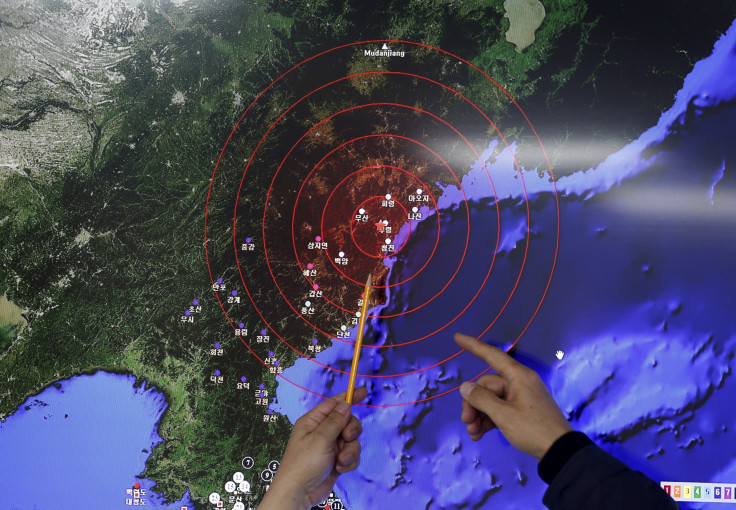

After North Korea Hydrogen Bomb Test, China, Japan, East Asia Security Threats Come Into Focus

The geopolitical ripple effect from North Korea’s apparent first hydrogen bomb test Tuesday night has already threatened to dramatically alter the fragile security situation in East Asia, with the epicenter of outrage firmly fixed on Pyongyang’s regional rivals Japan and South Korea. While diplomats in Tokyo and Seoul condemned the thermonuclear blast and called for tougher United Nations sanctions, the biggest denouncement came from North Korea’s ally China, which expressed grave concern over possible fallout in areas bordering North Korea.

However, while China might agree to additional economic and import sanctions against North Korea, it is unlikely to enforce them and will not change its security posture with the hermit kingdom given how useful Pyongyang has been as a buffer between the U.S.-militarized South Korea, according to expert analysis.

“I don’t think it will change the security situation in the region too much, but it will put pressure on China and the U.S. and South Korea to find a better way to stop the nuclear program or at least slow it down,” said Lisa Collins, a fellow with the Korea Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. “But it certainly won’t change China’s security calculus about its relationship with North Korea. China will make a cost benefit analysis and right now North Korea is still much more of a benefit to them and less of a burden in terms of damaging and being a danger to their core interests.”

Even before North Korea purportedly tested a hydrogen bomb, its relations with China had been souring for years over Pyongyang’s belligerence toward security in the region. North Korea has consistently threatened war with South Korea while also drawing ire from the U.S., which has more than 28,000 troops based in the democratic country. Last August, North Korea ordered its troops to adopt a warlike state after an exchange of fire between with the South. This came just one week after a land mine placed inside the Demilitarized Zone maimed two South Korean soldiers. Seoul reacted by placing huge speakers on the border that blasted propaganda into the North.

North Korea's nuclear explosions compared pic.twitter.com/gfrA9G6jcg

— Agence France-Presse (@AFP) January 6, 2016Despite this and China’s outrage over the blast, Kim Jong Un's regime will likely continue to act with impunity, according to Hazel Smith, director of the International Institute of Korean Studies at Britain’s University of Central Lancashire.

“Every nuclear test that they’ve had has caused massive consternation in China. But the North Koreans have never been susceptible to letting China tell them what to do,” Smith told the Guardian Wednesday.

While a unified Korea would help end the political turmoil on Beijing’s front door, North Korea has acted as a useful buffer zone that keeps South Korea and the U.S. away from its borders and prevents any potential refugee crisis in the event of an internal North Korean collapse, said Collins, who also noted that North Korea acts as a useful regional distraction that allows Beijing to build a sphere of influence in the region.

Over the last year, China built artificial islands in the South China Sea in an attempt to gain sovereignty over the entire region and the energy reserves that are thought to exist under the ocean floor. But it also built the islands in order to give its military extended range. On Wednesday, China landed an aircraft on one of the islands to prove the functionality of the 3,000 meter (10,000 feet) runway on Fiery Cross, which was once a small reef that barely peaked above the surface of the sea. Regional rivals along with the U.S. had contested China’s sovereignty in the region.

The idea of stronger U.N. sanctions against North Korea was proposed by South Korea and Japan just hours after the explosive test took place, but chances are Beijing will not follow through with them, said Collins, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies. U.N. sanctions against North Korea, which were first implemented in 2006, target the finances of government officials and prohibit the country from bringing in weapons and foreign goods, according to a Treasury report.

This will likely be frustrating for Japan and South Korea, who are both desperate to ensure that Pyongyang’s nuclear program is dismantled quickly. North Korean ballistic missiles could easily reach either Tokyo or Seoul, although it’s not yet known if the missiles and warheads are reliable or technologically advanced enough to work together.

“I do think that when sanctions are implemented in a comprehensive and unilateral way as we saw with Iran they can be more effective, but unfortunately sanctions against North Korea have been ineffective because of China’s lack of implementation,” said Collins, who also noted that a regional conflict was highly unlikely.

“Given that, Japan and South Korea have limited options,” she added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.