Portrayals Of Wall Street As Greedy, Selfish And Rotten - 100 Years Ago (Photos)

To many people who follow daily activities on Wall Street -- indeed, to many people who have money invested in any global stock or bond instruments and pay them even the minimum of attention -- something seems terribly wrong.

Banks, investment houses and other financial services firms can't seem to keep their names out of the headlines -- and they don't get there for discovering a cure for cancer. Instead scandals involving money laundering, rogue investing, fleecing customer accounts and taking big risks with the little bit of money held by small investors are all too typical. No wonder that Wall Street and its ilk around the world have such a bad name. Indeed, the enduring perception of financial services firms today is that they are greedy and care little about their customers; bank has truly become a four-letter word.

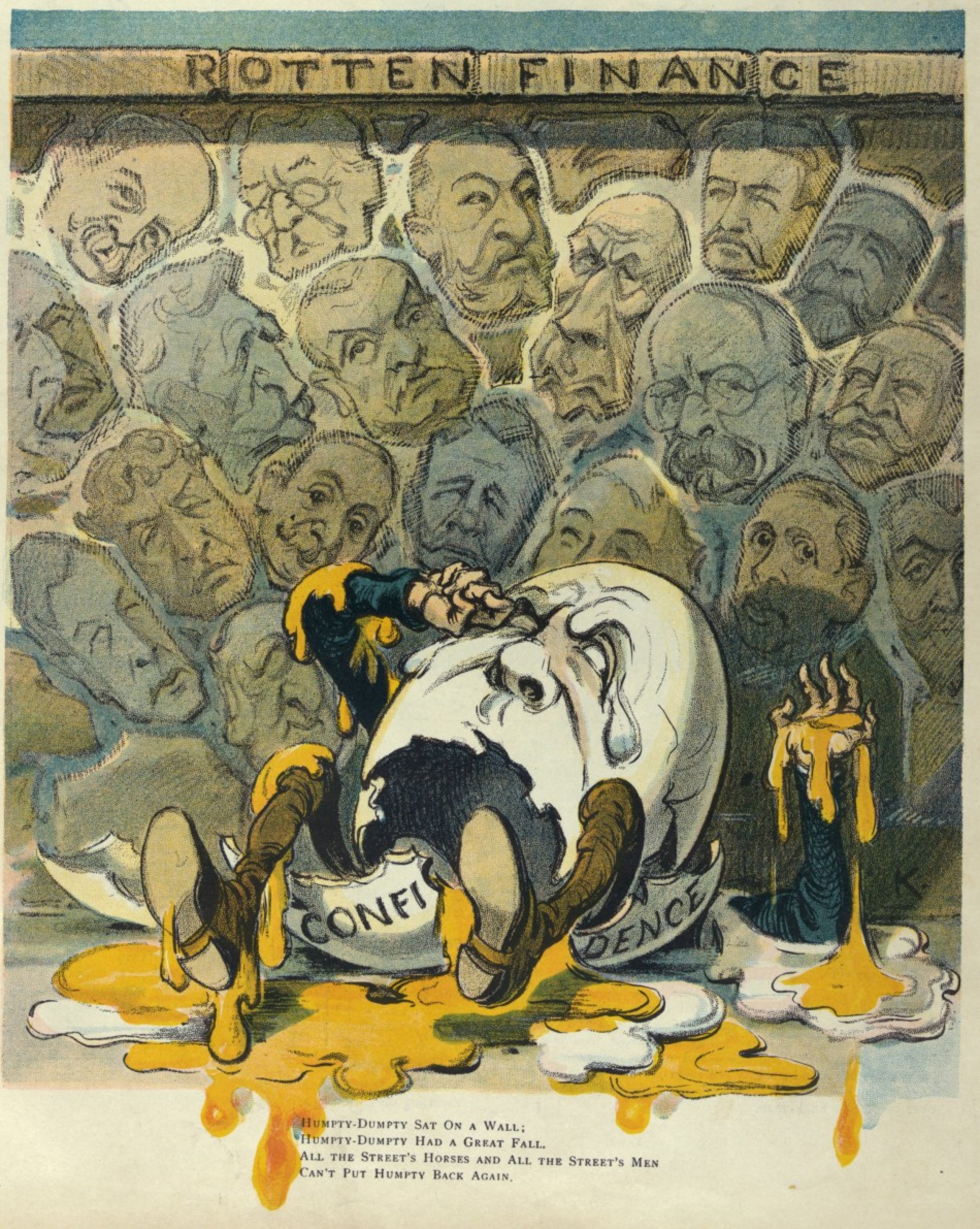

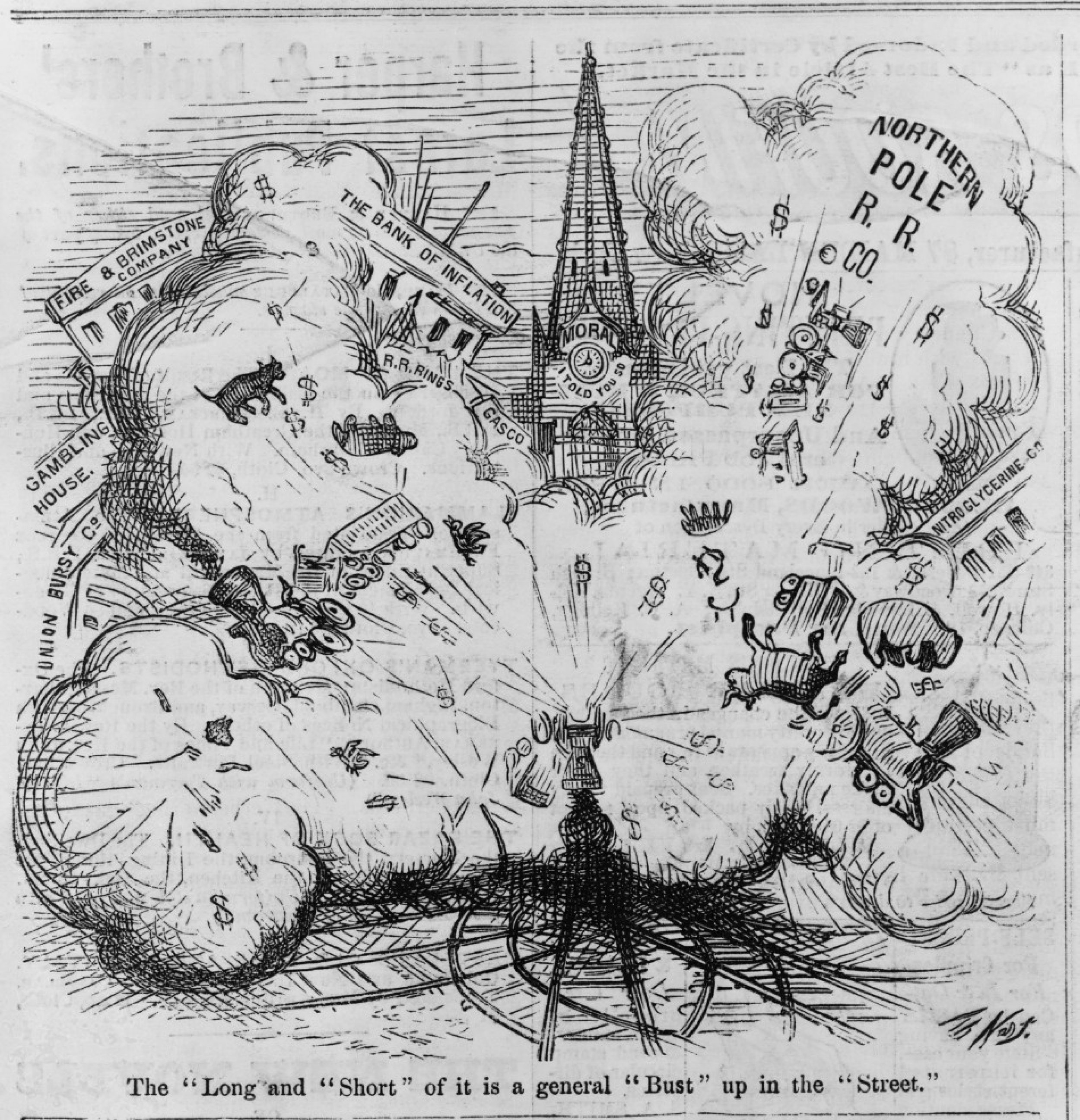

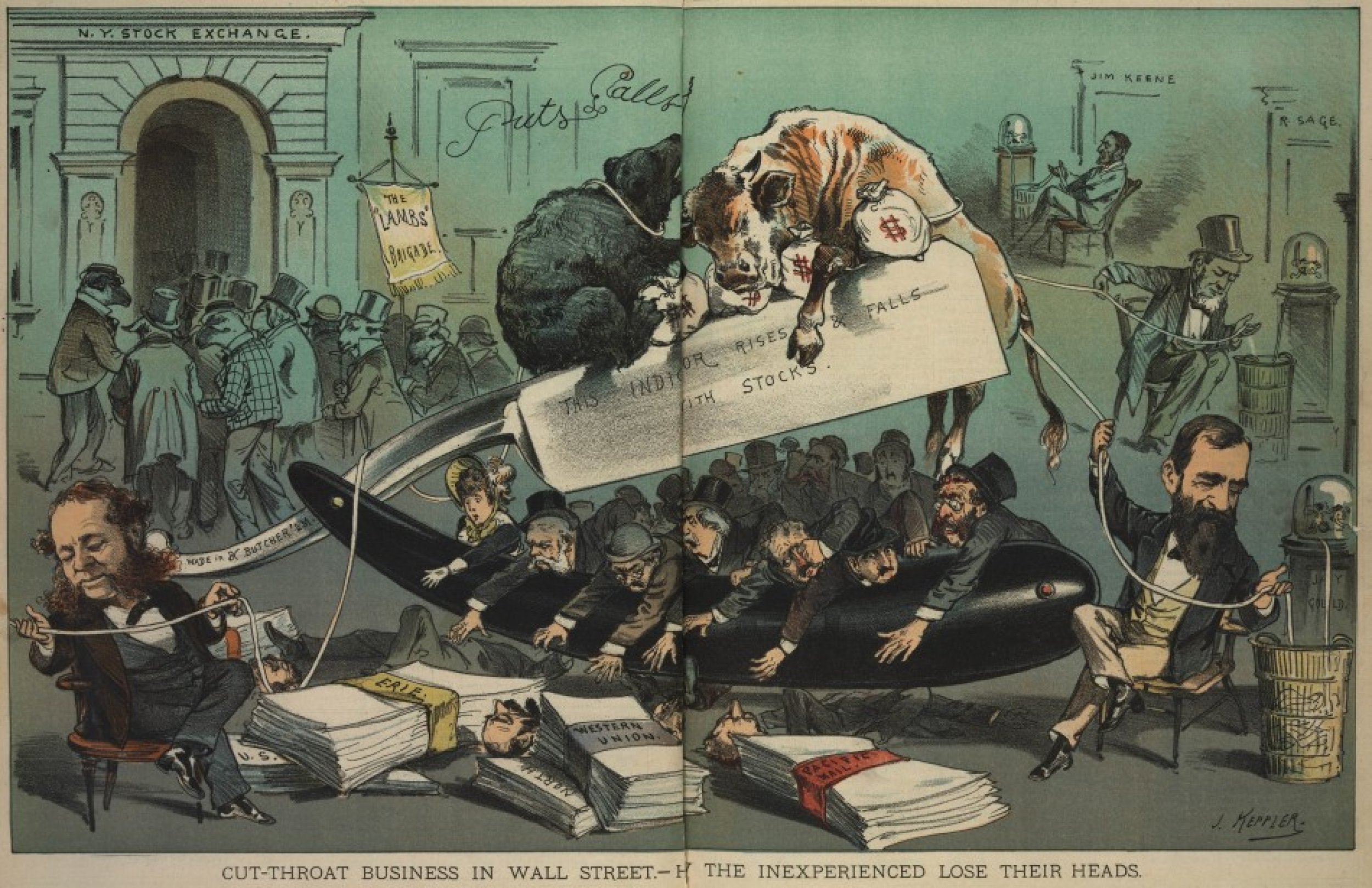

