Ancient Fish Fossil Could Explain Evolution Of Vertebrates, Including Humans

Researchers have examined a long-preserved fossil of a tiny fish, which existed on Earth more than 500 million years ago, and suggested that its remains could solve mysteries about ancient vertebrates’ lives and the story of their evolution.

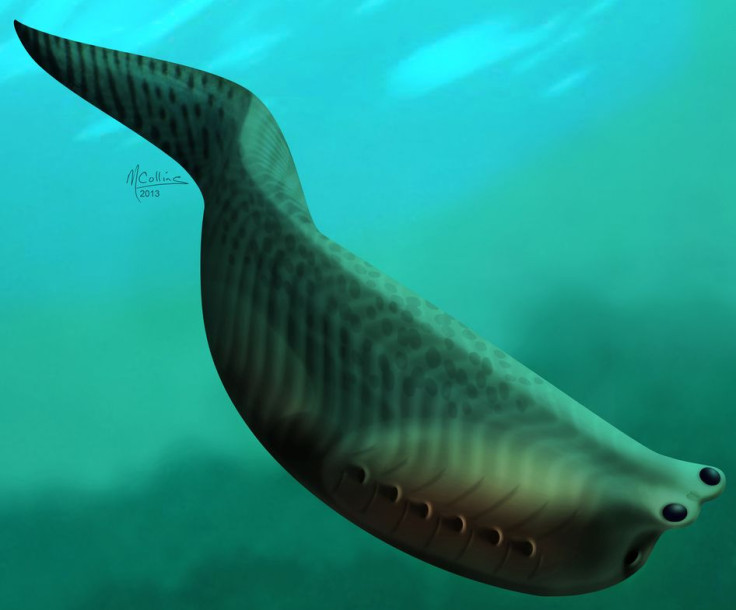

The fossilized fish, called Metaspriggina walcotti, was first discovered at the Burgess Shale site in Yoho National Park in Canada's British Columbia province in 1909, and is considered to be one of the rarest fish fossils in the world. The ancient jawless fish, which was no bigger than a human thumb, had gill structures that eventually developed into jawbones in jawed vertebrates, according to the researchers.

“For the first time, we are able to say this is really close to this hypothetical ancestor that was drawn based on a study of modern organisms in the 19th century,” Jean-Bernard Caron, a paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, and the study’s co-author, told the Christian Science Monitor.

According to the scientists, they studied nearly 100 specimens of vertebrates from several deposits similar to that found in the Burgess Shale dating from the Cambrian Period, which began about 542 million years ago. However, the most significant specimens for the study came from a new area of the Burgess Shale and were discovered by an expedition led by the Royal Ontario Museum in 2012 near Marble Canyon in Kootenay National Park in the Canadian Rockies.

“The exquisite preservation of seven almost identical paired (left and right) branchial bars composed of two elements each (ventral and dorsal) in one of the earliest known vertebrates in the fossil record called Metaspriggina,” Caron wrote in a report about the study, published in the journal Nature on Wednesday. “The first pair of gill arches is more robust than the others and presages the first step in the evolution of the jaws.”

The researchers said in the study that the first pair of branchial bars -- arches that support gills in fish -- in Metaspriggina would have evolved into jaws in vertebrates while the second pair would have gone on to support the jaw while the remaining five pairs may have been lost during the evolution process over millennia. In addition, the researchers also believe that part of the jaw bones would have evolved into small middle ear bones in mammals.

The study also revealed information about Metaspriggina’s physical characteristics. According to researchers, the fish had a small head, a wide front area behind the mouth and a flattened posterior area. Although the creature did not have bones, it possessed a skull made of tissues.

“A new Royal Ontario Museum-led expedition will return to Kootenay National Park this summer with the hope of uncovering new Burgess Shale-type Cambrian fossil sites and specimens, including new specimens of Metaspriggina and possibly other fish species,” Caron said, adding that there are many questions about Metaspriggina that will be addressed in future studies.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.