California Death Penalty: Golden State Latest To Weigh Benefits, Costs Of Capital Punishment

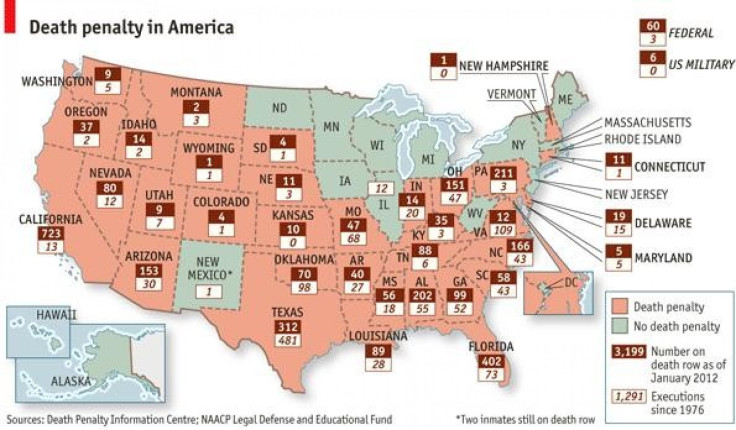

California could potentially become the 18th state in the nation to abolish the death penalty in November, when residents are set to vote on a ballot measure that would replace capital punishment with a sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole.

During the last five years, four states have replaced the death penalty with life imprisonment without parole, with advocates expressing frustration with both the rarity of executions and the hefty price tag attached. Connecticut will soon be the fifth state to follow suit after its Legislature narrowly repealed the state's capital punishment law in early April.

Whether or not the recent uptick in death penalty repeals is the start of a national trend is difficult to gauge. It is worth noting that although capital punishment is still legal in more than 30 states, actual executions are extremely rare in most regions of the country. In fact, most death row inmates are generally more likely to die of old age than by an executioners needle.

Thirty-two of 53 jurisdictions in the U.S. (including 50 states, the District of Columbia, the Federal government and the Military) have not executed a prisoner in the last five years, reports the Death Penalty Information Center, with more than half of the states conducting no executions since the U.S. Supreme Court rescinded a national ban on capital punishment in 1976.

U.S. Executions Overwhelmingly Centered in South

Capital punishment was suspended in the U.S. between 1972 and 1976 as a result of the high court's decision in Furman v. Georgia. The justices were unable to reach a consensus in their legal justification for ruling against the application of the death penalty, leading to a de facto moratorium on inmate executions throughout the U.S. until it was reaffirmed by Gregg v. Georgia in 1976.

Thirteen states executed a death row prisoner in 2011, with only eight of those executing more than one inmate that year. The numbers show that capital punishment has, in recent years, been primarily relegated to the southern region of the country. Texas performed 13 executions last year, more than double than its closest competitor Alabama, which executed six inmates. Mississippi (3), Oklahoma (2), Florida (2) and Arizona (2) also saw more than one execution occur that year.

Almost one-third of all executions that have taken place since 1976 have occurred in Texas, which performed 481 death row executions during that period. Of the remaining non-Texas executions, a majority have been clustered in a small group of southern and Midwestern states.

The sheer and obvious finality of sentencing a prisoner to death is one of the prime objections raised by opponents of capital punishment. There have been an average of five death row exonerations per year in the U.S. between 2000 and 2011, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Since 1973, more than 130 people have been released from the death row after evidence of their innocence came to light.

The Race Factor

The racial discrepancies between death penalty convictions and executions in the U.S. have also led some opponents to question the validity of the system. For instance, since 1976, 75 percent of murder victims in cases that ultimately resulted in execution were white, even though nationally only about half of murder victims are white. That isn't to say that white defendants have not been penalized by the justice system; more than half -- 726 -- of the 1292 prisoners who have been executed since 1976 were white, while 443 were black and 99 were Hispanic.

However, a racial imbalance is found when comparing the executions of defendants involved in interracial murders. The Death Penalty Information Center reports 18 white defendants have been executed for murdering a black victim over the past 36 years. In contrast, 253 black defendants convicted of murdering a white victim have been met with capital punishment.

The prevalence of perceived racial bias in death penalty convictions led to the passage of North Carolina's Racial Justice Act in 2009. The law allows capital defendants to use statistical evidence to show racial bias was a factor in decisions to seek or impose the death penalty at the time of his or her trial, a particularly important factor in North Carolina since more than half of the state's death row population is black. Those who successfully prove that racial bias tainted the decision can have their sentences commuted to life in prison without parole.

Last week a North Carolina judge issued a historical first ruling under the law, finding that black jurors had been systematically barred from capital cases at the time of defendant Marcus Reymond Robinson's trial.

Death Penalty Outeighs Cost of Life Imprisonment

Studies conducted in multiple states have concluded that carrying out inmate executions is ultimately more expensive than sentencing them to life without parole, further leading capital punishment opponents to question the logic of the system.

California taxpayers alone have spent more than $4 billion on the 13 inmate executions the state has performed since 1978, according to a three-year study published in the Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review last year. The study estimated the costs of capital trials, enhanced security on death row and legal representation for death penalty defendants adds $184 million to California's budget each year.

Similar studies have been conducted in at least 9 other states since 2000, all of which have concluded imposing the death penalty is exorbitantly more expensive than a life-without-parole sentence. A 2001 report from the National Bureau of Economic Research concluded that capital crime trials place huge and unexpected burdens on country budgets, often leading them to counter those high costs by defunding public projects and increasing taxes.

--

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.