Don’t Like NBA Jersey Sponsorships? Five Reasons They’re Here To Stay

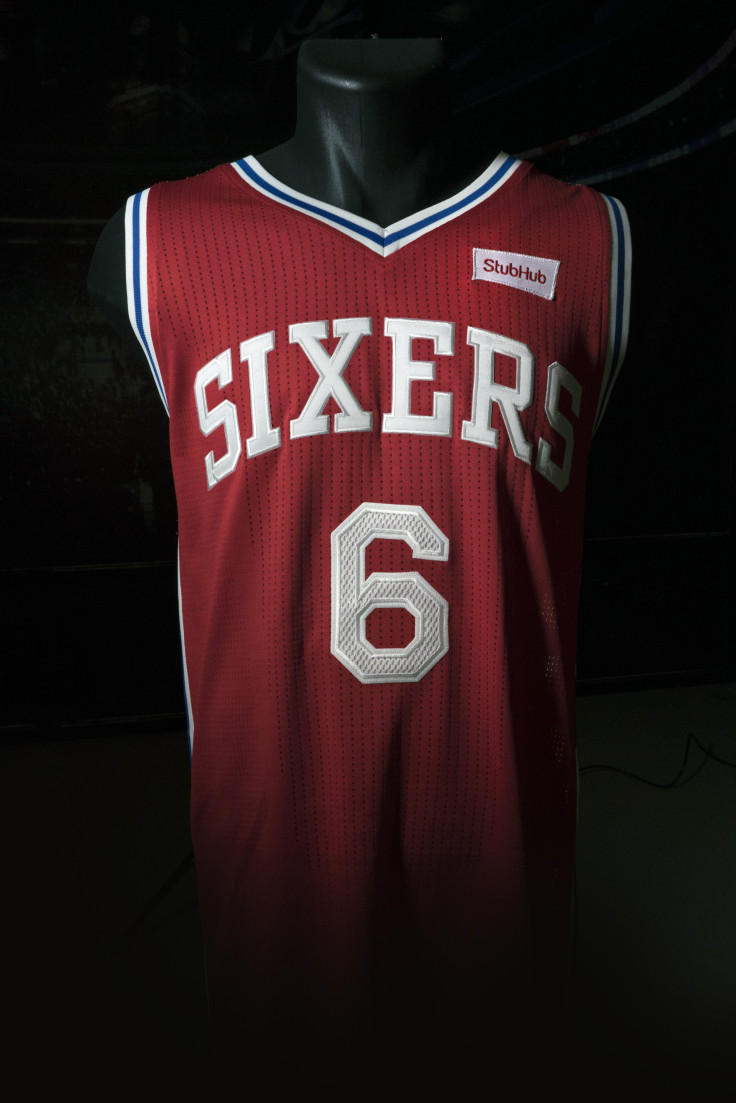

The Philadelphia 76ers on Monday became the first team in a major U.S. sports league to announce they would put a corporate logo on their jerseys. It's probably a safe bet they won't be the last.

The NBA approved the 2.5-inch-square patch advertisements, scheduled to debut in the 2017-18 season, about a month ago. The Sixers, the league's worst team this year, are leading the way in what could be a long procession of NBA franchises aligning with corporate sponsors for jersey ads. And be assured the other major U.S. sports leagues — the NFL, NHL and MLB — will be watching to see how the move works out.

"The Big Four have had a really good run. … We're at that point where we're always looking for new opportunities," 76ers CEO Scott O'Neil told International Business Times.

Here are five reasons why the opportunity the Sixers have pioneered could be here to stay:

There's money in it. A lot of money. Sports team owners, like the rest of us, enjoy making money. StubHub and the Sixers didn't disclose the terms of the deal, but an ESPN report pegged it at three years and $5 million per year. That's just the proverbial drop in an industrial-sized bucket. NBA Commissioner Adam Silver said in April that the league estimated the small patches would be worth at least $100 million annually.

You can't talk jersey sponsorship without bringing up soccer, where the practice is ubiquitous. The English Premier League led the way last year by raking in about $373 million from front-of-jersey sponsorship, according to Repucom's 2015-16 European Football Jersey report. The U.S.'s Major League Soccer, which the NBA dwarfs, pulls in more than $6 million annually by selling jersey sponsorships.

