Dogs Can See In Color! Scientists Determine Canines Can Use Color To Distinguish Between Different Objects

A widely accepted myth about our canine companions has been put in the doghouse by a team of Russian scientists.

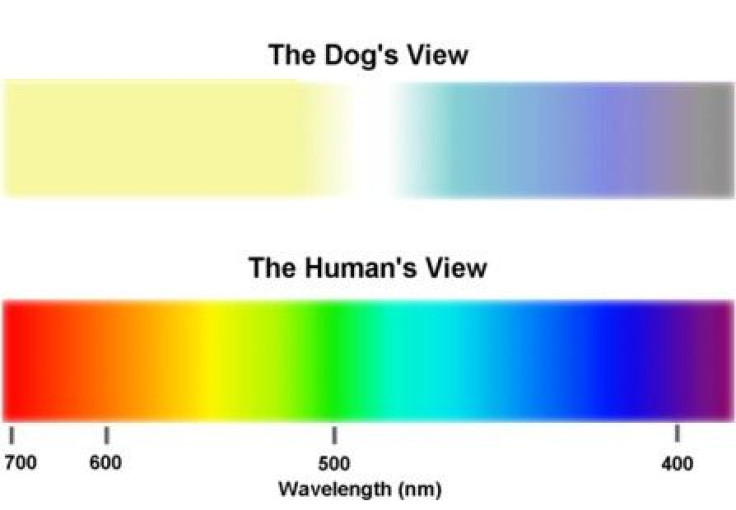

A common misconception about dogs is that they are able to see only in monochrome. But Russian scientists have now proven that dogs can in fact view a limited range of colors, reports the Daily Mail, using the shades to distinguish between different objects as well to pick specific items out of a lineup.

The team of researchers from the Laboratory of Sensory Processing at the Russian Academy of Sciences first tested the vision of eight dogs of differing sizes and breeds.

The test was then expanded last year to the University of Washington in Seattle, where scientist Jay Neitz coordinated tests that determined if dogs are able to see in color or not. Neitz is a professor of ophthalmology as well as a color vision researcher who has completed several informative studies on how color vision works.

Neitz found that compared to the three "cones" present in the human eye -- they allow the identification of red, blue, green and yellow light -- dogs only have two. Thus, dogs can detect blue and yellow light but are unable to see red and green.

From this research, the Russian scientists then printed four sheets of paper in dark yellow, dark blue, light yellow and light blue. The differing dark and light shades were used to test the idea that dogs rely on brightness levels to distinguish between two different items.

The first test used a dark yellow and light blue sheet of paper as well as a dark blue and light yellow pairing of papers. These were put in front of dog food bowls that were located inside of locked boxes.

The scientists then unlocked one of the boxes and placed the dark yellow paper in front of the box which contained a raw piece of meat in every trial.

In each test, the dogs were allowed to attempt to open the boxes before they were carried away.

After just three trials the dogs were able to learn which shade of paper was placed in front of the box with the raw meat. When the scientist determined the dogs were able to associate the dark yellow paper with meat being near by, they then wanted to test if the dogs were choosing the paper because of its brightness or its specific color.

In order to determine this, they placed dark blue paper in from of of one box and light yellow paper in front of the other. Scientists concluded that if the dogs chose the dark blue paper, they would be able to rule out that the animals were making choices led by the paper's brightness.

If the light paper was chosen, then they were choosing the boxes based on color.

Each dog chose the light yellow paper more than 70 percent of the time, evidence that the dogs were choosing based on color. And six out of the eight dogs mad the color choice between 90 percent and 100 percent of the time.

This allowed the researchers to conclude that color cues offered dogs more information regarding their item choices than the brightness of the paper.

"We show that for eight previously untrained dogs color proved to be more informative than brightness when choosing between visual stimuli differing both in brightness and chromaticity," said the scientists in a statement accompanying the study.

They stressed that "brightness could have been used by the dogs in our experiments," but the animals did not use that information.

"Our results demonstrate that under natural photopic lighting conditions color information may be predominant even for animals that possess only two spectral types of cone photoreceptors."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.