Is Climate Change Real? Here's Why Some Americans Still Have Doubts

Wendy Billiot isn’t sure how she feels about global warming. She knows local scientists say rising sea levels will eventually sink her community in coastal Louisiana, but to her the biggest problem is here and now. Seated at her kitchen table, she smooths a laminated map of Terrebonne Parish and points to wetlands that are rapidly disappearing, the result of decades of dredging by oil and gas companies and ill-conceived levees along riverbanks.

“Sea level rise is a hard sell here. People down here don’t want to hear about global warming,” she explains. “They’re not sure they believe in it. And I’m not even sure where I stand on it, to be honest. What I see with my eyes is the water coming in because of wetland loss. I’ve watched it deteriorate over 35 years.”

Thousands of miles away, in drought-stricken California, Jack Castro is certain that humans are not responsible for rising temperatures. As the city manager of Huron, a tiny farming town near Fresno, he sees firsthand how California’s vanishing snowpack and rains are decimating fields and depleting municipal supplies. “Global warming is a different issue,” he says about the city’s water shortage. “This is just a cycle.”

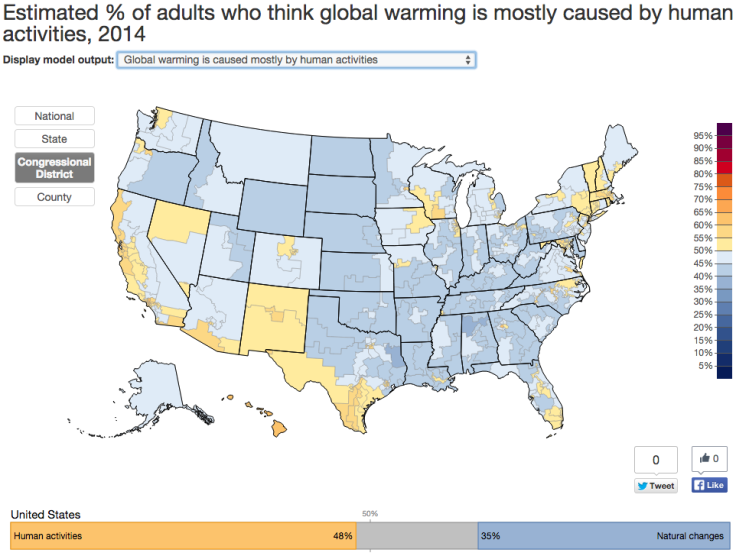

Billiot and Castro aren’t outliers when it comes their opinions on climate science. While more Americans are convinced of climate science today than five years ago, a significant portion of the country is still doubtful. Sixty-three percent of American adults believe the atmosphere is heating up, compared to 57 percent in 2010, researchers from Yale University found in a survey released this week. But only 48 percent of adults believe humans are mostly to blame for global warming, about the same amount as in 2010.

The division exists even amid the heightened warnings that burning oil, coal and natural gas for energy is leading to unprecedented emissions of greenhouse gases. This, in turn, is raising the planet’s surface and ocean temperatures, causing sea level rise, erratic weather patterns and a host of other effects that over time will endanger communities and disrupt food and water supplies, 97 percent of the world’s climate scientists agree.

Much of the confusion among Americans has been sowed by fossil fuel companies and their supporters, who plow millions of dollars each year into lobbying efforts and advocacy campaigns in an attempt to keep the world reliant on carbon-rich energy. Organizations that promote climate denialism received nearly $560 million in untraceable donations from 2003 to 2010, a Drexel University study found.

It doesn’t help when mainstream news outlets skew the facts: On Fox News alone, more than 70 percent of the channel’s climate coverage in 2013 contained misleading statements, the Union of Concerned Scientists, an advocacy organization, reported last year. For CNN and MSNBC, 30 percent and 8 percent of climate-focused segments were misleading, respectively.

Complicated Questions

Yet Americans' views on climate change are also powerfully influenced by personal forces, including religion, political affiliation and community. In coastal Louisiana, for instance, practically every family has a member who works for an oil and gas company or a related business. Climate change doesn’t just evoke concerns of coastal erosion -- it also raises complicated questions about how the economy will fare if the world no longer consumes fossil fuels.

“The debate over climate change right now is not about carbon dioxide or climate models. It’s about values and worldviews,” says Andy Hoffman, who directs the Erb Institute for Global Sustainable Enterprise at the University of Michigan and authored a new book, “How Culture Shapes the Climate Change Debate.”