The money from jersey ads is planned to be a rising tide for all NBA boats, since each team's deal would be split 50-50, half going to the franchise, half to the league's revenue-sharing pool.

There could be even more money in it. As it stands, the StubHub-branded Sixers jerseys will be sold at the team's home games, but fans making purchases nationwide won't have to buy a shirt sporting the logo. If that changes as fans grow more comfortable with the concept, the value for deals could be even higher. Imagine a team switches sponsors: Then a fan with the old sponsor's logo looks out of date and might be compelled to buy a new jersey. That equals more jersey sales for franchises. And for the sponsor, of course, the team's fans become walking billboards.

Fans don't seem to mind (too much). If you comb through Twitter, you'll find plenty of fans upset about jersey ads. The traditionalist argument against jersey ads comes down to ruining the integrity of a team's history. Baseball, the national pastime, is perhaps the American sport most attached to history and tradition. MLB's oldest team, the Atlanta Braves, dates back to 1871.

But tradition is also big for English soccer clubs, which are neighborhood institutions closely tied to their hometowns. The Premier League's Stoke City dates back to 1863, and most clubs go back to at least the early 1900s. Yet English soccer fans have embraced jersey ads. People who love the game still love the game.

"Realistically speaking, NBA fans have been buying jerseys with advertisements since the beginning of NBA jersey retail. A team’s jersey, whether it says 'Knicks,' 'Lakers,' or 'Celtics' in its custom font, is inherently a wearable advertisement for the team," Justin Block, of the Huffington Post, points out.

The Sixers' ownership group is also involved with English soccer club Crystal Palace. "I can't imagine going to that game and seeing people wear the kits without the logo. You almost can't imagine it," O'Neil said.

Silver pointed out last year that fans have already watched NBA events with small jersey ads and didn't seem to care.

"During the slam-dunk competition on Saturday night of All-Star Weekend, all the contestants were wearing a Sprite logo on their jersey. It was fascinating to me it got almost no attention," he told the Portland (Oregon) Tribune.

It's a growing market. As technology has changed how we watch TV, live programs like sports games have become more and more valuable, and the value of jersey ads has grown likewise. In 2010-11, shirt sponsorships in the Premier League were worth about $170 million. They've grown 119 percent over the five years since. The Premier League's shirt sponsorship haul grew 35 percent over the last year alone.

Brands see value in tying themselves to uber-popular sports teams. StubHub was especially keen to be the first brand to make the move in the U.S. They'll have an exclusive partnership with the Sixers.

"That amazing play, that life experience, that play that’s captured on film, we’ll be there … we'll be on the player's chest," StubHub President Scott Cutler told International Business Times.

Other leagues are testing the waters. The NFL is an absolute giant atop the U.S. sporting world, and ads on jerseys remain one of the few revenue sources football has left untapped. The league already has ads on practice jerseys. If the cellar-dwelling Sixers can get $5 million per year, imagine, say, what the Dallas Cowboys could pull in.

Imagine an NFL exec this morning: The Sixers got how much? The SIXERS?? Says here ads on NFL jerseys in 3 years.

— Matt Powell (@NPDMattPowell) May 16, 2016

And the owners will say we're leaving how much on the table? https://t.co/udhEOixWcD

— Matt Powell (@NPDMattPowell) May 16, 2016

MLB spokesman Matt Bourne told Sporting News in April that baseball was "not considering putting corporate logos on MLB uniforms for games at this time." But the league has already put logos on helmets for exhibitions outside the U.S. and, as Vice pointed out, has been open to such marketing ploys as referring to grand slams as "Papa Slams" to benefit its official pizza sponsor.

With yesterday’s #PapaSlam, you can enjoy 40% off regular-menu-priced pizza. Code: PAPASLAM https://t.co/VFtCMUnCTz pic.twitter.com/tdqV1ZEKS0

— MLB (@MLB) April 15, 2016

NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman has expressed reservations about allowing logos but admitted that money talks. And hockey, like the NFL, already has ads on practice jerseys. "Our sweaters [jerseys], among all the other sports, are I think iconic, which is why I’ve previously been quoted as saying, ‘We certainly won’t be the first’ and you’d probably have to drag me kicking and screaming [to do it], which would take a lot – a lot, a lot – of money," Bettman told the Globe and Mail.

If the first U.S. deal is any indication, and if the Premier League serves as an example, Bettman might just get dragged along.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.