Don't Panic! Mexico Shows G-20 Leaders How Greece Can Recover

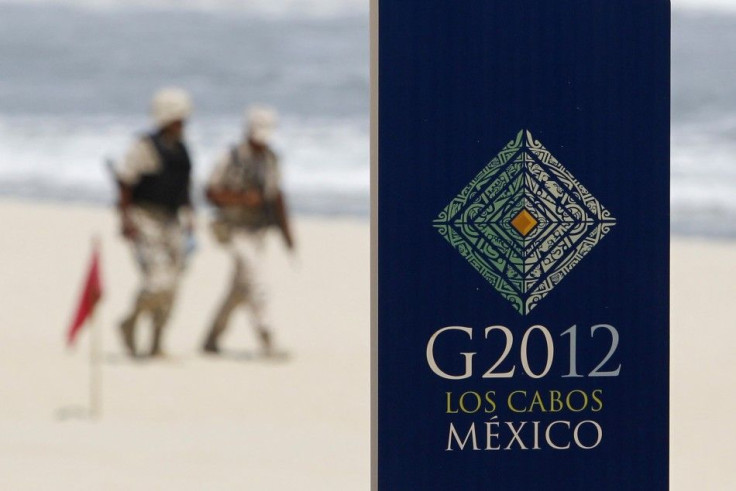

As world leaders gather in Mexico for the start of the G-20 summit Monday, Europe's debt crisis will be uppermost in their minds.

With Sunday's Greek election result averting instant panic but doing little to ease long-term fears that the country still faces a messy exit from the euro, the G-20 delegates are left to speculate on how to tackle a spiraling crisis with no clear end in sight.

The signs that this year's G-20 meeting in Los Cabos will emerge with a bankable solution are not strong.

Statements from world leaders have already poured cold water on any notion of a comprehensive plan to the European crisis emerging by Wednesday.

For that, analysts will have to wait until June 28 and 29, when the continent's leaders meet at a European Union summit intended to formalize some sort of plan to dig the euro zone out of its current hole.

But while the delegates may feel deflated and lacking in answers before events unfolding an ocean away, they would do well to remember the recent past of their hosts.

During the mid-1990s, Mexico's economy contracted massively, plunging the country into an economic hole not too dissimilar to Greece's scenario today.

In December 1994 the peso currency collapsed, causing the economy to shrink by 7 percent the following year.

Key industries suffered terribly; manufacturing shrunk by 6 percent, construction by 22 percent and agriculture by 4 percent.

But by 1996, the decline had been halted. That year the economy contracted by only 1 percent during the first quarter and returned to growth of around 7 percent by the second.

In another nod toward the current European crisis, Mexico also was aided by a $50 billion loan from the Clinton administration, the IMF, the Bank of International Settlements and the Bank of Canada.

Along with other Latin American nations that suffered during the 1980s and 1990s, Mexico managed to dig itself out and emerge as one of the Western Hemisphere's strongest economic contenders.

A lot of countries are belly up, and we are not. We have ideas about how to face these things, David Mena Alemán, a professor of international affairs at the Iberoamericana University in Mexico City, told The Christian Science Monitor.

There are things that would have detracted from any prestige or recognition of the Mexican government -- why there are so many poor and all the drug trafficking -- but there is a megacrisis out there, and [countries] are willing to listen to how we dealt with it and how we are dealing with it.

Putting aside the shocking drug violence, Mexico has indeed become one of the region's rising economic stars.

If Mexico were a stock, now might be the time to buy, David Shirk of the University of San Diego's Trans-Border Institute told the BBC.

The country has been severely undervalued in recent years.

According to Shirk, Mexico is enjoying increased economic importance as the world's seventh-largest oil producer and the third-biggest foreign oil supplier to the U.S. market.

And it is not only oil where the Latin American comeback kid is making waves.

Alongside the growing middle class, Mexican investors either own or have stakes in major U.S. businesses, including Dairy Fresh Milk products and The New York Times.

Mexico was arguably the 'Greece' of the 1980s and 1990s, suffering excruciating debt and monetary crises, Shirk added.

But Mexico ... is Greece no more.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.