AG Holder Defends Embattled Voting Rights Act

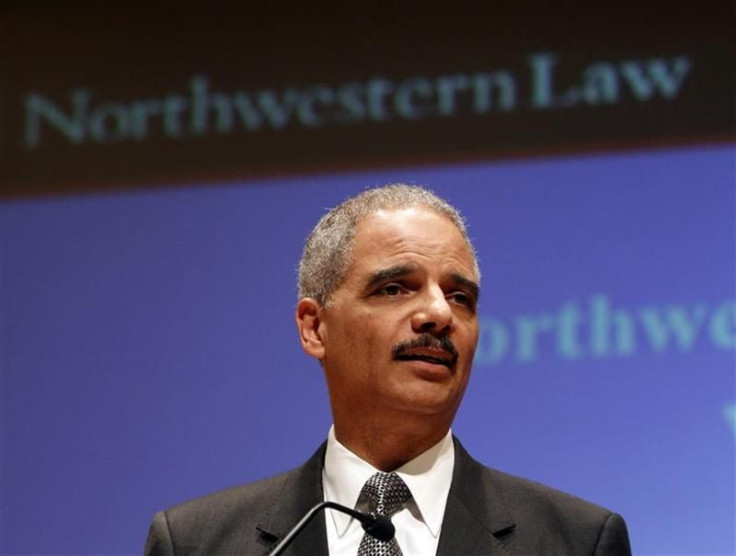

With a crucial portion of the 1965 Voting Rights Act under fire from Republican lawmakers and conservative justices on the Supreme Court, Attorney General Eric Holder defended on Wednesday the historic law as a necessary tool to combat discrimination at the polls.

In a speech to the American Law Institute, Holder rebutted criticism that the provision requiring southern states of the Old Confederacy to pre-clear any changes to voting law or electoral districts with Washington is an outdated relic from a time before civil rights laws.

Each of these challenges to Section 5 claims that we've attained a new era of electoral equality, that America in 2012 has moved beyond the challenges of 1965, and that Section 5 is no longer necessary, Holder said, according to prepared remarks. I wish this were the case.

The Justice Department under Holder has used Section 5 to block states from enacting new political maps and voter identification laws that the agency says disproportionately affect minority voters.

When a jurisdiction fails to meet its burden of proving that a proposed voting change would not have a racially discriminatory effect, we will object, as we have in 15 separate cases since last September, Holder said.

The Voting Rights Act has enjoyed the support of Democrats and Republicans -- in 2006, President George W. Bush, a Republican, reauthorized the law for 25 years, saying we've made progress toward equality, yet the work for a more perfect union is never ending.

For his successor, President Barack Obama, a Democrat, the Voting Rights Act has become a political battle in Congress and the courts, where Section 5 could be struck down at the Supreme Court before lawmakers get a chance to do so in 2031.

The Justice Department has used its pre-clearance power to prevent Texas and South Carolina from going forward with a new electoral map the agency says fails to account for the state's black and Hispanic population boom. Meanwhile, Texas and South Carolina were blocked from enacting a voter identification law -- the kind the Bush Justice Department had supported when Georgia passed its regulations.

These initiatives are the result of the Republican takeover of statehouses around the country after the 2010 midterm elections, putting the GOP in control of the once-a-decade redistricting process and giving the party power to move legislation.

The legal fights between the Obama Justice Department and Republican-dominated states have sparked calls among conservatives to end Section 5 pre-clearance, arguing it is an antiquated rule for southern states that have long shed their reputation for violently barring black voters from the polls.

Rep. Paul Broun, a Georgia Republican, recently tried to block the Justice Department from enforcing Section 5 with a late-night amendment to a spending bill. He called Section 5 an onerous burden on southern states, requiring them to jump through a bunch of hoops to enact voter ID laws others are free to enforce.

Broun pulled the amendment after he was denounced on the House floor by his fellow Georgian, Rep. John Lewis, a Democrat and civil rights leader in the 1960s.

But for those who want to see Section 5 gone, perhaps some patience is all that is needed. The Supreme Court seems poised to strike down the pre-clearance provision of the landmark voting law.

The justices have avoided the constitutional question over Section 5 so far, but they are now squarely before us, judges on the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit wrote, setting up a Supreme Court battle over race and civil rights.

The appellate judges Friday decided Congress was within its right to continue requiring states to clear election law changes.

Congress' finding that Section 5 has a deterrent effect rests on evidence of current and widespread voting discrimination, as well as on testimony indicating that section 5's mere existence prompts state and local legislators to conform their conduct to the law.

Alabama's Shelby County, which argued in the suit that Congress overstepped its authority when it reauthorized the Voting Rights Act in 2006, is expected to appeal to the Supreme Court, where some of the conservative justices are itching to strike it down as an unconstitutional intrusion on state sovereignty.

When Texas defended its political maps before the Supreme Court, Justice Clarence Thomas in January took the opportunity to reiterate his opposition to pre-clearance. In a 2009 opinion, Thomas said southern states and the handful of localities covered under Section 5 are not now engaged in a systematic campaign to deny black citizens access to the ballot through intimidation and violence.

Similarly, Chief Justice John Roberts in 2009 also noted how voter turnout and registration in the South is near parity and that there are only rare instances of blatant discrimination.

These improvements are no doubt due in significant part to the Voting Rights Act itself, and stand as a monument to its success, Roberts wrote. Past success alone, however, is not adequate justification to retain the pre-clearance requirements.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.