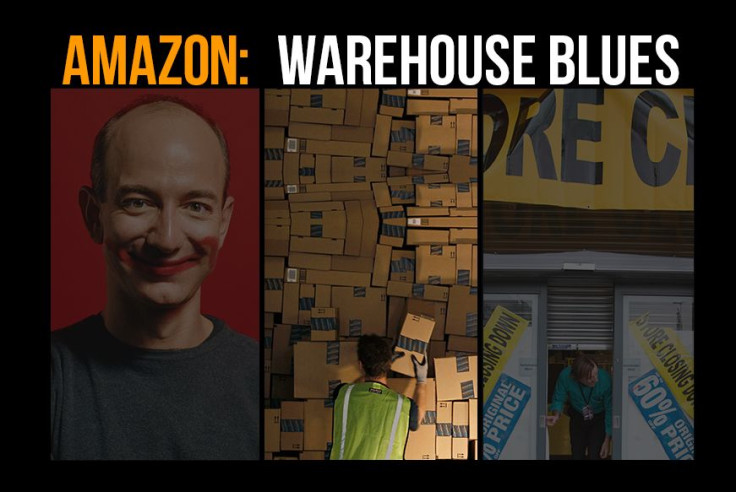

Amazon.com's Workers Are Low-Paid, Overworked And Unhappy; Is This The New Employee Model For The Internet Age?

This is the second of a three-part series exploring Amazon’s business model. On Wednesday, we examined the company's lack of profitability relative to its revenue growth. Today, we probe the company’s labor practices. On Friday, we'll look at the company's impact on small retailers.

NOTE: This story has been updated to include Amazon.com's remarks regarding its temporary workers and its denial of allegations regarding the way productivity goals are measured in its warehouses.

It’s easy to miss Amazon.com’s 600,000-square-foot warehouse in Breinigsville, Pa., while traveling along U.S. Route 222. It’s one of several large, nondescript concrete boxes in the Liberty Business Center a mile south of Interstate 78, an ideal location for shipping tons of merchandise every day to customers in the northeastern United States.

Inside one of two warehouses Amazon has at the industrial park, a mix of about 1,600 full-time, part-time and temporary workers receive, sort, pick and ship thousands of packages per shift. Recently, they began seasonal mandatory overtime of five 11-hour shifts per week to meet the demand from online holiday shoppers. That pace will continue through the new year before workweeks are dropped back to four 10-hour days per week. After the holidays, hundreds of temporary employees at the facility will return to the ranks of the unemployed.

Warehouse work isn’t easy in the best conditions, but in recent years the No. 1 e-tailer has found itself in the spotlight over its treatment of workers at facilities such as the one in Breinigsville -- a spotlight usually reserved for companies like Wal-Mart Stores Inc. (NYSE:WMT), which are favorite targets of labor rights advocates. And increasingly, workers are coming forward to discuss the work culture at the world’s largest online retailer. “Amazon’s employees are viewed as a necessary evil. If they could get machines to do this work they would,” Neal Heimbach, who has worked for Amazon in Breinigsville since August 2011, said. “Amazon is not happy with 100 percent productivity from its workers. One hundred percent to them is, 'Well, at least you’re doing your job.’”

Eastern Pennsylvania’s unemployment and underemployment rate remains above the national and state averages, which means fewer job options for people like Heimbach. Lehigh Valley, which includes Allentown, Bethlehem and Easton, as well as many smaller nearby communities such as Trexlertown and Breinigsville, has never really returned to its economic heyday when well-paying, secure jobs were plentiful in mining, steel, rail and textiles, a situation famously chronicled in the song “Allentown” by recording artist Billy Joel in 1982. In 2009, Allentown lost its last major manufacturer, Mack Trucks Inc., when the Volvo subsidiary relocated to Greensboro, S.C., taking with it 600 jobs.

But the region’s shedding of decent jobs has been a human resources goldmine for warehousing and distribution companies, and Amazon.com Inc. (NASDAQ: AMZN) has certainly dived right in; Pennsylvania joins Kentucky and Indiana in having the highest concentration of the company’s fulfillment centers.

Amazon warehouse employees typically have few choices but to work for $9 to $14 per hour, a base rate that locals say is typically higher than what other, smaller warehousing operations pay in the area. But in return, they endure physically demanding conditions under constant surveillance and an unforgiving computer-based system demerit program, with zero job security.

Mary Osako, an Amazon spokeswoman, said the company’s wages for these workers are 30 percent higher than people who work in “traditional retail stores."

“And that doesn't even include the stock grants that full-time employees receive,” she added. “We also offer full-time benefits including healthcare.”

Amazon warehouse employees (or, as the company calls them, “fulfillment center associates”) contend they’re told by Amazon and outsourced managers to meet productivity goals designed to be unattainable for most in an effort to keep them in a perpetual state of insecurity about their continued employment. If they give up or are fired, there’s a legion of temp workers -- recruited by subcontracted labor recruiters who have offices inside the warehouse facility -- waiting to take their turn processing hundreds of packages per hour.

Employee vs. Employer

Amazon, founded in 1994 as a fledgling online book retailer in the earliest days of the Internet, has only in the past few years become the target of labor-abuse allegations, most recently this year with several U.S.-based lawsuits in five states, including one brought by Heimbach in Pennsylvania. Chief among the complaints, which could soon be consolidated into a nationwide class action lawsuit, is the allegation that Amazon.com fails to compensate hourly workers for time spent waiting in airport-like security lines each time they exit the warehouse. Aimed at combatting product theft, this process can take up to 20 minutes.

The suits also contend that while employees get a strictly regimented 30-minute unpaid lunch break, much of that time can be taken up walking from one end of the warehouse to the other. The lawsuits also claim the company is so radically fastidious with workers’ time that it requires employees to count the start and end of their two paid 15-minute breaks per shift from their work stations.

