California Drought 2014: State Officials Push For Water Conservation As Climate Change Threatens Future Drought

With California in the grip of a crippling drought, state officials and researchers are pushing for a culture of conservation -- not just for this summer but in anticipation of what, thanks to global warming, is likely to be a drier future.

“Droughts will happen again because of our changing climate,” Karen Ross, secretary of the California Department of Food and Agriculture, told reporters on Tuesday. “We’re really focused on looking at … how do we put resiliency into our systems at the local regional scale and the state scale to be able to survive droughts better.”

Her statement followed a separate announcement Tuesday morning that state water regulators are expected to pass the first-ever emergency water restrictions for the entire state. The rules, if passed, will levy fines of up to $500 a day on Californians who over-water their yards or hose down sidewalks and driveways.

Scientists aren’t certain whether the now three-year-long drought is a direct result of climate change. A recent study by Utah State University scientists found a possible link, but other researchers have been reluctant to pin the current drought on the rise in global greenhouse gas emissions.

Over the long term, however, scientists agree: As climate change messes with weather patterns, California will likely experience longer and more severe droughts in the coming decades, threatening the sustainability of the state’s main water supply system.

The sector likely to be hit the hardest is agriculture, which brings in nearly $45 billion each year for farmers and ranchers and accounts for about half of the fruits, nuts and vegetables grown in the United States. In 2014 alone, the current drought is expected to cost the agricultural sector about $1.5 billion in lost crop revenues and dairy and livestock value, according to a new economic impact study by researchers at the University of California at Davis. Secretary Ross, who commissioned the study, accompanied the report’s authors today at a press event in Washington, D.C.

Overall, the drought could cost California’s economy $2.2 billion this year, with more than 17,000 seasonal and part-time jobs lost due to declining agricultural productivity, the study said.

Farmers in California’s interior Central Valley could start seeing their groundwater wells run dry within a year if rain and snowmelt remain scarce in the region, said Richard Howitt, a professor of agriculture and resource economics at UC Davis. Cotton crops, small-scale vegetable and citrus farms, and almond orchards could feel the most pain, while coastal producers like Napa Valley wineries will feel the impact less. “In certain parts of the Central Valley, it’s extremely bad,” Howitt said at the report’s launch event.

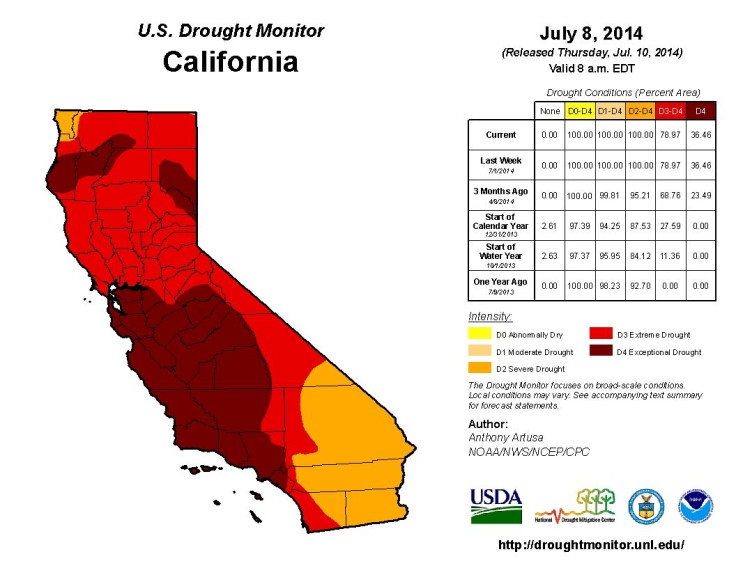

Nearly 80 percent of California is now under “extreme or exceptional” drought conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. The drought has a statistically strong chance of continuing into 2015, even if the El Niño weather event brings heavy rainfall later this year, researchers say.

In the long run, climate change-related drought could require the state to slash its net water usage by 15 to 20 percent, Howitt said. Measuring existing groundwater reserves will be critical to managing those scarce resources -- something that state regulators don’t currently do. California is the only state in the Western U.S. to not measure groundwater, in part because the state up until now had abundant reserves, he noted.

“We’re like somebody who is so rich they don’t have to balance their checkbooks, because we still think we’re in a groundwater-rich era,” Howitt said. “It made sense for California when we had lots of water. It doesn’t make sense any longer."

California’s $85 billion outdoor recreation industry is also suffering this year -- and it will likely continue to feel the effects down the road.

Already this summer, sport fishing tournaments, yachting races and white-water rafting trips have been scrapped because water levels at lagoons and rivers are too low, the Los Angeles Times reported in June, adding that the dry weather could financially hurt rural communities that depend on skiing, fishing and camping.

The low water levels follow the scant snowfall last winter that forced ski resorts across California to close early. Ski visits shrank to 4.9 million last season from the five-year average of 6.8 million visits, according to the California Ski Industry Association, the LA Times noted.

California officials have struggled to curb water use by residents. In January, Gov. Jerry Brown declared a state of emergency and asked residents and city officials to voluntarily cut their water use by 20 percent. So far, however, usage is down just 5 percent. Part of the reason is that in urban areas, where residents are prone to over-watering their yards or scrubbing their cars, the effects of the drought are far less profound than they are on ranches and farms, Ellen Hanak, an economic and senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, told International Business Times.

She said the proposed penalties that regulators are considering are mostly symbolic, and that the state won't likely bring in heaps of cash from the penalties. “The state would like to send a message that we should all take this [drought] seriously. There’s no reason anywhere in the state to waste water,” Hanak said. “Most urban areas are doing okay, but if it is dry next year, that might not be the case.”

Even as climate change threatens more droughts for California, the state’s economy could remain stable -- if state regulators, farmers and general consumers figure out how to make do with less water and manage systems more efficiently, said Jay Lund, who directs the Center for Watershed Sciences at UC Davis and co-authored the impact study announced Tuesday.

“We do see inconveniences and we do see costs … But it’s not catastrophic if we manage it well,” he said. “Water is a scarce commodity in California, and we have to act that way all the time.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.