CEOs Must Not Ignore Their Divorces And Shareholders Must Start Caring Too: Stanford Business School Study

CEOs must get real about their romantic relationships and the impacts of divorce, according to a Stanford Graduate School of Business study linking CEO divorces, executive pay and early retirement.

Published on Tuesday, the report -- entitled “Separation Anxiety: The Impact of CEO Divorce on Shareholders” -- warned shareholders that divorces may have drastic, regular and predictable impact.

Stock values may fall sharply on speculation about a CEO’s spouse obtaining majority control through stock transfers, for example.

Shares fell 2.9 percent on such speculation in the divorce of Harold Hamm, CEO of Continental Resources Inc. (NYSE:CLR) in March 2013, even after the company reassured investors in a news release that the divorce wouldn’t materially impact the business.

“A CEO with a significant ownership stake in a company might be forced to sell or transfer a portion of this stake to satisfy the terms of a divorce settlement,” the report reads.

If shareholders like the CEO, and he loses some ownership, shares may dip. If shareholders don’t like the CEO, and a spouse grabs some equity, shares may actually rise.

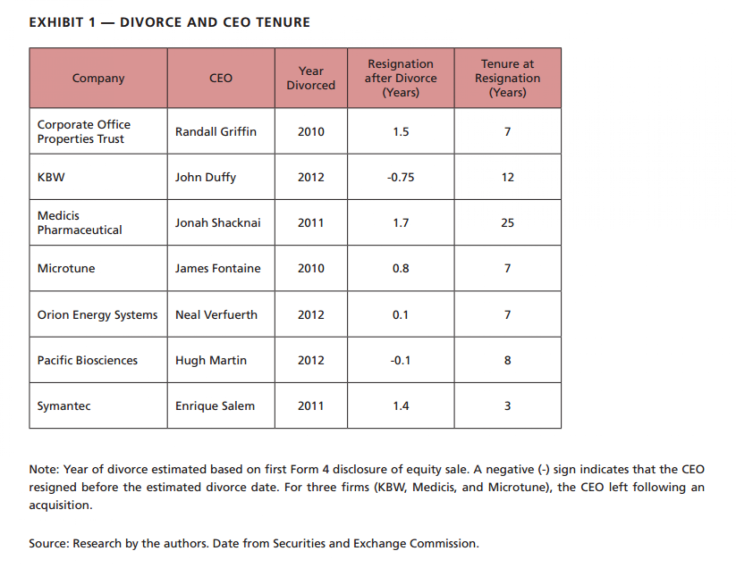

In other cases, the “distraction” of divorce can spur early retirement for an unhappy CEO.

The study’s authors cited the case of former the Procter & Gamble Company (NYSE:PG) CEO Alan "A.G." Lafley, who stepped down a year before his promised term to shareholders, in 2009, on divorce and other romantic grounds.

In a remark at the time, one P&G analyst said: “It was done rather abruptly… We had been saying A.G. had committed to deliver the decade, and the decade was one more year.”

Study authors acknowledged, however, that they were "unaware of rigorous research on the relation between divorce and CEO retirement.”

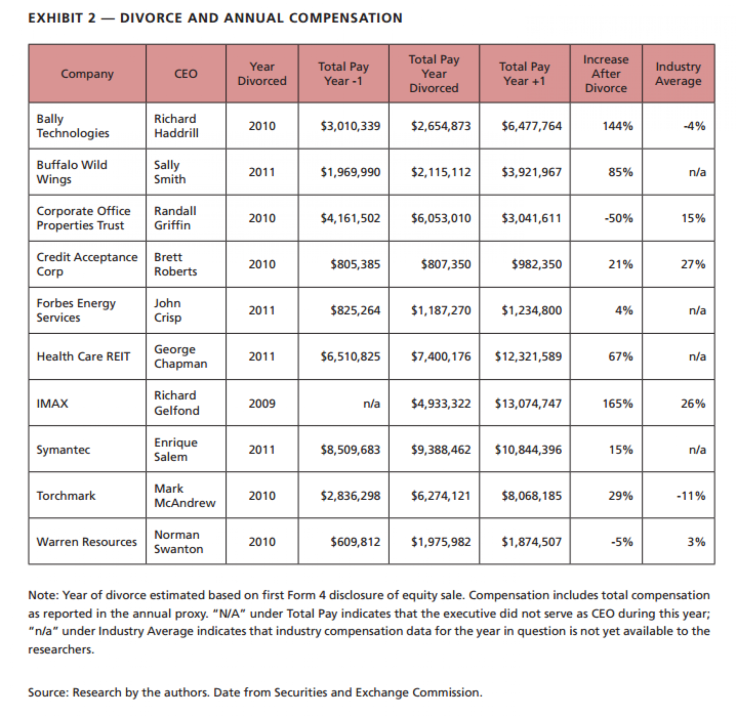

Sometimes, too, CEOs are paid more or less following a divorce, and may tweak their business strategy as a result. In particular, they may make riskier or more cautious decisions.

Executive decision-making may become more prudent if a CEO loses personal funds through a divorce, keeping most of his wealth through company stock or other equity. Since he’s more personally exposed to the company’s market value, he might “reject promising but risky investments.”

Conversely, a daring CEO could take riskier decisions if personal poverty pushes him to increase the value of his company equity for personal gain, whatever the consequences.

“A CEO in this situation might approve higher-risk investments to boost the value of his or her remaining equity holdings following divorce,” the researchers wrote.

They cited previous research on CEO compensation and divorce, which amounts to “modest evidence” that CEO pay is boosted after a marriage fails.

The authors pose provocative questions at the end of their two-page report:

Should company boards provide financial incentives to leave a CEO’s net wealth untouched post-divorce, to avoid erratic decision-making? Or does that represent an unfair cost to shareholders?

Should companies force disclosures of CEO divorce, which isn’t now legally mandated except in obscure regulatory filings known as Form 4s?

In other words, the researchers said, “Is divorce a private matter, or should companies disclose this information to shareholders?”

Below are two charts from the report that use small and selective samples, but which make the case for the authors.

News Corp.'s (NASDAQ:NWSA) beloved Rupert Murdoch emerged unscathed from his divorce, with little material impact on his influential media conglomerate, the authors noted up top.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.