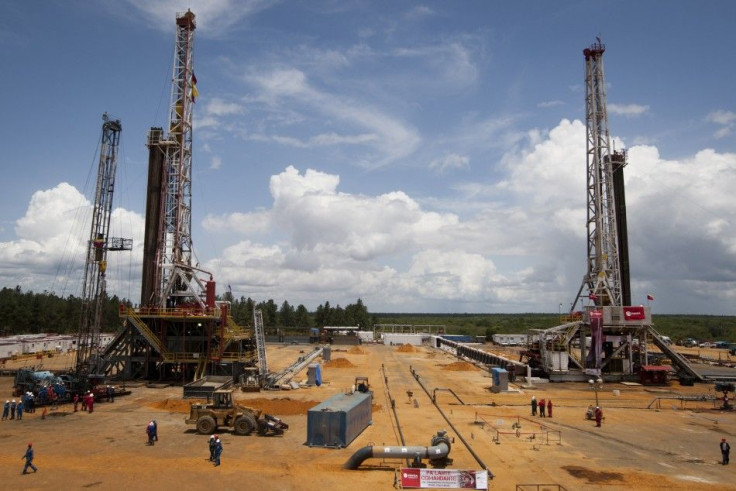

Analysis: What Will It Take To Restore Venezuela's Once Mighty Oil And Gas Business?

This week's death of Hugo Chavez, the socialist firebrand who ruled Venezuela for 14 years, could open the door for foreign oil companies to return to a nation whose petroleum business now operates far beneath its potential.

The possibility and pace of any such return will depend on one thing: how badly the government needs cash, which is something that is in increasingly short supply.

The reason for the shortage of money in this nation of some 30 million people is not difficult to understand. To fund social welfare programs, Chavez and his chavismo military government nationalized nearly 1,000 private companies and tapped the cash flow of the state-owned oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela SA (Pdvsa), rather than reinvest in the business. As a result of using its cash flow to build housing, subsidize goods and launch other vote-getting projects, equipment fell into disrepair, and workers became disgruntled with stagnant wages and worsening safety standards, especially at refineries. No other industry has come close to replacing Venezuela's energy business, so today Pdvsa provides the overwhelming majority of the country’s declining revenue.

The upshot of years of neglect and mismanagement has been a 20 percent drop in production: In 2000, oil production in Venezuela, which has the world’s largest crude oil reserves at nearly 300 billion barrels of oil, was about 3.16 million barrels per day; 11 years later, that number had fallen to 2.47 million barrels per day. By contrast, the U.S., with vastly smaller reserves, now produces more crude oil than Venezuela.

Analyst estimates of what Venezuela could produce, if its assets were properly managed, range from 6 to 9 million barrels per day.

Getting to that kind of output, even under the most favorable post-Chavez scenario, will require foreign energy and energy-related companies. And that means change will be slow and incremental, analysts say.

“We suspect that very little will change in the near term," said David Rees, emerging markets economist at London-based Capital Economics. "Mr. Chavez’s rule has become ingrained in the nation’s institutions and ruling elite, and their vested interests mean that there is little likelihood of any change. The government will keep monetary and fiscal policy loose ahead of any election. But unless the authorities can find some hard currency to fund an increase in imports to ease shortages of intermediate goods, stimulus measures are likely to simply stoke inflation and exacerbate strains in the balance of payments rather than drive faster economic growth.”

The need to solidify the ruling party's unity will likely delay until at least 2014 any serious attention to the economy.

“I don’t think much will change in the short to medium term, by which I mean basically this year,” Alejandro Velasco, assistant professor at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, said. “Some of it will be dictated by economic pressure domestically and also the extent to which [Vice President Nicolas] Maduro, if he wins election, needs to shore up his base.”

Velasco said that the most likely initial step the government would take to repair its balance sheet would be to reduce the volume of subsidized petroleum products it sells to regional allies. These include members of Petrocaribe SA, which includes many Caribbean Sea nations, and members of the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas or ALBA, which includes Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua and Cuba.

