Does Penn State Deserve NCAA Violations for Sandusky Scandal?

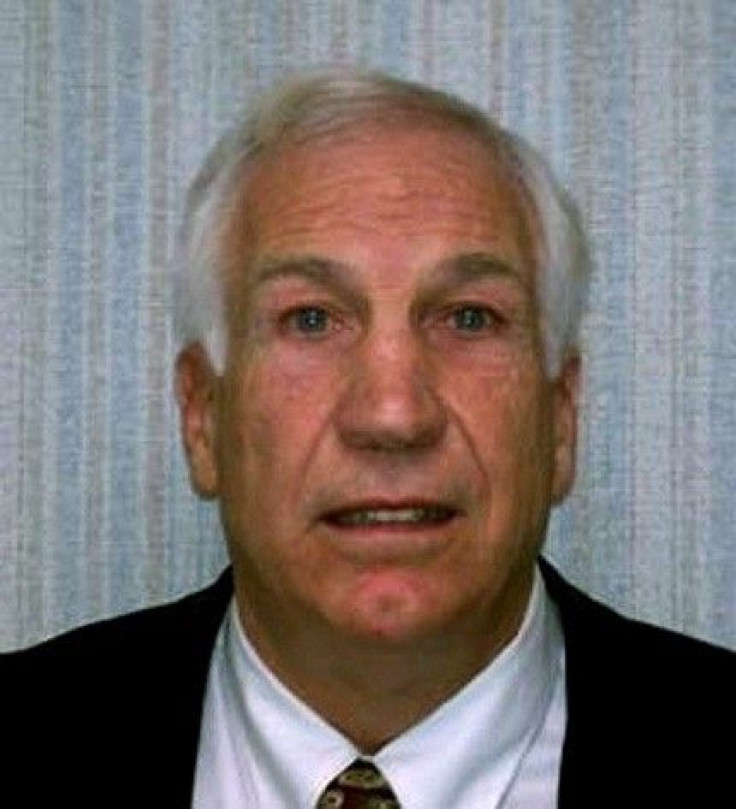

Last Friday NCAA president Mark Emmert informed Penn State that the organization would investigate the Jerry Sandusky scandal for possible rules violations.

Emmert said that the NCAA would look into the school's exercise of institutional control when dealing with allegations that a former defensive coordinator sexually assaulted children on the school's sprawling campus in State College.

The Pennsylvania attorney general's office alleges that Sandusky, who retired from the school in 1999, systematically preyed on young boys over an extended time period, including anally raping a 10 year-old boy in a Penn State locker room in 2002. He's been charged with 40 counts of abuse and faces up to 460 years in prison.

The scandal has dominated the headlines since becoming public knowledge on Nov. 6 and now has generated interest from the NCAA in whether the school violated the ethical spirit of the organization's bylaws.

But David Swank, the former Chairman of the NCAA's Infraction Committee, says that Penn State's issue is a criminal one and shouldn't concern the NCAA.

For the NCAA to get involved, there must be some violation of NCAA rules, Swank, the former Chairman of the NCAA's Infraction Committee, told the IBTimes. This is strictly a criminal manner. It's related within athletics, but it involves criminal conduct and not NCAA rules.

It's not their business (to get involved). Their business is dealing with athletic eligibility. Leave the rest up to the prosecutors.

The NCAA doesn't have one particular bylaw that Penn State violated, but the main argument against the school centers on what would be a lack of institutional control to handle the issues that came up.

The Grand Jury report on the Sandusky allegations revealed that the school had multiple opportunities to handle the allegations, but largely swept them under the rug. There were the 1998 allegations that Sandusky inappropriately showered with a young boy; the 2000 allegations that a janitor walked in on Sandusky performing oral sex on a young boy; and the disgusting case in 2002 of Mike McQueary walking in on Sandusky raping a young boy.

Sandusky was never formally charged of anything and instead suffered small slaps on the wrist. He had his football keys taken away, but still frequently worked out at Penn State and allegedly took young children to Penn State football games.

He even flaunted the penalty by organizing football camps on some of Penn State's other campuses.

It wasn't until 2008 when Sandusky was volunteering at a Pennsylvania high school that allegations were finally brought to police and an investigation into his behavior began.

The lack of action by Penn State officials has led to the dismissals of long-time coach Joe Paterno and school president Graham Spanier; with McQueary being placed on administrative leave.

The fact that so many high-level Penn State employees knew and did nothing should eliminate the idea of a lack of constitutional control, says filmmaker Thaddeus Matula.

Complete institutional control from what I'm reading, Matula told IBTimes. These things were known and nothing was done about it. When you have an institution that knows something of this nature, then there is institutional control.

Matula would know a bit about institutional control and the NCAA handing out violations. He's the director of the critically-acclaimed ESPN documentary, Pony Excess, the story of Southern Methodist receiving the death penalty in the 1980s.

SMU was one of the most dominant teams in college football in the 1980s -- in part through the spectacular running back tandem of Eric Dickerson and Craig James -- but it all came crashing down in 1987. The school was caught paying for players to come and play at the Dallas-area school and received the first-ever death penalty.

A select group of boosters, according to Matula, were trying to help out players of poor socio-economic backgrounds and couldn't stop themselves once the NCAA started to get involved. The school eventually decided to try to just ride it and stop the payments internally, but it backfired.

It started as guys thinking they were doing the right thing to help these kids out, he said. To let them have fun in the big city or to go out for pizza and then it got out of control.

But what you had at SMU pales in comparison to other NCAA football scandals in that all the money changing hands wasn't all that much. It's blown out of proportion because they got the death penalty.

The NCAA banned SMU from televised and bowl games for two years and essentially neutered the program for 20 years. The governing body has never used the penalty on a football program since 1987, but some have called for it to be used recently.

First there was the scandal at Miami over the summer and now the growing problem in Penn State. Nevin Shapiro, a Miami booster, allegedly showered past and current Miami football players with gifts, parties, and money while at the school.

The NCAA hasn't concluded its investigation with The U, but most expect the penalties to be severe. Matula hopes that neither program -- despite the horrible allegations -- receives the death penalty, though.

You want the NCAA to be able to do something with this, but if you look at how corrupt they are, you don't want them to have any more power than they do, he said about Penn State. No football program deserves the death penalty, but I would love it if they could reduce their scholarships for 10 years.

The NCAA could ultimately decide to avoid punishing Penn State altogether or at least wait to see how the case plays out in criminal courts. Some have suggested that the NCAA sent a letter to the school simply as a way to avoid the stigma of doing nothing with such a big scandal, but that the organization will likely do nothing.

Swank, who was named one of the 50 most influential people in college athletics in 1994, thinks it'd send a very bad precedent for the NCAA to issue violations to the Nittany Lions.

The NCAA should and will stay out of this, he said. It's related within athletics but it involves criminal laws and not NCAA rules.

Emmert practically admitted as much in his letter to Penn State, but that doesn't mean it won't look for a possible loophole. Or if it can't warrant issuing the school violations this time around, it could create new bylaws to give it power to weigh in on issues of this nature.

The NCAA having power to deal with a case like this brings up mixed emotions for Matula. On one hand the disgusting and despicable nature of the crimes and subsequent lack of response leads him to want the NCAA to have power to deal with it, but the SMU fan in him lacks the trust in it.

The NCAA already has far too much power and to give them more, is folly, he stated. But however in a situation like this you just wish you could find a way for the NCAA to do something.

If the NCAA could have some sort of jurisdiction where if egregious laws are being broken and just basic humanity is being violated in a facility they are involved with, they should have some sort of say in it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.