Behind The S&P 500 Index: How Stock Buybacks Fuel The Bull Market

The steady rise in U.S. stocks over the last six years, the third-longest bull market in history, rests largely on stock buybacks. That’s one of the conclusions Deutsche Bank global equity strategist Binky Chadha makes in his latest research note, which puzzles out the factors behind two decades of market vacillations.

“Market returns have been driven primarily by buybacks in the U.S.,” he writes. While this is likely no great revelation to many professional investors, who pay close attention to stock buybacks, it may surprise ordinary savers that stock-market gains stem more from companies gobbling up their own shares than from fundamental economic activity.

To reach this conclusion, Chadha uses a tool from elementary economics: supply and demand.

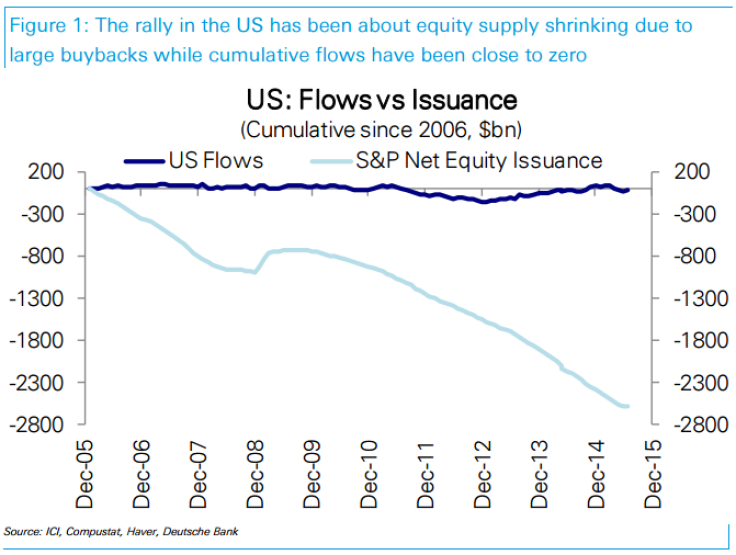

Like any other product, when the demand for equities rises faster than the supply does, prices should increase. Chadha measures supply as overall stock issuance minus buybacks. Demand is total inflows into mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), the two most attractive products for retail investors and retirement savers.

The gap between supply and demand is highly correlated with stock-market returns since 1995. Chadha finds that 74 percent of returns in the S&P 500 can be explained by the demand-supply gap.

It isn’t demand that has changed the past six years. Mutual fund and ETF inflows have held steady. The trend, Chadha writes, owes more to changing supply. “The framework attributes the current bull market to the steady shrinking of equity supply from buybacks,” Chadha writes.

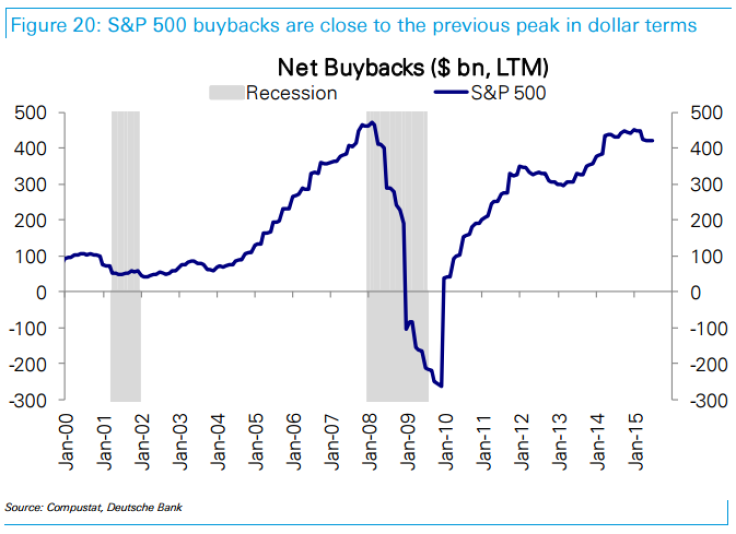

Since 2009, companies have bought up an average 2.5 percent of their market capitalization -- that is, the total value of their outstanding stock. In that time, corporations have spent at least $2.4 trillion repurchasing shares, the largest buyback binge since the market last peaked in 2007.

Recently, politicians have taken a closer look at the wider impacts of surging stock buybacks. In April, Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wis., asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to revisit its policies around stock buybacks, citing "mounting evidence to suggest that buybacks have a negative effect on jobs, wages and investment."

In Hillary Clinton's big policy speech last week, the 2016 presidential contender added buybacks to her list of economic concerns.

Corporations often justify buybacks by claiming company stock is undervalued. Buybacks, they say, express confidence in future gains. And with fewer shares outstanding, existing stockholders capture a greater portion of future profits.

General Electric and Apple have topped the buyback charts this year with plans to spend a combined $100 billion repurchasing their own stock.

But buybacks also goose a key Wall Street metric, one used both to evaluate company performance and to reward executives: earnings per share. By vacuuming up existing shares, firms can increase their EPS without making any fundamental business improvements. Research has shown that companies just about to miss EPS estimates perform larger buybacks.

A “safe harbor” rule passed in 1982 allows companies to carry out share repurchases without risking charges of stock-price manipulation.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.