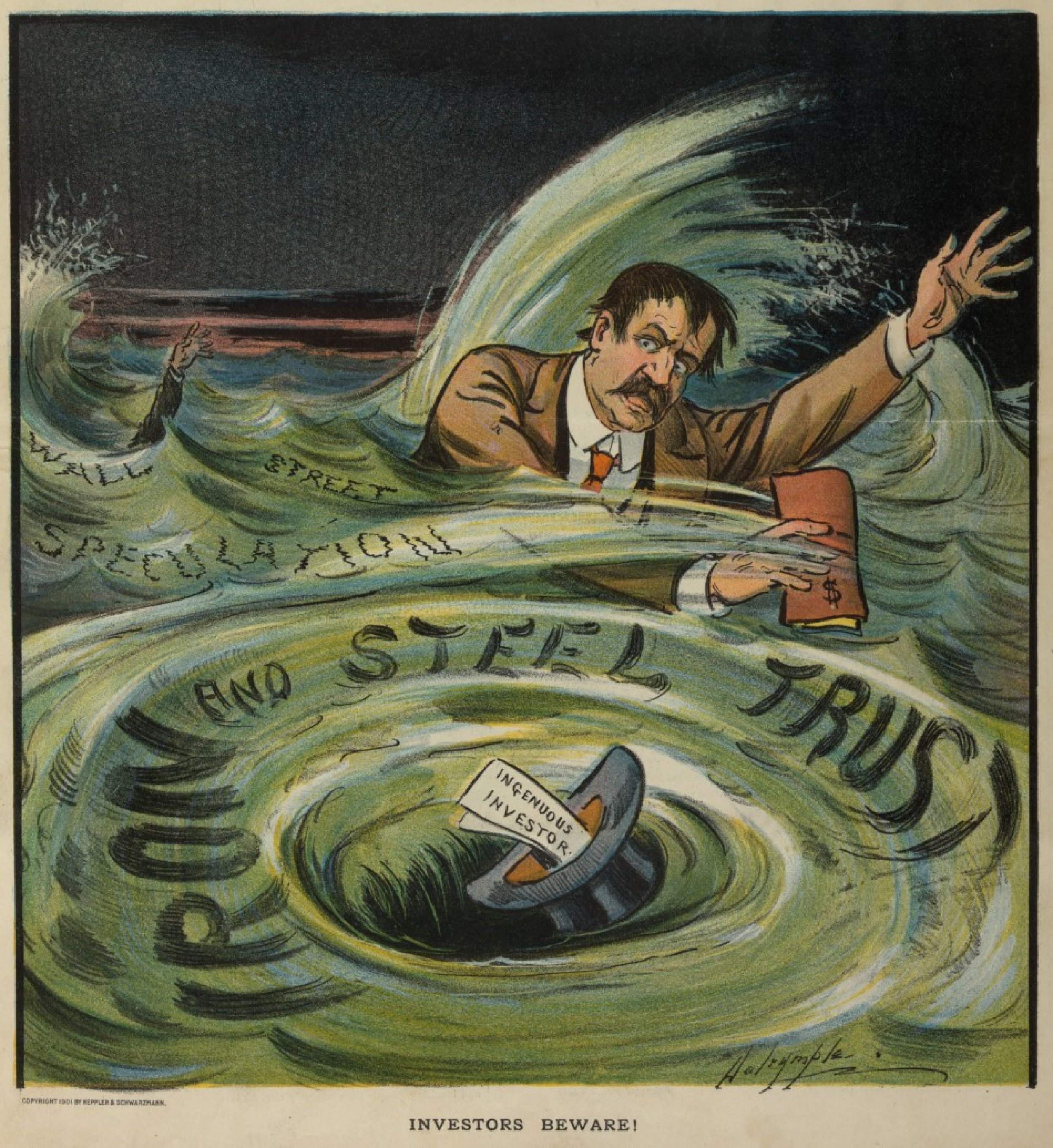

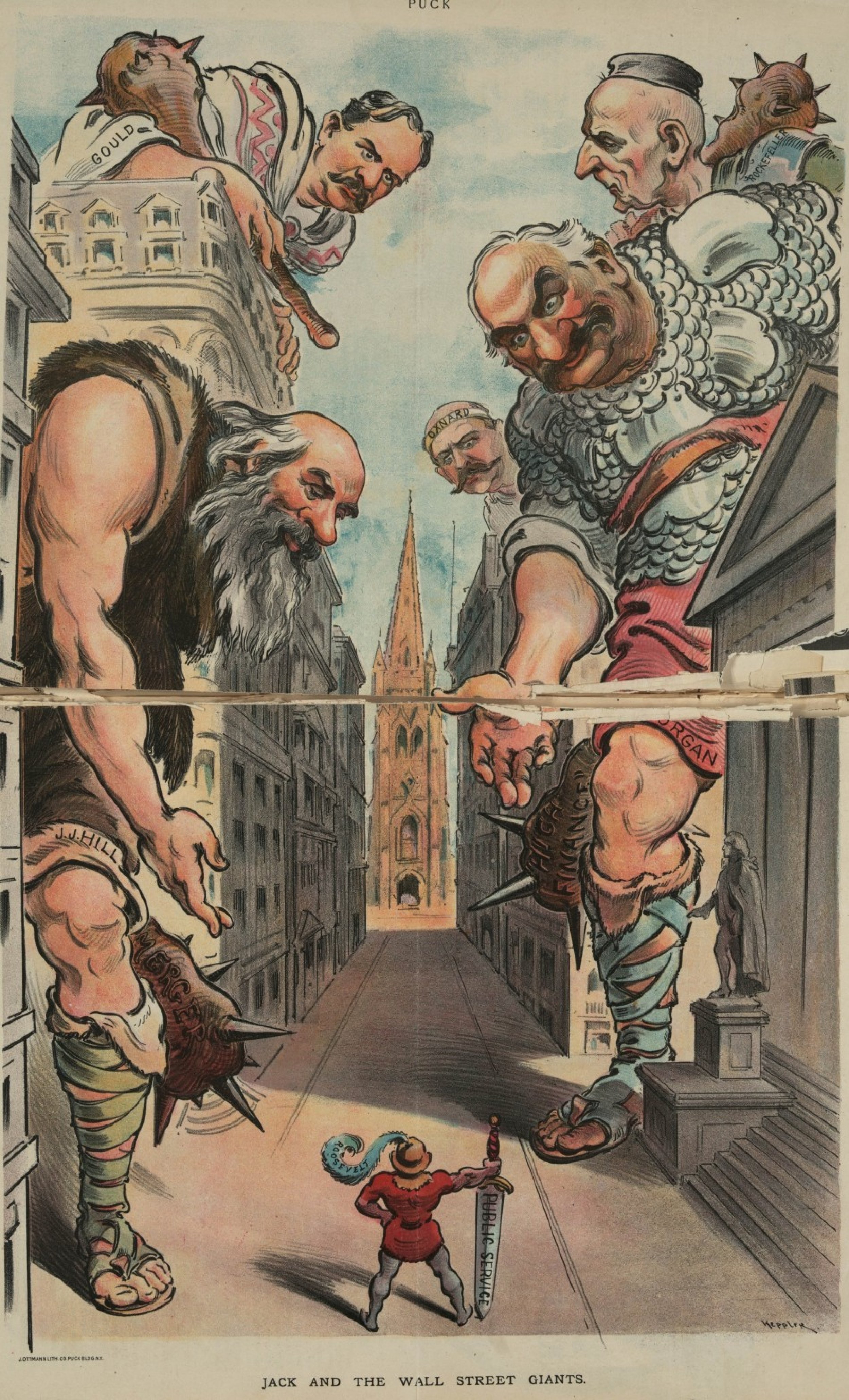

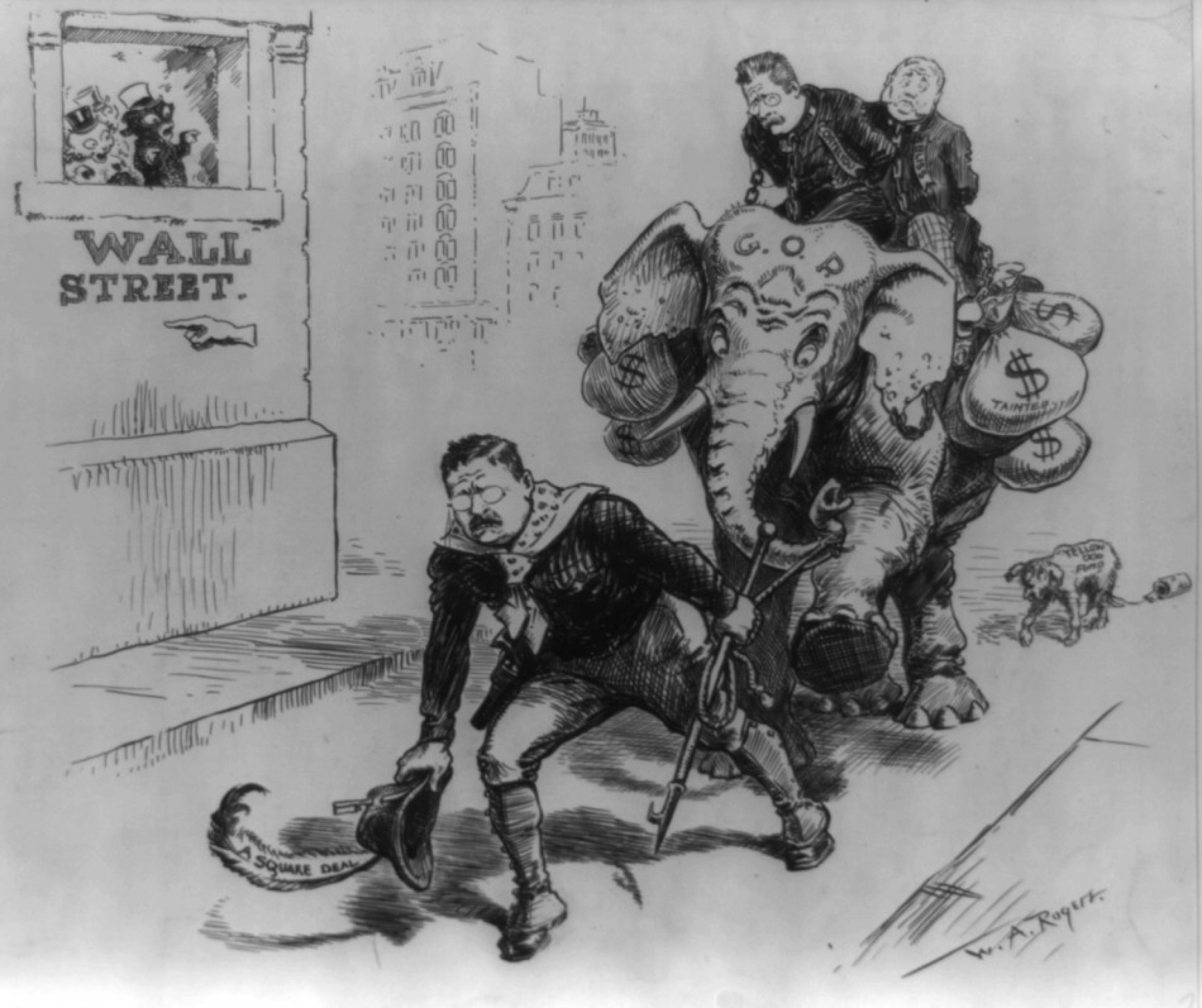

Recently, IB Times came upon a treasure trove of remarkable, hard-hitting editorial cartoons from the early 1900s that reveal again that the more things change, the more they stay the same. These wonderful illustrations show that a century ago, when most people did not have equity investments but rather kept their money in plain vanilla savings accounts, the public's view of Wall Street was similarly jaundiced.

