Currency Wars 2013: How Far Can The Japanese Yen Fall With Haruhiko Kuroda Taking The Bank Of Japan Helm?

The yen has been slipping and sliding, down almost 10 percent this year, thanks largely to calls for new stimulus from Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. As Japan's new central bank governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, takes the helm this week with a pledge to end the nation’s 15 years of deflation, it raises the inevitable question: How low can the yen go?

Potentially a lot lower, analysts say. But the Japanese yen won’t stay cheap forever.

Since mid-November, when Abe called for bold fiscal expansionary and monetary easing policies in his election campaign, the yen has depreciated nearly 18 percent.

The Japanese economy has fallen to No. 3 from No. 2, behind the U.S. and China. A weaker yen makes Japan's goods cheaper abroad, but this could cause China and the other countries to respond in a tit-for-tat manner. Earlier this month, China’s Commerce Minister Chen Deming said he’s concerned at the risk of competitive devaluations and warned that emerging markets will be the ones left to pay the price for currency wars.

A Profound Monetary Regime Shift

A dramatic shift toward more simulative fiscal and monetary policy is underway in Japan.

The Japanese government has put together a large fiscal stimulus program worth approximately 20 trillion yen ($116 billion), or 4.2 percent of gross domestic product, of which about 13 trillion, or 2.7 percent of GDP, was included in the FY12 supplementary budget that included about 5 trillion yen of public works spending.

Monetary policy is also set to take a more aggressive turn.

Kuroda has declared a mission to reach the bank's target of 2 percent inflation "as soon as humanly possible." During his inaugural press conference on Thursday, Kuroda rebutted doubters who predict his efforts will fail as he prepares to strengthen monetary stimulus.

Kuroda's predecessor, Masaaki Shirakawa, is among those who say it can't be done, at least not with the tools at hand. On his way out, Shirakawa gave his final warning that quantitative easing cannot solve deep structural problems and is like "punching air" if firms refuse to borrow.

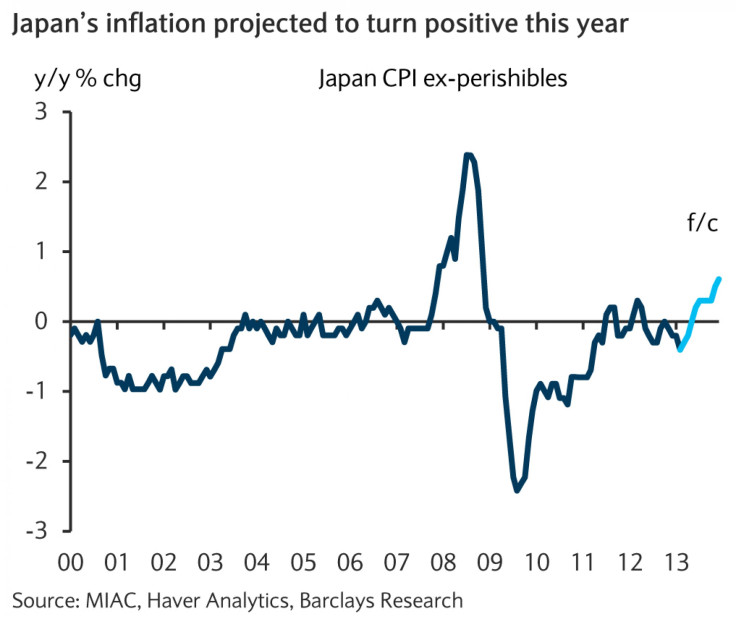

Barclays economists expect inflation to move into positive territory in Japan this year, but see a sustained move to 2 percent within two years as difficult to achieve.

Central-bank watchers think the BoJ could unveil monetary policy erasing measures as soon as Kuroda’s first policy meeting in April.

How Low Can The Yen Go?

Jose Wynne, head of global FX strategy at Barclays, expects USD/JPY to peak at around 103 a few days after the central bank unveils its plan to achieve its 2 percent inflation target, early in April, and to trade sideways at around those levels in the next six months. On Thursday, the U.S. dollar traded in upper 94 yen range.

Yen weakness cannot be a one-way story where the yen weakens and then stabilizes at a lower level, Wynne said. For that to happen, markets have to believe that inflation in Japan will accelerate beyond the target by a significant amount, something he does not expect to see.

“Instead, we believe this is a story of overshooting, where the yen temporarily weakens to later come back,” Wynne said in a note to clients.

While it is feasible to achieve the 2 percent inflation target by further weakening the yen, this policy will soon face practical and political constraints.

At a USD/JPY level of 110, this policy would have managed to devalue the U.S. dollar value of wages by 45 percent since the experiment started last November, according to Wynne. “This may be good for job creation, but not for workers already employed, accounting for almost 96 of the labor force,” he said.

Together with workers, importers would bear the cost at the expense of exporters. The pain imposed by a much weaker yen could become intolerable for some.

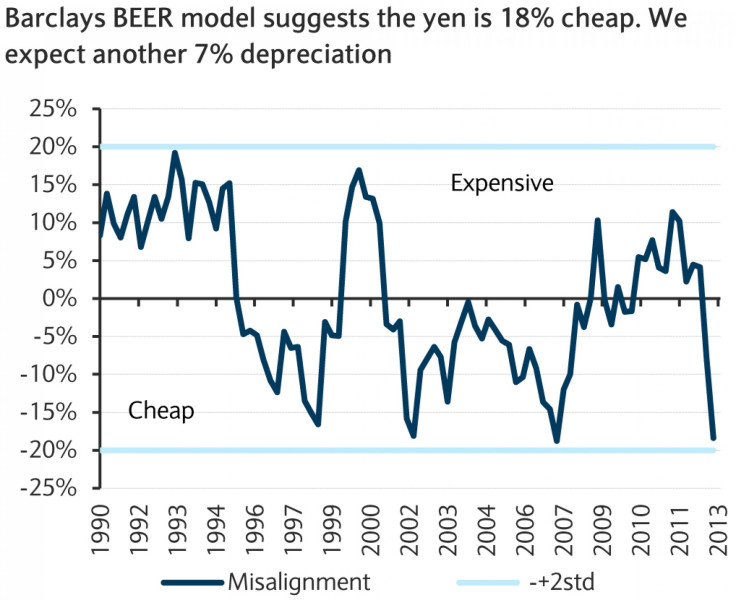

The chart below provided by Barclays shows that the yen reached such cheap levels before, in 1997, 2002 and 2007. This makes current levels (18 percent cheap) a risk Barclays economists think the BoJ could easily justify in its battle against low inflation.

Furthermore, those levels were never enough to generate inflation in the past although, granted, the yen was never kept low for long enough. “This makes us confident that the government can push the FX lever some more,” Wynne said, adding that the Japanese government can justify driving the yen as much as 25 percent below fair value, which takes USD/JPY to 103 -- 5 percent over the yen’s historic extreme lows.

However, the USD/JPY cannot stabilize at a high level without accelerating inflation above 2 percent. This implies that, sooner or later, the BoJ will have to absorb the liquidity to contain inflation if USD/JPY remains high, bringing the yen closer to fair value.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.