This Diamond-Laced Meteorite Could Be From Earth’s Long-Lost Planetary Sibling

Nearly a decade ago, an asteroid measuring 13 feet across exploded over the Nubian Desert in Sudan. The space rock, now dubbed 2008 TC3, didn’t leave any damage but the fragments that fell on the ground after that explosion could be the key to understanding the history of our solar system, particularly planets that faded away with time.

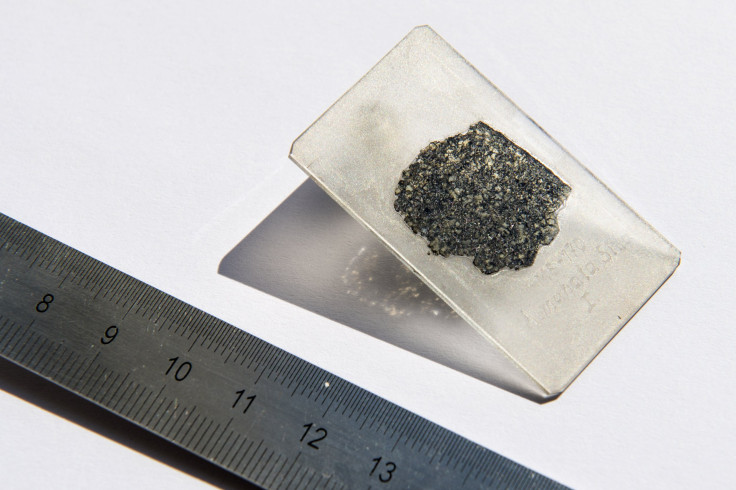

Our stellar neighborhood has eight main planetary bodies, but according to an international team of scientists, there could have been another planet in our backyard, one that might have been destroyed at infancy during the chaotic formation of the solar system or in the ensuing years. The group thinks these diamond-laced fragments — measuring one to 10 cm — belong to the same lost planet.

The researchers posited this theory after gathering and analyzing the asteroid fragments through transmission electron microscopy. They gathered the tiny pieces and cataloged them into Almahata Sitta, a collection of rare meteorites that often carry nano-sized diamonds.

Scientists believe most diamond-studded fragments like these form in various ways — shockwaves from the collision between parent body of the meteorite and other space objects, chemical vapor deposits or the pressure inside the parent body, just like diamonds on Earth.

In this specific case, scientists found the third one applicable. They determined materials like this could have only formed at pressures around 200,000 bar (2.9 million psi), something that could have only existed deep within a planet, one which would have been at least as big as Mercury or even Mars.

Their analysis also revealed that the fragments contained chromite, phosphate, and iron-nickel sulfides, chemicals or ‘inclusions’ that are commonly found in Earth-originated meteorites but were never observed in a space rock fragment before this.

"What we're claiming here is that we have in our hands a remnant of this first generation of planets that are missing today because they were destroyed or incorporated in a bigger planet," Philippe Gillet, one of the co-authors of the work, told the Associated Press.

Several theories and planetary models have suggested that during the first few million years of solar system’s chaotic formation, many infant planets existed, said a release from EPFL, Switzerland, one of the institutes involved in the analysis of the fragments. Some of these bodies were nearly as big as Mars and one of them, dubbed Theia, collided with Earth to throw our moon into orbit.

Rest either went on to form bigger planetary bodies or ended up being destroyed by the sun or ejected out of the solar system. This study backs that theory and "provides convincing evidence that the ureilite parent body was one such large ‘lost’ planet before it was destroyed by collisions some 4.5 billion years ago,” the authors of the study noted.

A paper titled "A large planetary body inferred from diamond inclusions in a ureilite meteorite" details the observation and analysis of the meteorites and is published in the journal Nature Communications on April 17.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.