On The Borderline: Sudan, South Sudan Negotiate As Time Runs Out

The situation is desperate for Sudan and South Sudan this week, as leaders from both countries meet in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, to work out a deal on border disagreements and the resumption of oil production.

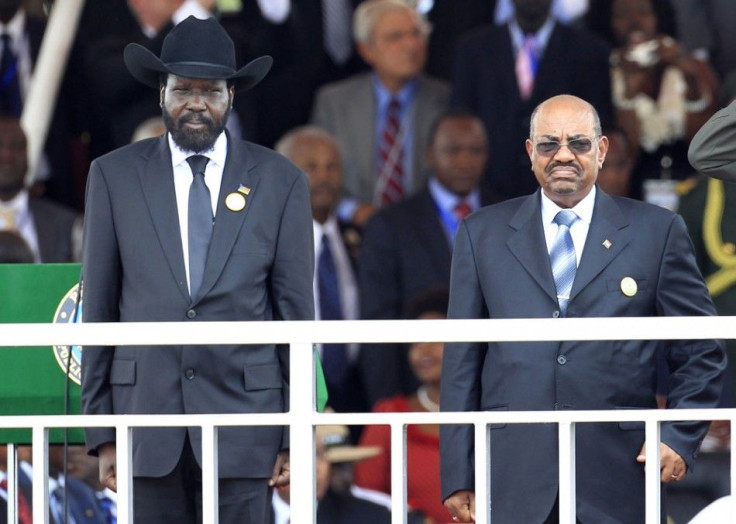

Sunday was the first time in more than a year that South Sudan President Salva Kiir met with Sudan President Omar al-Bashir in an official capacity, according to Reuters. The leaders are working with moderators from the African Union; if they cannot settle their differences, they may face sanctions from the United Nations.

At stake are the livelihoods of the long-suffering residents of both countries. The continued standoff between Sudan and South Sudan has devastated standards of living across the board, and at the heart of it all is a violent border zone that still defies clear-cut delineation.

The two countries were united until only recently; South Sudan officially split from its northern neighbor on July 9, 2011. The South had long suffered under Bashir’s dictatorial regime, which still reigns in Sudan’s capital city of Khartoum. Kiir now leads South Sudan from its new capital, Juba.

The split was meant to achieve peace after decades of conflict, but clashes continued. Part of the disconnect has to do with religion; the Sudanese are mostly Muslim, while South Sudan is dominated by animists and Christians.

But as the country works to forge lasting peace, oil and land are the real sticking points.

Oil was the main source of revenue for pre-division Sudan. But when South Sudan broke away last year, it took 75 percent of the country’s oil fields with it. Sudan retained the pipelines to transport the fuel and turn landlocked South Sudan’s crude into a marketable commodity for both countries.

In order to keep the oil industry sustainable, both countries would have had to work together. But continuing conflicts have made this impossible.

Amid violence in border areas, disagreements over crude transport fees and allegations of overdue payments, South Sudan shut down its oil production in January. Quite suddenly, both countries lost their major source of revenue, and today, the citizens of both countries are still paying a heavy price.

In Sudan, monthly inflation has exceeded 40 percent, raising the cost of living exponentially. In an attempt to save revenue -- and despite recurring protests in Khartoum -- the Bashir regime has implemented harsh austerity measures: lifting fuel subsidies, cutting public spending and increasing taxes.

Meanwhile, South Sudan continues to suffer from a dismal lack of development. Most South Sudanese are subsistence farmers, but better infrastructure could modernize agricultural practices to increase profits. The country is in desperate need of paved roads, a stable electrical grid and facilities for education and health care. But as long as internal and external conflicts force Juba to spend more on defense than development, the country’s 10 million people are in dire straits.

If Kiir and Bashir can reach a comprehensive agreement in Addis Ababa, these serious problems can begin to be addressed.

Luckily, they aren’t starting from scratch. Juba and Khartoum have already decided on mutually acceptable transport fees: the amount per barrel that South Sudan will have to pay Sudan in order to use its pipelines. The United States will also help to cover some lost revenues for Khartoum, working through China and several Arab Gulf states since direct payments are prohibited by sanctions against the Bashir regime.

Oil isn’t crossing the border yet -- partly because no one can be sure where the border is. The lines are hazy for a number of reasons: displaced persons on both sides, allegations of government-condoned violence, contested territorial claims, and seasonally migrating tribes that habitually cross the new borderline.

As talks progress in Addis Ababa, it seems likely that Kiir and Bashir will establish demilitarized buffer zones along the border’s most volatile areas. They are also expected to grant citizens of each country residency rights in the other.

A concrete delineation of territories is the ultimate goal, but that could take months or even years.

For now, any solution -- no matter how short-term -- could motivate South Sudan to start pumping the crude that both economies so desperately need.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.