Cassini Grand Finale: Father & Son Researchers Say Goodbye To Spacecraft Together

Early Friday morning, before the sun rises over Pasadena, Calif., hundreds of scientists and researchers will gather to say goodbye to Cassini. The unmanned spacecraft that launched nearly two decades ago has been sending groundbreaking data on Saturn and its moons since its arrival at the planet in 2004. The craft is running out of fuel so NASA is disposing of it by setting it on a path to burn up in Saturn's atmosphere. While there will be few dry eyes Friday, Cassini's grand finale will be especially emotional for Larry and Jason Soderblom.

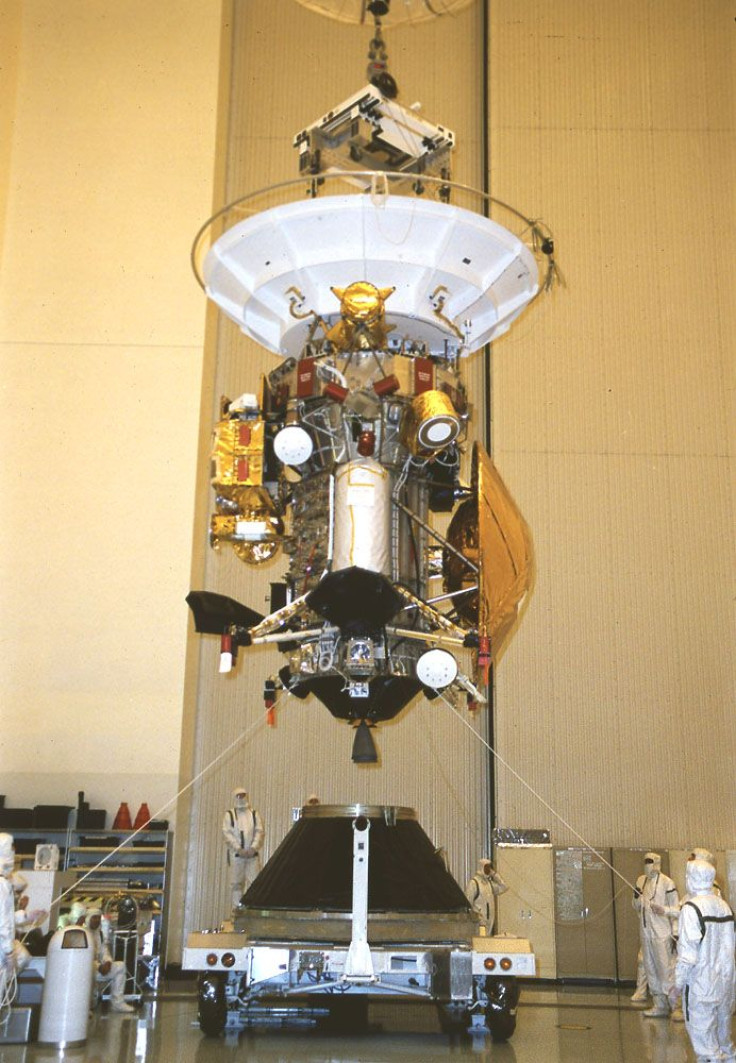

When Larry, a geophysicist with the United States Geological Survey, started working on the plans for the Cassini craft in the 80s, his son Jason was about 10. Back then, neither of them knew they’d eventually end up working together on the science made possible by the Cassini mission.

“He was so involved in so many different things that at that time the cool things were Galileo and some of the Mars missions,” Jason Soderblom, a research scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told International Business Times about his father’s involvement with Cassini. The Cassini mission could barely compete in dinner time conversation up against missions to mars, especially not when it was only in the planning stage. “The planning phase doesn’t make as much headline at home,” Jason said. The launch of the craft didn’t happen until years later, around the time that Jason was finishing high school.

Even when Cassini launched neither father nor son knew that project would cause their careers to cross paths. “I peripherally followed my father's career through high school and early college but it wasn’t actually really until the latter part of my undergraduate college career that I started really becoming more interested in the type of work he did,” Jason said.

The spark that ignited the initial interest was a trip to visit his father at work, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“He got involved with the engineers doing a bunch of programming with the Pathfinder mission and after his six-day stint he was ready to leave and the engineers said ‘Well Jason you can’t leave your software’s not done.’ So he stayed another week or so and he just got hooked,” Larry Soderblom told IBT.

That’s pretty much how Jason remembers it as well, he went to JPL got involved in a small project and “ended up out there for several weeks in the end if I recall correctly, which was great, a lot of fun, and that was kind of the beginning of my involvement in planetary science.”

After finishing his undergraduate career he went on to Cornell and eventually ended up at MIT. “I don’t know that I ever expected him to go directly into the same general field,” Larry said of his son.

Regardless of whether they expected it, the two have worked together, and published scientific research papers together. “When we started I was kind of the tutor and he the tutoree,” Larry said. But he noted that their working relationship didn’t stay that way for long.

“He became more and more mature and adept at what he was doing and we soon became equals...I have to argue now that when we work together he’s usually in the lead,” Larry said

Both of them have ended up studying Titan and the data Cassini has been able to collect on the moon. “Most of the papers that we’ve publish that either of us have published in the last decade at least or decade and a half we’ve both been on,” Jason said.

Come Friday, they’ll both be at Cal Tech. “We’re going to fly it into Saturn and it will be just quick and just like a meteor going into the Earth’s atmosphere. It will last not very long and I think we will all shed a tear because it’s been a 30-year experience, not only with the spacecraft, but with each other,” Larry said.

“For me I think in particular there’s a lot of excitement in this having been so successful and ending on such a successful note but a lot of fear and concern about what the future holds,” said Jason. “We all developed sort of a natural feeling that we were on the spacecraft,” Larry said.

“This has been one of the cornerstones of NASA’s unmanned space program for the better part of the last two decades and it is very unnerving to think about what the field is going to be without Cassini,” Jason said.

When Cassini, the craft that has spanned generations of researchers makes its final plunge, Larry and Jason will be together for the end of a journey they started on nearly 30 years ago without even realizing it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.