"We usually try to understand things through the filter that we have,” he says.

As with any hot-button issue, those cultural filters differ within groups of friends and families. Katharine Hayhoe says she learned this firsthand shortly after marrying her husband, Andrew Farley. Hayhoe is an atmospheric scientist, but the couple, both devout Christians, didn’t discuss where they stood on climate change until after tying the knot.

“Before I moved to the University of Illinois [from Canada] for graduate school, I had never met anybody who didn’t think climate change was real,” she recalled in a recent radio interview with RadioWest in Salt Lake City. “He had never met a Christian who shared his faith who did think climate change was real. And, because of our mutual naïveté, we never even thought to bring it up before we got married.”

Hayhoe said Farley “really felt you can’t be a Christian and think that this is real. This isn’t something that Christians believe.” For some evangelicals, the notion that humans can dramatically alter God’s creation is sheer hubris. If the planet is actually warming, then it’s likely part of God’s divine plan for the Earth, the thinking goes.

Hayhoe eventually convinced Farley of the science through continuous discussions, and in 2009 the couple co-authored "A Climate for Change," a book that presents climate change through a faith-based lens. Today she is a prominent voice on the subject and directs the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University in Lubbock. Last year, Time magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people in the world. Farley is an applied linguistics professor at Texas Tech and the pastor of a local evangelical church.

When speaking to Christians, Hayhoe said she cites the belief that God gave humans the freedom to make their own decisions, both good and bad. “And when we make bad decisions, there are consequences,” she said in the radio interview. With climate change, “We’re seeing the result of the decisions that we’ve made.”

Beyond religion, the most influential factor in shaping a person’s climate beliefs is political party affiliation. “That’s the No. 1 demographic variable,” Hoffman says.

A variety of surveys in recent years consistently show wide margins of opinion between Democrats, Republicans and political independents. A Pew Research Center survey, for instance, found only 25 percent of self-identified Republicans said they considered climate change to be a “major threat,” while 65 percent of Democrats gave that answer. In a recent Gallup poll, 74 percent of college-educated Republicans said they believed the media generally exaggerate the threat of global warming, while only 15 percent of college-educated Democrats gave the same response.

Some political conservatives are wary that accepting climate science implies agreeing to liberal politics. Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, a Republican contender in the 2016 presidential race and a climate denier, warned that adopting solutions proposed by global warming “alarmists” would mean “government control of the energy sector, and every aspect of our lives,” he said in a video interview with the Texas Tribune.

'The Problem Is Al Gore'

Republicans also bristle at the idea of siding with prominent Democrats like former Vice President Al Gore, who became one of the world’s loudest voices on climate action after his 2006 documentary “An Inconvenient Truth” thrust climate change into the public spotlight. In March, Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., who thinks climate change is real, blamed Gore for making it difficult for Republicans to get behind the issue. “The problem is Al Gore has turned this thing into a religion,” Graham said at an event at the Council on Foreign Relations.

The politicized nature of America’s climate debate “has marginalized many moderates and conservatives from engaging in this discussion,” says Jay Faison, a Republican and self-described serial entrepreneur.

Faison founded the ClearPath Foundation in December, adding to the small but growing number of right-leaning groups that are pushing for progress on climate change. Part of ClearPath’s mission is to restore Republicans’ environmental legacy, Faison says, noting that Theodore Roosevelt was one of the earliest presidential advocates of conserving and protecting America’s land and wildlife. Ronald Reagan helped push the world to adopt the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which required the phasing out of ozone-depleting chemicals.

“Environmental protection has drifted over time from a topic that once united all Americans … to one that divides us as a symbol of our opposing political parties,” Faison says. Rather than dispute the science of climate change, “Let’s debate whose solutions for clean air and water, energy independence, innovation and job creation are better.”

Hoffman says the emergence of voices like Faison’s and Hayhoe’s will be critical for shifting the climate debate away from doubt and toward action. “If you want to reach evangelical Christians, you need to have evangelical Christians start to speak out about this,” he says. “And we need more messengers from the ideological right.”

For everyone else, he cautions against trying to convince climate doubters by waving complex data sets or pointing to thick international climate reports. “If you keep hammering people with more data, and they’re connecting this with their personal identity, they’re going to dig their heels in harder,” he says. “Beating people into submission is not a way to get them to accept the science. You need to understand what is causing them to resist it.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.