However, Cuba may continue to receive subsidized petroleum from Venezuela, because it provides both a cadre of medical personnel to the country and state security agents assigned to chavismo leaders like Maduro.

If those steps do not increase cash, the government will have to consider turning to foreign energy companies.

“On one hand, [Maduro] will need to continue the anti-imperialist rhetoric of Chavez,” if only to allay fears of some that Chavez’s policies may not survive him, Velasco said. “On the other hand, if they are strapped for cash, they might have to make some deals with foreign companies.”

These would be deals for access to onshore shale oil properties and Orinoco Belt, the world’s single-largest crude oil reserve.

"Foreign oil companies desperately want to get in on Venezuelan oil, and, because of that, they’re very likely to accept deals that are not favorable on the assumption that this is a long-term gamble and over time terms may improve,” Velasco said. “Right now, they just want to get in on the game. So in short term, they are willing to accept unfavorable deals.”

He said the first type of foreign oil company Caracas might turn to with sweetened contract terms will be state-owned companies like Brazil’s Petroleo Brasileiro SA or Petrobras and Russia’s Gazprom OAO.

After that would be private oil companies like Exxon Mobil Corporation (NYSE:XOM) and BP PLC (LON:BP).

“What the government may do is ease the conditions of production-sharing agreements to give companies a slightly bigger share, Velasco said. “You might have a deal that calls for a 50-50 split changed to 70-30 but only for the short term. It would be renegotiated after a brief period. It all depends on how cash-strapped the government feels.”

One of the complicating factors is pending arbitration between Venezuela and energy companies whose assets Chavez seized. One of those litigants is ConocoPhillips (NYSE:COP), once the biggest non-Venezuelan energy companies in the nation.

ConocoPhillips could benefit greatly from regaining its former assets, Fadel Gheit, senior oil analyst at Oppenheimer & Co., told the Christian Science Monitor. "The book value of assets that were confiscated was $4.5 billion [at the time]. The market value is now $20 billion to $30 billion. ... ConocoPhillips could eventually see a net gain of $10 billion."

ConocoPhillips isn’t holding its breath for a post-Chavez breakthrough.

“We don’t expect [his death] to have any influence on our arbitration hearing currently under consideration by the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID),” said ConocoPhillips spokesman Daren Beaudo, who also declined to “speculate regarding future opportunities in Venezuela.”

ExxonMobil also has a pending arbitration case against Venezuela, said company spokesman David Eglinton.

"The dispute is not over Venezuela's power to expropriate; the dispute is over Venezuela's failure to meet its obligation under applicable international law to pay compensation based on fair market value of the expropriated investment," Eglinton said. "We have no indication of when the ICSID decision will be given."

Once Caracas has trimmed its overseas oil subsidies, invited in state-owned oil companies and resolved disputes with private companies, it could turn to private drilling companies like Parker Drilling Company (NYSE:PDK), NYU's Velasco said.

Even if Venezuela's government opens its economy to the free market, there are two variables over which it has no control and which could bring the nation's whole economy to its knees.

One is China's willingness to keep lending to the chavismo regime, said Capital Economic's Rees.

“The Chinese government has lent nearly $50 billion to its Venezuelan counterpart in recent years, with the loans repaid with shipments of crude oil,” said Rees. “Those loans have been a key factor in the government’s ability to maintain an increasingly unsustainable balance of payments position.”

The other unknown over which the government has zero control is the market price of crude oil.

“Even if Mr. Maduro can secure continued funding from China, we suspect that it is only a matter of time before the flaws in Venezuela’s economic model come to the fore. A hollowing out of local industry through a program of nationalizations has left the economy increasingly reliant upon imports of many goods. But a lack of savings means that the authorities have only been able to sustain the current level of consumption via FX debt and high oil revenues. As a result, the economy is extremely vulnerable to lower oil prices. We have already penciled in a recession for this year. But if global oil prices fall below $100 per barrel for a sustained period over the coming years, as we think likely, then there is a risk that Mr. Maduro’s presidency will culminate in a balance of payments crisis and even a possible debt default.”

Taken together -- the factors that Caracas can control and those it can't -- authentic reform appears distant, if not chimerical.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.