Amnesia Breakthrough: Researchers Restore ‘Lost’ Memories In Mice Through Light

Amnesia -- a medical condition that results in loss of memory -- has long been a neurological puzzle. Scientists have often debated whether this condition, which can be caused by a brain injury, shock or illness such as Alzheimer’s disease, is irreversible, or whether memories are merely “blocked” and can somehow be restored.

Now, a study conducted jointly by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Japan’s Riken Brain Science Institute is providing new insights into the workings of amnesia. The study, published Friday in the journal Science, describes the use of a technology known as “optogenetics” to reactivate memories that could not otherwise be retrieved. These findings contradict the so-called “storage theory,” which posits that memory loss occurs when cells are damaged and memory cannot be stored.

“The majority of researchers have favored the storage theory, but we have shown in this paper that this majority theory is probably wrong,” Susumu Tonegawa, director of the Riken Institute, said, in a statement. “Amnesia is a problem of retrieval impairment.”

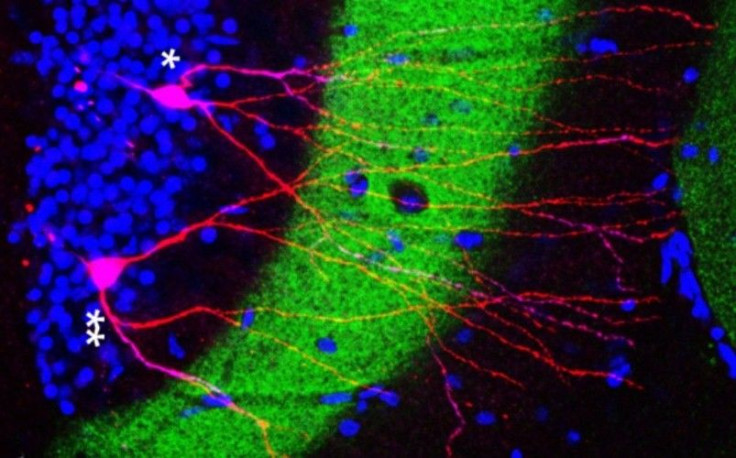

The study was conducted on mice, in which amnesia was induced through a chemical named anisomycin, which inhibits new protein synthesis and the strengthening of synapses important for memory encoding. Then, the researchers used blue-light pulses to stimulate “memory engrams,” which are the neurons that are activated when memories are formed. Upon stimulation, it was found that the mice were able to recall a memory -- which, in this case, was an electric shock before their induced retrograde amnesia -- that was believed to have been lost.

What this study shows is that memories are not stored in synapses of individual engram cells, but in a circuit composed of multiple groups of cells -- a finding that raises hopes for treatment of patients suffering from severe amnesia.

“We are proposing a new concept, in which there is an engram cell ensemble pathway, or circuit, for each memory,” Tonegawa said, in the statement. “This circuit encompasses multiple brain areas and the engram cell ensembles in these areas are connected specifically for a particular memory.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.