Cassini Researchers Say Spacecraft's Saturn Death Finale Is Bittersweet

After decades of planning and analysis, NASA’s Cassini mission is nearing its end. The spacecraft itself has been traveling space for nearly 20 years, the first seven of which were spent in transit to Saturn and the final 13 spent in orbit around the gas giant.

Next week the mission will come to an end when Cassini plunges into the planet’s thick atmosphere and sends back data until it burns up like a shooting star would in Earth’s atmosphere. For those who have been with the craft since its earliest stages, the end is bittersweet.

“I think there are three feelings. Probably the simplest is ‘Job well done,’ because this was a mission that exceeded by a mile in every possible measure the scientific promise that originally got this thing funded, built and launched,” Jonathan Lunine, the director of Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, who has worked on Cassini for 34 years, told International Business Times. The second and third emotions? Sadness and a feeling of “What next?” Lunine said.

On Sept. 15, the day of the finale, Lunine will be at the California Institute of Technology with the rest of his project science team. Instead of everyone gathering at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the gathering was moved to CalTech due to the sheer size of the crowd. Mixed emotions will be shared among the hundreds of scientists, researchers, engineers and others who have had a hand in making Cassini the historic and groundbreaking mission it has become.

“Once the last flyby of Titan occurs that puts Cassini on the collision course with Saturn there’s really nothing else to be done. Its fate is sealed so we’re just going to watch it from a place where we can all be together,” Lunine said.

One face will be missing from that crowd though. Jeff Cuzzi, a ring specialist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, who was part of the Cassini mission before it was even officially named, will be traveling when Cassini makes its final plunge. “I’ll be thinking of the spacecraft going in as I fly,” he told IBT.

While the end of the mission is sad, it’s also the start of a new part of research about Saturn. Even though Cassini won’t be sending back new information on a regular basis, there is still plenty to sort through. “There are more chapters yet to be written and that has to do with analysing and interpreting,” said Cuzzi. As for how he feels about the mission’s end, “It’s just a great sense of satisfaction and reward.”

“These discoveries leave us with a lot to do and for some of us the big questions are when we’re going to be able to do that,” said Lunine. The teams are funded for another year, so they have some time to sort through the the data. “There’s a lot more work to be done,” Cuzzi confirmed.

“Cassini was always central in my heart and there will be a hole there when Cassini goes away,” Lunine said. But he’s already working on a proposal for further research. As part of NASA’s New Frontiers program Lunine has proposed further research of possible life on one of Saturn’s moons Enceladus. He’ll find out in November whether or not his proposal will be considered further.

As connected researchers feel to Cassini there comes a time in every mission when the craft will run out of fuel. Even the Voyager craft that just celebrated 40 years of travel will one day see their final days.

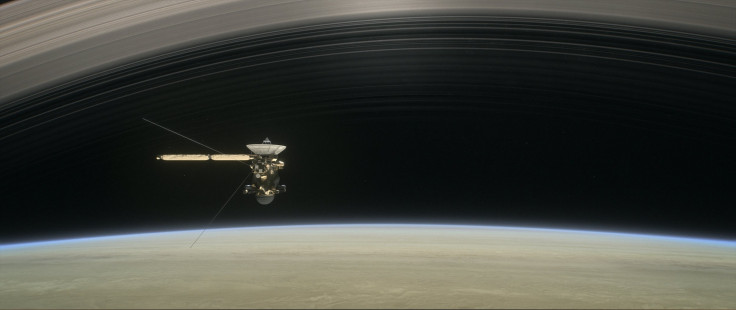

But Cassini’s finale has been a long time coming, weeks of final flybys and data correspondence have been built up to the fiery plunge. Even the plunge itself will happen in quite a spectacular way. But disposal in the very planet that has been the craft’s focus for the last 13 years wasn’t always the plan.

“It was always a plan, because NASA had to have a disposal option for Cassini,” Lunine explained. “There were several options that were considered, that was one of them. Another was to actually use Titan’s gravity to fling Cassini out of Saturn orbit and send it somewhere else,” Lunine explained. That “somewhere else” would have been out to Neptune or Uranus or back toward Jupiter, both of which would have required a lot of continual work from NASA.

But burning Cassini up in Saturn’s orbit was an option that offered scientific data that researchers would have never gotten otherwise, while disposing of the craft so that it wouldn’t contaminate any of the moons around Saturn that could potentially host life. “This was really the most practical,” Lunine said of the option to burn Cassini up in Saturn’s atmosphere. “It’s given us a kind of a whole new mission over these last six months or so.”

“We really have to stop for a moment and recognize that it was the engineering, extremely high- level engineering talent, that made this mission possible and made it possible for Cassini to do things that were never really planned before,” Lunine said.

“[The] challenge for the engineers was to design and build a spacecraft to allow all this to happen,” Cuzzi added. A challenge they rose to as the wealth of data left from the mission proves.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.