Defiant Mayor Bloomberg Vows To Appeal ‘Stop & Frisk’ Ruling

New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has vowed to appeal a Monday ruling by a federal judge that stated that the NYPD’s controversial “stop and frisk” policy violates its targets’ constitutional rights because its implementation relies on race-based discrimination.

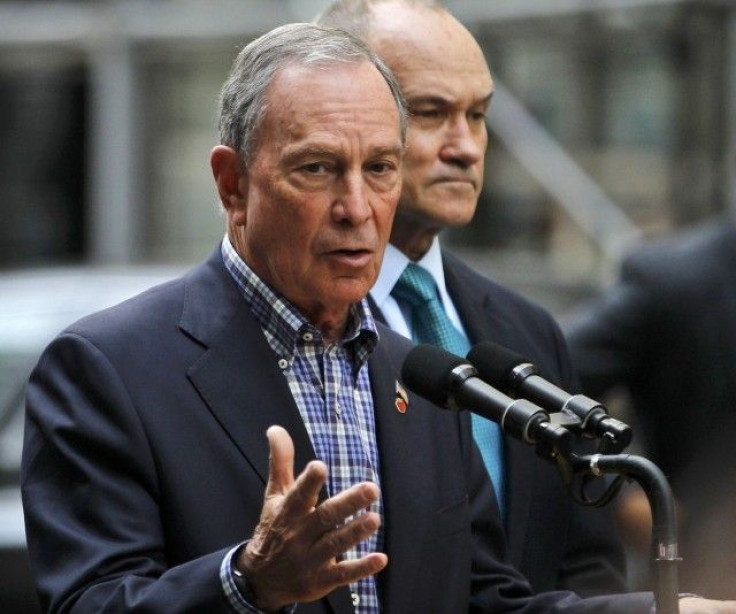

In a defiant press conference at City Hall on Monday afternoon, Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Ray Kelly defended the practice and sought to rebut criticisms of the “stop and frisk” regime made in U.S. District Court Judge Shira Scheindlin's 195-page ruling and by a wide range of advocates, city residents, and other critics.

“This is a very dangerous decision made by a judge that I think doesn’t understand policing or what is allowable under the Constitution as determined by the Supreme Court,” Bloomberg said.

Meanwhile, the Center for Constitutional Rights hosted a simultaneous press conference featuring a number of plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the city over “stop and frisk” that resulted in the Monday decision. The mood there was decidedly upbeat as civil rights advocates, community leaders and the plaintiffs themselves praised the ruling, calling it an important first step toward reigning in what they see as the NYPD’s discriminatory practices.

Bloomberg and Corporation Counsel Michael Cardoza, the city’s top attorney, repeatedly said at City Hall that the city will appeal the decision and ask for a stay of the accompanying order, which requires the implementation a variety of reforms including the appointment of an independent monitor of some “stop and frisks” and requiring some police officers to wear cameras on the beat.

“As soon as we determine it’s legally appropriate to take the appeal, we’ll certainly ask the 2nd Circuit to [stay the order],” Cardoza said, adding later that, “As soon as we have the legal right to seek an appeal and to say ‘judge, stop this order,’ we will do so.”

Cardoza clarified that such a move would most likely come after the independent monitor “directs us to do something specifically.”

Bloomberg and Kelly both spent much of the lengthy address vehemently defending the policy, saying that it has driven crime down in New York and saved hundreds of lives. They went on to assert that police officers do not engage in racial profiling but instead stop black and Hispanic males at highly disproportionate rates due to the fact that a disproportionate percentage of crimes in the city are committed by and against these populations in poorer neighborhoods.

“What I find most disturbing and offensive about this decision is the assertion that the NYPD engages in racial profiling,” Kelly told reporters. “Last year 97 percent of all shooting victims were black and Hispanic and reside in the city’s lower-income neighborhoods … There were more police stops in neighborhoods with high crime because that’s where the crime is.”

As he has done repeatedly in the past, Bloomberg suggested that people who are not involved in public safety should not attempt to put themselves in the shoes of those who do.

“The public are not experts at policing. Personally, I’d rather have Ray Kelly deciding how to keep my family safe rather than someone on the street saying, ‘I don’t like that,” Bloomberg said.

Darius Charney of the Center for Constitutional Rights and many of the other attendees of his organization’s press conference rejected the arguments made by Bloomberg and Kelly.

“This is a historical and long overdue victory because what this court has confirmed today is something that many New Yorkers, thousands of New Yorkers, have long known,” Charney said. “It’s a recognition on the part of the court that what the city’s been doing for 15 years, really, is denying the existence of an unconstitutional practice.”

But the participants in the event emphasized that the ruling is only the first step in a long road toward reforming the NYPD’s practices and restoring public trust in law enforcement.

Leroy Downs, one of the plaintiffs in the case, was stopped by police officers on Staten Island in 2008, according to court testimony. He said the ruling was a positive result that he hopes will get the ball rolling toward an overhaul of discriminatory practices at the NYPD.

“We came to the table saying this is our experience, and we’re speaking on behalf of so many people across the city,” he said at the Monday press conference. “I’m hoping … we can really have some changes in the legislation and some real reform of ‘stop and frisk.’”

A “stop and frisk” is essentially a warrantless search of an individual in public who is deemed to be suspicious, likely dangerous, or potentially carrying a weapon by one or more officers. Bloomberg and Kelly, who refer to the practice as “stop, question and frisk,” have repeatedly cited it as being a key law enforcement tool and a major contributor to the sharp drop in violent crime New York City has experienced over recent years.

But many civil rights advocacy groups and privacy advocates assert that the practice constitutes an unconstitutional invasion of people’s privacy and that it unfairly targets black and Hispanic New Yorkers. Scheindlin’s ruling was the most significant win this camp has had thus far in the fight against the NYPD’s implementation of the policy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.