Amid Freddie Gray Trial, What Would Prison For William Porter Look Like? Ex-Baltimore Officer Could Go In Protective Custody For Safety

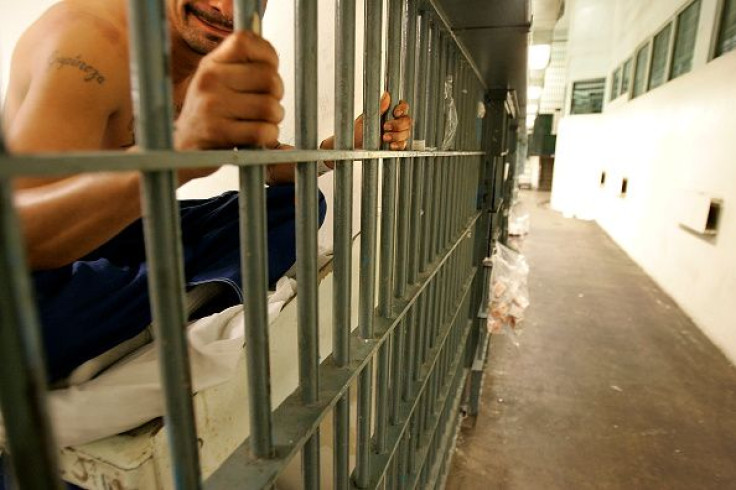

William Porter, one of the six Baltimore police officers charged in the death of Freddie Gray, continued waiting Tuesday to learn whether a jury will send him to prison on one or all charges of involuntary manslaughter, second-degree assault, misconduct in office and reckless endangerment. If Porter were convicted and later sentenced, he would likely find himself at odds with other inmates, creating significant safety concerns.

With the recent rape conviction of a former Oklahoma City police officer and a verdict for Porter likely coming soon, increased attention is being paid to police finding themselves on the other side of the law. While convicted former members of law enforcement are usually placed in protective custody, that same isolation also limits their chances of participating in activities meant to make life behind bars more bearable, legal experts said, underscoring the fact that prison life for Porter could look much different from that of his fellow inmates.

“It's case-specific, but generally the officer is going to be put away from the general population, and the reason for that is it is a safety issue,” said Thomas Maronick, a Baltimore defense attorney who has represented police officers in criminal cases.

Police officers behind bars are the frequent target of gangs, which in Baltimore have proved to have massive sway while incarcerated. One gang, the Black Guerrilla Family, essentially took over operations of the Baltimore City Detention Center over the last decade, smuggling drugs and forcing the jail to close this year, the Baltimore Sun reported.

The gangs, said Maronick, know that hurting or killing a cop sends a definitive message evoking fear and respect from other inmates, as well as a sense of revenge.

Freddie Gray case: Closing arguments in William Porter trial done; jury deliberations next https://t.co/I4mK2UJKWN

— CNN Breaking News (@cnnbrk) December 14, 2015

“They figure they were wronged by the police at some point in their life, and think they can settle the score [by hurting an officer],” Maronick said.

The bounty convicted police officers have on their heads in prison has led to them being routinely placed in protective custody, secluded in cells and segregated from the general population — treatment reserved for high-value inmates, including those set to testify in other cases, Maronick said. Depending on the threat level, former police personnel could stay in these cells for anywhere from a couple days to nearly their entire stay.

“The prison says, ‘The only way we can protect you if you feel like you are at risk from other inmates is to put you in a small cell, and limit the number who has access to you,’ ” said Andrew Levy, a Maryland defense attorney and adjunct professor at the University of Maryland law school.

Prisons tend to err on the side of caution when it comes to keeping officers away from other inmates. If a former member of law enforcement is killed while in the general prison population, that could lead to a lawsuit where the family of the dead could claim something should have been done to protect the officer given his prior occupation, Maronick said.

Porter’s is just the latest in a string of cases involving law enforcement personnel. He is one of six officers charged in Gray’s death, which led to rioting in the streets of Baltimore and further scrutiny of how police use force on suspects. Gray, a 25-year-old African-American, was arrested April 12 for possession of what police said was an illegal switchblade. While being transported in a police van he fell into a coma. He died April 19, his death ascribed to spinal cord injuries.

In the case of Daniel Holtzclaw, the former Oklahoma City police officer, prosecutors said he used the power of his uniform to sexually assault 13 African-American women who ranged from 17 to 57 years old. It was said at his trial that he preyed on women he didn’t think anyone would believe if they said he raped them.

The prison cells for inmates in protective custody are not particularly nicer or worse than those in the general population, they are simply separate. Along with the highly secure housing comes a limitation of what the inmates are allowed to participate in. Because recreational and eating time lend themselves to a higher risk of being hurt, those in protective custody generally do not partake in them with other inmates.

“By its nature it limits the opportunities available to an inmate,” Levy said. “There’s a disincentive to requesting protection.”

Freddie Gray injured in 'casket on wheels,' prosecutor says of Officer William Porter trial https://t.co/PgL0prIQpE pic.twitter.com/vlBCBOgmnr

— People magazine (@people) December 15, 2015

In most prisons, despite what many people think, there’s a fair amount of freedom of movement. If an inmate is segregated, his or her freedom of movement is greatly diminished, said Levy.

Police officers aren’t identified by their profession in federal prison. They are thrown in with the rest of the convicts and are removed only if there is a significant danger presented, Edmund Ross, Federal Bureau of Prisons spokesman, said. Individual prisons have files denoting whether an inmate was an officer or not, but the Federal Bureau of Prisons doesn’t track how many officers are incarcerated across the country.

“We provide a safe and secure professional environment for all inmates regardless,” Ross said.

The Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services, which operates Maryland state prisons, did not immediately return a request for comment.

If Porter is convicted on all four charges against him, the state will most likely want to send him to a prison farther inland, away from Baltimore, Maronick said. One of these could be the Maryland Correctional Training Center in Hagerstown, a prison that houses minimum- and medium-security prisoners as well as prerelease inmates.

Some 2,730 inmates can be housed in the facility, and at which prisoners can earn GEDs and pursue vocations such as repairing printers and copiers. Inmates at the facility are allowed visitors and can reportedly watch TV. While Maronick said Porter could go to the Hagerstown site, it is one of about 25 state prisons in Maryland. Either way, Maronick said, Porter could have the potential to be a valued target for other inmates.

“He’s definitely going to need some sort of protection, there’s just been too much coverage,” Maronick said. “I don’t think there will be a bounty on his head, but he would need protection.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.