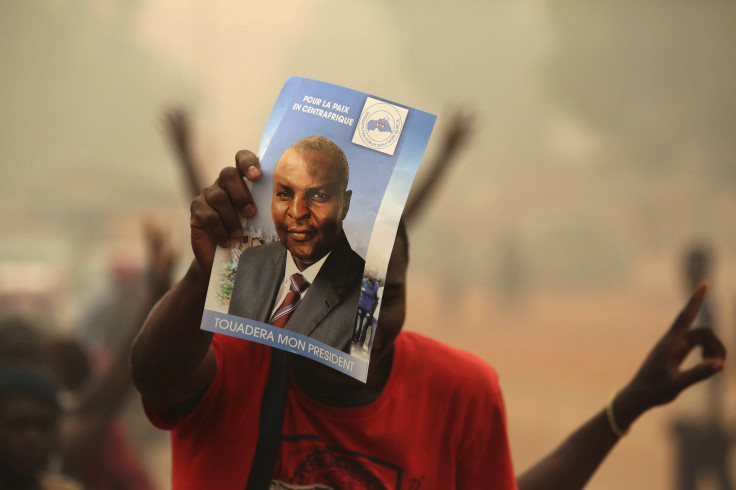

Central African Republic’s New President Touadera In Uphill Battle Against Warring Muslim, Christian Militias

As the Central African Republic’s new president, Faustin-Archange Touadéra, took the oath of office Wednesday in the capital, Bangui, he made lofty promises to rebuild a country shattered by civil war that exploded between Muslim and Christian militias more than three years ago. The former math teacher and prime minister swore to disarm fighters on both sides of the conflict, “preserve peace” and reunify a divided population.

Touadéra's presidential inauguration marked the final chapter of the political transition that began after the predominantly Muslim militia known as Séléka seized power from President François Bozizé, a Christian, in late 2012, which triggered a vicious tit-for-tat cycle of sectarian violence. Central Africans are eager to put the years of bloodshed behind them, but political and economic analysts said the odds are stacked against Touadéra, who now must form a credible administration, maintain peace in the city centers and reassert control over the rest of the nation, before he can begin reviving a flagging economy.

“The root of the violence is the politics in this country,” said Christopher Day, assistant professor of political science and African studies at the College of Charleston in South Carolina, who has conducted research on the Central African Republic. “When you have a population that’s p----- off and armed, if it’s going to be business as usual. I fear for peace and stability.”

After toppling Bozizé’s administration, Séléka leader Michel Djotodia took control for nearly 10 months until eventually ceding power amid international pressure to form a transitional government. Catherine Samba-Panza was selected by Parliament as the interim president in January 2014 to steer the former French colony to democratic presidential elections, which were finally held Dec. 30 last year. Touadéra emerged as the surprise winner out of dozens of candidates in a runoff vote Feb. 24, with nearly 63 percent of the ballots cast. Part of his popularity stems from his record as prime minister, from 2008 to 2013, during which time he ended decades of unpaid government wages by paying civil servants through direct deposits to their bank accounts.

However, the transitional government and regional peacekeepers have struggled to halt fighting nationwide between Séléka rebels and the mainly Christian anti-balaka militias. It’s a war that the French government has said has put Central African Republic “on the verge of genocide.” Some 400,000 people have fled their homes in Séléka-controlled areas, while another 460,000 have sought refuge in neighboring countries.

The French military, which launched a mission in Central African Republic in December 2013, has managed to restore some security to Bangui and other urban cities in the south. But armed groups operate freely in the vast north and have even established de facto tariffs. Taxation and customs were once a major source of revenues for the government that have been hijacked by militias in many parts of the small, landlocked country.

To make matters even more difficult for Touadéra, after he was sworn into office Wednesday, France confirmed it will end its military intervention in Central African Republic this year. France had around 2,500 troops deployed in the country at the peak of Operation Sangaris, supporting about 10,000 United Nations peacekeepers. Some 300 French troops will remain there, along with the regional peacekeeping forces.

"Of course everything is not resolved but we can finally see the country emerging from a long period of trouble and uncertainty,” French Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, who attended the presidential inauguration, said at the M’Poko airport in Bangui, according to Agence France-Presse.

Touadéra now faces the immediate challenge of maintaining the same level of security in major cities without France’s support. From there, it’s an uphill battle to secure the entire country. He must push a disarmament and demobilization program before national dialogue can be renewed between the warring factions, which have alienated parts of the nation from the central government in Bangui.

“The elections gave France the opportunity to book it and leave on a high note, but that means the window of opportunity for President Touadéra is that much narrower,” said J. Peter Pham, director of the Africa Center at the Atlantic Council, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. “If he’s allowed to fail, it could very well mean the carving up of the country.”

Once a stable ceasefire is put in place, state authority is restored and a reconciliation process is in motion, Touadéra’s government can begin revitalizing the economy, which has suffered immensely as a result of the ongoing conflict. The Central African Republic saw a 36 percent drop in its gross domestic product in 2013. The economy has slowly clawed back since then, but the agricultural sector — the chief contributor to GDP — is still grappling and the government is struggling to raise revenues.

“It’s a balancing act in terms of security, and he must engage in a titanic economic recovery effort,” Central African economist Achille Nzotene told AFP news agency Wednesday.

Despite his popularity among Central African Republic voters, Touadéra could also lose their good faith if he fails to set up a credible and inclusive administration. Observers said previous governments, including the transitional one, have recruited the same, small, elite group in the predominantly Christian nation who cater to their own interests in Bangui. This has long marginalized the Muslim minority population who primarily reside in the north and has given way for thousands of fighters to rise up in revolt. Touadéra, who served as premier in Bozizé’s administration, now has the power to address this core issue by diversifying the recruitment of public officials.

“My main concern looking forward is whether or not he repeats the same pattern of just recycling elites,” said Day, of the College of Charleston, who recently traveled to the Central African Republic. “There are a very small number of elites and they seem to change places like musical chairs. That’s been the heart of the country’s problem.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.