China's Social Media Crackdown Likely To Continue, A Clear Indicator Of Future Direction Of President Xi Jinping's Administration

Following a wave of arrests of prominent microbloggers on China’s Twitter-like Weibo, there has been widespread speculation on what the Chinese government is hoping to achieve, and how far it's willing to go to that end. The ChinaFile asked a few political commentators to weigh in, and discuss what can be expected from the ordeal.

It seems no one is immune to the crackdown. Charles Xue, a Chinese-American multi-millionaire investor and one of the most popular bloggers on Weibo, appeared on China’s state TV in handcuffs on Sunday, and engaged in what was known in Maoist days as “self-criticism,” an admission that he was irresponsible in spreading information online.

"My irresponsibility in spreading information online was a vent of negative mood, and was a neglect of the social mainstream," Xue said.

In many ways, while the current sweep represents a new systematic censorship of Internet opinions and microblogging, the tactic is not a new one. The treatment of Charles Xue is comparable to that of Ai Weiwei in 2011, when the well-known artist was held for 81 days without charge, according to Jeremy Goldkorn, the founder and director of Danwei, a research firm that tracks Chinese media and Internet. Xue might have even suffered less in comparison.

In response to a statement from Lu Wei, the director of the State Council’s Internet Office, which said that the Chinese Communist Party must capture the new battlefield of public opinion in the Internet era, Goldkorn wrote:

“If the Internet had been around a hundred years ago, Lenin would perhaps have written something like the lines above. The pushback against Big V’s is nothing new, it’s just the latest example of the authorities’ tried and tested methods of control," said Goldkorn.

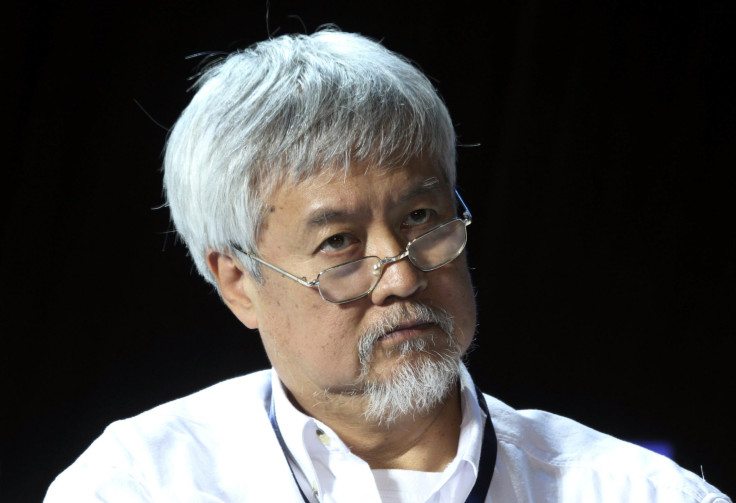

Aside from the Russians, the campaign may have a role model closer to home, according to Xiao Qiang, the founder and editor-in-chief of China Digital Times. The move is a clear manifestation of President Xi Jinping’s political line and the direction of the central administration under his leadership, that is, an attempt to return to Maoist mass movement methods to control and mobilize the society, in order to retain firm control, Xiao added.

Commentators agree that China is unlikely to ease off the pressure on Internet opinions. Xiao suggested that this is just the beginning.

“I’d say that the current rumor crackdown is just the tip of a very large policy iceberg,” said Rogier Creemers, the editor of the China Copyright and Media website and a China expert. “…the situation on China’s Internet we see today: enormous commercial developments on the one side, and a government that is trying to regain control through increasingly harsh methods on the other.”

With numerous high-profile detainments like Xue's, and the announcement of the new defamation charge, which threatens any Internet user whose Weibo posts are viewed by more than 5,000 readers with jail time, it seems the Chinese government will succeed in holding onto control for a while longer, but that may not be good news even for China’s leaders, according to Vincent Ni, the Europe correspondent at Caixin Media.

“But if no one is willing to speak out online for fear of being punished, and most official information is neither transparent nor reliable,” Ni said, “what will most likely happen is the spread of more offline rumors that further disrupt social order.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.