Double-Drug Diabetes Treatment Disappoints In Kids [STUDY]

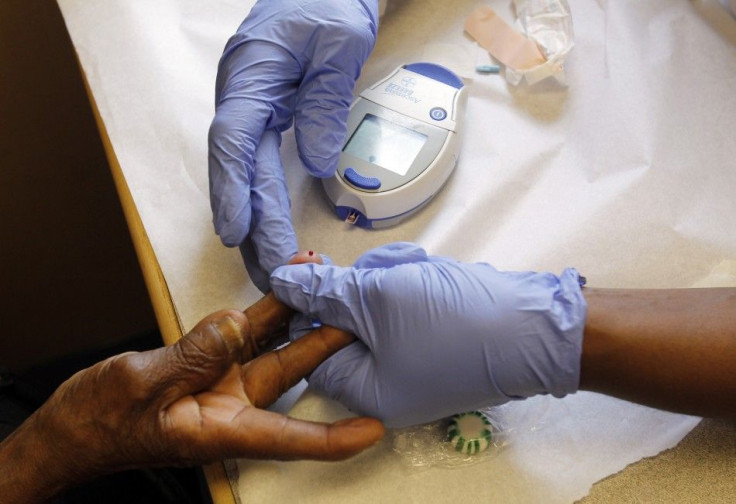

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - In a large new trial looking at ways to slow the progression of type 2 diabetes in children and teens, the addition of a second drug to the mainstay treatment metformin was only marginally more effective at controlling blood sugar than metformin alone.

Within a year, on average, half of kids on metformin and some 40 percent taking both metformin and rosiglitazone (Avandia) ended up having to resort to insulin injections to control their blood sugar, researchers reported Sunday at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Boston and in the New England Journal of Medicine online.

The results of the study were discouraging, said Dr. David Allen from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in an NEJM editorial. These data imply that most youth with type 2 diabetes will require multiple oral agents or insulin therapy within a very few years after diagnosis.

All 699 children included in the study had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes two years or less before enrollment, so the rapid advance of about half to needing insulin marks an early start to a potential lifetime of complications and side effects -- from the diabetes itself and the medications used to treat the disease.

Type 2 diabetes, the form usually associated with obesity, was once considered an adult disease, but is showing up in more and more teenagers, paralleling a rise in childhood obesity. And the condition is harder to treat in kids, experts say.

Type 2 diabetes progresses more rapidly in youth, according to Dr. Phil Zeitler from the University of Colorado, Denver, who worked on the new study.

He and his colleagues were surprised at how quickly many of the youngsters needed to switch from oral medications to taking daily insulin shots, Zeitler told Reuters Health.

Also, Zeitler said, the teens in the study appeared to have complications, including infections and hospitalization, more often than adults do.

All the children in the study were overweight or obese, and ranged in age from 10 to 17 years old.

Youngsters with diabetes are a difficult population to work with, Zeitler noted. Many of them don't take their medications as instructed. And in the first place, to get type 2 diabetes before adulthood, the toxicity of your lifestyle must be pretty severe, Zeitler said.

That's why all of the kids in the study got at least basic lifestyle counseling, he emphasized -- for example, advice to stop drinking sugared sodas, eat less fast food, watch their diet in other healthy ways, take stairs instead of elevators and generally get more exercise.

Study enrollment began in July 2004 and follow-up continued through February 2011. All the kids in the study were taking metformin, a well-established diabetes drug, and a third were assigned to take the newer drug Avandia as well.

Another third of the kids were assigned a very intensive lifestyle intervention, that involved more assignments for kids to complete, more interaction with counselors, and close involvement of at least one parent, in addition to taking metformin.

The kids' treatments were deemed failures if blood sugar and other signs pointed to their diabetes not being under control for a period of six months or more.

In the end, 52 percent of kids on metformin alone failed treatment, along with 39 percent of kids on metformin and Avandia and 47 percent of kids on metformin and lifestyle changes.

The median time it took for blood sugar control to be lost was just under a year.

The added benefit of Avandia was limited to girls, for reasons that are unclear, the researchers reported.

Also for unknown reasons, they noted, metformin alone was less effective for non-Hispanic black participants than other kids.

Surprisingly, kids on the combination of metformin and Avandia gained the most weight during the study, despite their slightly better rate of diabetes control. Kids in the lifestyle intervention group gained the least weight.

Zeitler pointed out, You can see in the data a suggestion that there might be groups of children who respond to the very intensive intervention. Our challenge now is: Can we identify the kids who are going to respond to a lifestyle intervention and (just one oral diabetes medicine)?

Conversely, he continued, the challenge is also to recognize from the start the kids for whom the intensive lifestyle intervention is going to be ineffective and not worth the time and money.

Overall, 19 percent of the participants developed serious adverse effects such as severe hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis and lactic acidosis.

The rate in the treatment groups was 18 percent in the metformin-only group, 15 percent in the double-drug group and 25 percent in the group that received the very intensive lifestyle intervention, but the rate of specific problems, such as hyperglycemia, were not significantly higher between the groups.

Finding the reasons for the differences between these groups of children in their response to treatments will require further research, Zeitler and his colleagues conclude in their report.

In his editorial, Allen says it's critical to remember that the patients in this study are youth immersed from a young age in a sedentary, calorie-laden environment that may well have induced and now aggravates their type 2 diabetes.

Fifty years ago, the editorial continues, children did not avoid obesity by making healthy choices; they simply lived in an environment that provided fewer calories and included more physical activity for all. Until a healthier 'eat less, move more' environment is created for today's children, lifestyle interventions like that in the ...study will fail.

SOURCE: bit.ly/InSsRZ New England Journal of Medicine, online April 29, 2012.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.