CyArk Uses 3D Laser Scanning To ‘Digitally Preserve’ World Landmarks; Includes Babylon, Sydney Opera House, The Titanic [PHOTOS]

Years of wear and tear have significantly altered some of our World’s most recognized ancient landmarks. (Did you think the Great Sphinx of Giza’s missing nose was cosmetic?)

And even the newer ones like Mount Rushmore or the Sydney Opera house are sure to acquire some dings and chips over their lifetimes.

That’s why CyArk, a California-based nonprofit that makes digital copies of various historic structures and sites using 3D laser scanners, has vowed to digitally document more than 500 of our world’s most significant manmade and natural landmarks -- before erosion, earthquakes, floods and human hands get the best of them.

"If you can't physically save something, your next best thing is to digitally preserve it,” Ben Kacyra, who co-founded CyArk with his wife, Barbara, in 2003, said at the conference.

“While there isn’t enough time or money to save all these sites physically, we have the technology to digitally preserve them," he said. "By doing so, we will ensure that these treasures are available for appreciation and study for years to come.”

CyArk's team announced its initiative to scan hundreds of heritage sites around the globe Monday at a conference in London.

Based in Oakland, Calif., CyArk has already scanned more than 100 of the world’s most recognizable monuments, including Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, Mexico’s Chichén Itzá, Mount Rushmore and Chile’s Rapa Nui. They’ve also mapped some more unconventional sites, like the wreck of the Titanic and John Muir’s birthplace in Scotland.

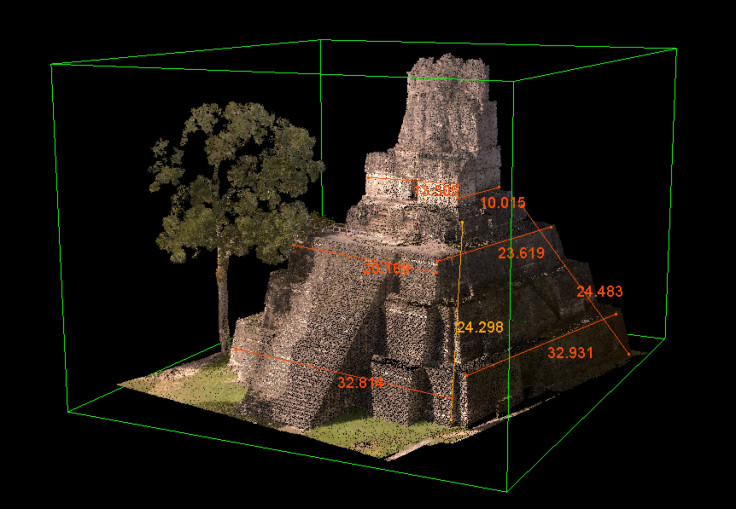

The 3D-scanned projects can be as large as 10 terabytes. The technology works by sending pulses of light onto the surface of a structure. The system measures how long it takes for the light to return and translates this information into X, Y and Z coordinates. It then creates a 3D model of the structure in front of it using millions of these high-resolution points.

The entire process takes just seconds, and is accurate to within 2 to 6 millimeters, according to WaayTV.

“The scanners, although they are 3D, operate like a camera -- what they see is what they can capture,” Kacyra explained. “The scanner is like a large camera sitting on a tripod. You need to take it round the building. It will create a 3D model automatically once you go all around.”

CyArk keeps its digital copies of historic landmarks in a highly secured bunker 220 feet below the ground in Pennsylvania. The location, called Iron Mountain, houses other precious cultural collections, like the music of Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley and iconic movies like E.T. and Jaws.

“We’re proud to play a role in preserving and facilitating access to these important heritage sites,” Harold Ebbighausen, president of Iron Mountain, told reporters, according to WaayTV.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, includes 981 sites on its World Heritage List that are considered to have “universal value.” To be included on the list, a site has to meet certain criteria. For one, a site must “represent a masterpiece of human creative genius.”

Some of these, like the Royal Tombs at Kasubi in Uganda, have already been scanned and documented in 3D by CyArk.

“These sites happen to represent a part of our collective memory as a human race,” Kacyra said. “Losing our collective memory is equivalent to losing a very important part of who we are. They teach us about the past and they also throw a light forward for the future. They are extremely important for us culturally and especially for our children, who are growing up to look back and say, ‘Where did we come from?’”

According to The Associated Press, Kacyra said he was inspired to start CyArk after the Taliban shattered a pair of giant Buddha statues in Afghanistan in 2001.

The nonprofit will take suggestions through its website for future projects.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.