Black Lives Matter 2016: Why Do Police Shoot To Kill? How Officers Are Trained In The Use Of Force

Police officers in the United States have killed black men for selling cigarettes, running away during a traffic stop, "behaving erratically" and hundreds of other seemingly mundane reasons that have sparked protests over police brutalty and fueled the Black Lives Matter social justice movement's call for police reform.

Law enforcement officials claim they must shoot to kill instead of say, trying to take a suspect down with a bullet wound in the foot, because they face intense pressure to make quick public safety decisions when confronting what could be a dangerous suspect. That means officers are trained to shoot at "center mass," or the area making up a human's chest region, to ensure the target is hit and any imminent threats are stopped.

"Killing isn't the objective," Geoffrey Alpert, a professor at University of South Carolina who researches high-risk police activity, told Cleveland.com after local police killed Tamir Rice, 12, for playing with a toy gun that looked real in a public park in 2015. "The objective is to remove the threat."

Civil rights activists, however, argue that regardless of whether law enforcement's shoot to kill policy is a best practice, recent cases of police shootings involving black men and women suggest police officers are more likely to find black suspects a threat and shoot them compared with non-black suspects. Many point to the recent arrests of Dylann Roof, a white man charged with killing nine African-Americans in a church in South Carolina in 2015 who was taken by police officers to Burger King during his arrest, and Ahmad Khan Rahami, who was arrested earlier this month without incident after a shootout with police following a series of bombing attacks Rahami is suspected of carrying out in New Jersey and New York.

More recently, protests calling for law enforcement reform have unfolded across the nation after the police shooting deaths this month of Terence Crutcher in Tusla, Oklaholma, and Keith Lamon Scott in Charlotte, North Carolina.

"I see incidents with a white person with a gun on their hip and ... they don't pull their gun. They pull their Taser to calm them down," Travis Haynes, 35, of Orlando, who is black, told the Associated Press. "But when it comes to a black man, the first thing they do is draw their gun."

The International Association of Chiefs of Police describes use of force as the "amount of effort required by police to compel compliance by an unwilling subject." A national database on officer-involved shootings involving excessive force does not exist, so it's not exactly clear how often police shoot to kill versus using other methods of force, such as defusing a situation by talking down a suspect.

In moments of uncertainity, law enforcement officials say their personal safety is a concern.

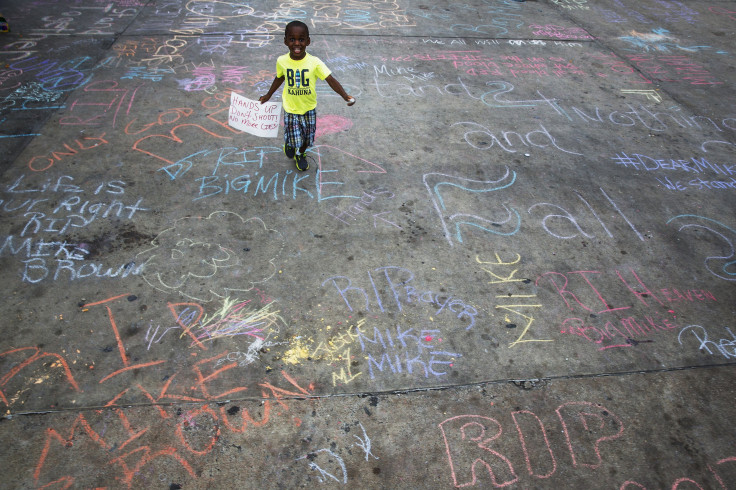

"Officers aren’t required to risk their lives unnecessarily," David Klinger, an associate criminal justice professor at the University of Missouri–St Louis and a former officer with the Los Angeles police department,explained to the Guardian after the fatal 2014 police shooting in the St Louis area of Michael Brown, an 18-year-old black teenager who was stopped by police because he was suspected of stealing cigars from a conveinance store.

Hubert Williams, a 30-year veteran officer, said police must shoot to kill or not at all.

"[An officer] wouldn't be justified in shooting unless there is a threat to his life," Williams said. "If there's a threat to his life, he has to take counter measures against that threat. So he's going to shoot not to stop him – he's going to shoot for the kill zone."

Police officers are trained to use force when their lives or the lives of someone else is in danger, according to the Department of Justice's National Institute of Justice. "There is no single, universally agreed-upon definition of use of force," the institute's webpage explains. "Officers receive guidance from their individual agencies, but no universal set of rules governs when officers should use force and how much... "Situational awareness is essential, and officers are trained to judge when a crisis requires the use of force to regain control of a situation. In most cases, time becomes the key variable in determining when an officer chooses to use force."

Public safety advocates have sought to limit shoot to kill policies in the past to limited success. A 1985 Supreme Court ruling found officers couldn't shoot a suspect just because they were fleeing. In New York, lawmakers tried in 2010 to push a "minimum force" bill that would require officers to shoot at suspects only to wound them, but failed to get it through the state Assembly.

Police should practice using basic verbal and physical restraint instead of lethal force when possible, the National Institute of Justice states. "Use of force is an officer’s last option — a necessary course of action to restore safety in a community when other practices are ineffective," it states.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.