“In some degrees the cartoonists were kind of spot on,” says Charles Calhoun, a Professor in the Department of History at East Carolina University who specializes in the U.S. ‘Gilded Age’ around the turn of the last century. “In the early 20th century, you were really coming into the era of big business.”

That is, big business as a malevolent force, populated by monopolists, crony capitalists and, worse yet, thieves.

It wasn't always that way. Around the time of the Panic of 1873, a financial crisis that triggered a half-decade global depression, Wall Street was well represented in newspaper cartoons but financiers at that time were seen as victims or, at worst, hapless bystanders in the calamities brought on laissez faire industrial capitalism.

In "Beyond the Lines", a book on pictorial reporting during the 19th century, City University of New York Professor Joshua Brown writes that illustrations “of Wall Street investors, stockbrokers, and clerks shown clamoring at the doors of the sealed Stock Exchange, or struggling in front of failed banking houses in 1873” were intended to elicit empathy among readers for mistreated people with legitimate grievances, like those participating in an urban riot.

“To readers glimpsing such scenes, “panic” indicated a specific type of rioting,” Brown writes of what he terms “engravings showing streets littered with wrecked fortunes.”

Indeed, in the late 19th-century, when the industrialist robber barons, who owned railroads, steel mills, coal mines, real estate and water works were common topics of devastating editorial cartoons, Wall Street was seen as merely another institution that these capitalists were abusing.

But by the early 20th-century, financiers had become interwoven with the robber barons in the minds of most Americans.

“You had people like Carnegie and Rockefeller that ran big companies, trusts, if you will. But it was the bankers that were then seen as the wizards putting together these gigantic corporations,” says Calhoun.

That increasingly dim view of money-brokering reached a boiling point in 1907, the year of another Great Panic, as it was widely perceived that powerful banker J. Pierpont Morgan used the crisis to solidify his stature and flex his political muscle -- lending money to failing companies and governments in exchange for a great deal of control over their future activities, in essence creating a “money trust.” The all-night meetings in Morgan's personal library in New York attended by the nation's top bankers to discuss solutions to the 1907 crisis only cemented the perception that Morgan and his compatriots had taken control of the country. As did the fact that both Treasury Secretary George Cortelyou and President Theodore Roosevelt bent over backwards to accommodate Morgan’s plans to handle the financial debacle, even when some of his ideas ran afoul of the law.

This new and expanded role for Wall Street -- the danger that many believed it held for the future of the country and individual economic mobility -- immediately became a prime topic for illustrations in the satirical magazine Puck, a liberal-leaning New York periodical. William Allen Rogers, the legendary political cartoonist who succeeded the famous caricaturist Thomas Nast at Harper’s Weekly, also poured a lot of ink on the topic, this time for the New York Herald.

Puck’s illustrations in particular are notable for their beauty, complexity and refusal to dumb down the somewhat complicated topic for the publication's audience. Some illustrations include references to works of classic literature and Greek history, for example.

The criticism in these cartoons include themes that would be very familiar today: Wall Street as a casino, the subservience of Congress to moneyed interests and the question of why financiers who break the law don't end up behind bars.

This first round of anger at Wall Street lasted well into the mid-1910’s and in some quarters beyond that. However, from 1913 on, a bear market and increased regulatory scrutiny was reflected in some cartoons with a dose of schadenfreude, manifested by editorial illustrators making fun of the “newly-poor” banking cohort.

Puck's founding family sold the magazine to newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst in 1917. The publication folded a year later.

What follows is some of the most intriguing and compelling Wall Street inspired political cartoons from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.