Brexit: UK’s Cameron Faces Crunch Time In Negotiating Deal With EU That Must Pass Inspection At Home

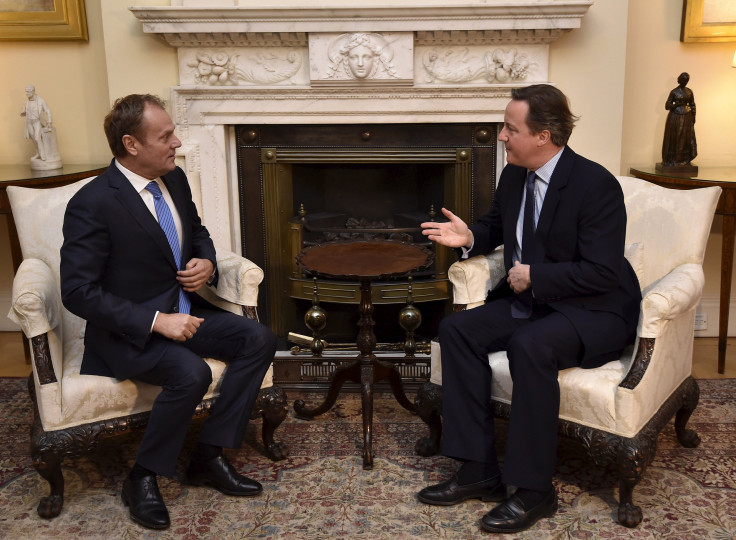

It’s crunch time for David Cameron. The British prime minister, trying to create a long-term consensus for Britain to stay in the European Union, now has perhaps six months to nail down, and sell, his new version of membership in the 28-nation bloc to fellow European leaders and fellow Britons.

EU leaders will meet in Brussels Thursday — and on Friday over an “English breakfast” — to discuss Cameron’s proposals to modify the country’s membership in the EU in a way that would then win majority support in a referendum in Britain later this year. Firming up a deal in Brussels won’t win the referendum for Cameron, but a diplomatic failure this week would put wind in the sails of EU critics in Britain.

“A disastrous European Council would risk delivering momentum to the ‘out’ campaign at a time when overall public sentiment towards the EU and the European project remains very negative — on migration, borders, economy and security,” said Mujtaba Rahman, the practice head for Europe at the Eurasia Group.

Indeed, polling shows Britons roughly evenly divided on the question. But there are enough unsure voters that missteps on either side will matter as much as their proponents’ overall ability to make their case in the upcoming referendum fight.

A YouGov survey for the Times of London early this month found that 56 percent of those who had decided wanted to leave the EU. But about 19 percent of those questioned hadn’t made up their mind, suggesting that Cameron has swing voters he can convince.

If Cameron reaches an agreement in Brussels, he could announce a date for a referendum this summer, effectively throwing down the gauntlet to members of his own party, and to a national media for whom anti-EU sentiment is bread and butter.

In the view of most analysts, a “Brexit” — as the possible departure from the EU has become known — is still less likely than approval of whatever agreement Cameron’s government does reach with other EU countries.

Leading lights of Cameron’s Conservative Party, which is divided on the matter, back EU membership, and luminaries such as former Prime Minister John Major will campaign in favor of the EU. With the opposition Labour Party supporting Britain in the EU, Cameron stands a good chance of winning a clear majority, and answering the European question for a generation.

“The debate will be interesting, and helpful for the greater public as well, because, to the extent it has not already done so, it will force every leading Brit — most of whom [are] ever so critical of everything European — off the fence to declare whether they, when all is said and done, think the EU is a good or a bad thing for the U.K.,” said Erik Nielsen, chief economist for UniCredit in London.

But formidable obstacles stand between now and a majority.

The negotiation between Cameron and other EU leaders turns, politically speaking, on how much they are willing to give a country from which much anti-EU vitriol has flowed. The answer to that question will turn on how convinced they are that Cameron can deliver a strong consensus for EU membership in Britain. And that will turn on how well Cameron can sell his package through the filter of a skeptical British press.

The core substantive question, from a political standpoint, involves the ferociously populist debate of whether migrants from the rest of the European Union cost or contribute to the country’s welfare.

The evidence suggests that nearly 100 percent of EU migrants to Britain come there to work, and since unemployment benefits only reach about 20 percent of wages, they have little incentive to loaf, according to a study by Peter Dixon, an economist with Commerzbank in London. But myths abound, so Cameron has been drawn into an intricate negotiation over welfare benefits that has inevitably rankled newer EU countries, such as Poland.

Britain is seeking an “emergency brake” that would let authorities curb benefits for some EU migrants who are working, while other countries have countered with the idea of a “tapering mechanism” that would allow a measure of benefits, provided the workers are contributing to the British social system.

Polling suggests the swing voters — those undecided on Britain’s EU membership — care about the migration question. According to Daniel Vernazza, a UniCredit economist focused on Britain, Cameron’s challenge will be to steer through the static of a press that’s always skeptical of Brussels and take his case directly to the voters in a referendum, likely this June.

“The actual deal and how it’s portrayed will really matter for the referendum in the U.K.,” Vernazza said. “Whether Cameron is perceived as ‘winning’ will be key.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.