“If it takes three minutes from the moment the bell rings to get to the break room, now you've only got 12 minutes left to rest. But then you have to use three minutes to get back to your work area before the next bell rings, so your break is really nine minutes,” Heimbach told International Business Times. “And they constantly monitor you with supervisors that look at computer screens.”

The complaints allege that if Amazon had to include these tiny increments of time, many workers would top the 40-hour workweek, which would make them eligible for overtime.

Heimbach’s suit asks for at least $50,000 to compensate employees at the warehouse. In its latest earnings report outlining future risks, Amazon said: “We dispute the allegations of wrongdoing and intend to vigorously defend ourselves in these matters.”

‘Management By Stress’

A 2011 exposé by Pennsylvania’s Morning Call newspaper chronicled the plight of Amazon warehouse employees in Breinigsville. According to that article, Amazon hires were forced to work in dangerous summertime heat conditions, temps as high as 110 degrees. In fact, so many workers ended up in the local hospital that an attending physician reported the case to federal workplace safety regulators. In the wake of the Morning Call investigation, Amazon spent $52 million to install cooling systems in its warehouses.

But apparently the company hasn't lowered the heat on the productivity requirements it sets for employees, goals that are well beyond the industry norm for other warehouse and shipping companies.

A source who went undercover at an Amazon sorting center in California for eight weeks this summer as part of academic research into warehouse working conditions told IBTimes that Amazon wanted its employees to pack about 240 boxes per hour. A floor manager, with experience at multiple logistics firms, conceded to this source that the industry standard was only about 150. The source spoke only on condition of anonymity because his research is ongoing.

Amazon doesn’t publicly disclose the number of packages per hour its warehouse workers are expected to process, but Heimbach’s estimates matched what the source claimed: About 250 larger packages per hour and “nearly 500” for smaller packages such as books and CDs.

“If you’re 85 or 90 percent within their plan, you’re considered on the border,” Heimbach said. “The reality of it is they’re primarily concerned about getting product out the door at the fastest rate possible.”

Amazon spokesperson Osako said the claims that productivity goals are set to be unattainable for most warehouse employees are “simply inaccurate.”

Moreover, Amazon’s productivity numbers are apparently purposely designed to be unattainable for most workers so that the employees feel that they are falling down on the job and push harder to hit the impracticable levels. This strategy, known as management by stress, was described in the book “The New Ruthless Economy: Work and Power in the Digital Age,” by Simon Head, a fellow at the Rothermere American Institute at the U.K.’s Oxford University, as "one in which a significant minority of workers are operating at the margin of inefficiency, so that supervisors can bear down and get them to work faster.”

Indeed, the California undercover warehouse worker told IBTimes that his Amazon floor manager admitted to him that the packages-per-hour goals were set higher than was expected from them. This came up because the worker was able to pack only about 210 boxes per hour, above industry standards but below Amazon’s.

“[The floor manager] and I got friendly a little and he was willing to talk to me openly about these productivity goals,” the source told IBTimes in a recent telephone interview. “He was under the impression I was working my way through school. 'Don't worry,' he said. 'We're not going to fire you at 88 percent of 240.'”

Social pressure is added to the mix, in Amazon.com’s case by mingling temp employees with distinctively colored badges alongside a larger pool of direct hires, creating what Carole Cadwalladr, a reporter for the U.K.’s Guardian newspaper, called in a recent investigative piece about working conditions of Amazon warehouse employees in Britain, “a subtle apartheid at work” between temps and Amazon’s directly hired, better-paid workers who perform the same duties.

“There's the blue badge [denoting an Amazon direct-hire] versus the white badge [Amazon outsourced temp] and a very visible hierarchy at the warehouse,” said the source who worked undercover in California. “The blue badge gives you the potential to be hired full time and the competition between [temp] agency workers and direct hires is high.”

Says Amazon spokesperson Osako: "Seasonal temporary workers at the company’s warehouses earn 94 percent of the company’s starting wage for its permanent workers . . . In 2012, we converted thousands of seasonal associates into full-time employees.”

The Blue-State Wal-Mart

In July, U.S. President Barack Obama addressed the nation from inside Amazon’s 1.2 million-square-meter Chattanooga, Tenn., warehouse, where he pitched his ideas for tackling the growing problem of income disparity, lackluster postrecession jobs recovery and “what we need to do as a country to secure a better bargain for the middle class.”

Notably, the president has never shown up at a Wal-Mart Supercenter to talk about creating good middle class jobs, even though Arkansas-based Wal-Mart employs about 1.3 million people in the U.S. compared to Amazon’s 88,000 -- and many of the jobs at both companies offer comparable compensation.

Indeed, while Wal-Mart and the founding Walton family are consistently criticized by fair labor advocates for the way the world’s largest retailer treats its lowest-paid workers, Seattle-based Amazon and its Internet- and media-savvy CEO Jeff Bezos, who gets press for talking about delivering packages by robotic drones but not the company’s employment practices, appears to get a pass.

The difference between the two companies is visibility. Unlike Wal-Mart, Amazon has no retail outlets, and no underpaid workers clearing shopping carts in parking lots with whom to avoid eye contact as you enter the big-box outlet. Amazon customers have no interactions with Amazon employees; they work behind the scenes. And there aren’t any websites ridiculing Amazon customers.

People who order products from Amazon see only a massive online catalog with the company’s smiley face logo, a virtual shopping cart and a button that says “Proceed to Checkout.” After a few mouse clicks, within 48 hours packages appear with remarkable reliability at their homes or workplaces.

And if these customers happen to drive past a big white concrete building on the side of the highway filled with workers pushed to their limits who were responsible for the on time shipment, they probably won’t even know it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.