Earth's Two Moons Collided Creating an Asymmetrical One: Theory

Earth once might have had two moons, according to researchers.

The theory postulates that in a slow motion collision -- which lasted up to several hours, -- the smaller of the two moons slammed into our moon, leaving only one moon to orbit the Earth, and a mountainous formation on the far side of it.

"Traces of this 'other' moon linger in a mysterious dichotomy between the Moon's visible side and its remote far side," says Erik Asphaug, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who co-authored the study with Martin Jutzi, now of the University of Berne in Switzerland.

"By definition, a big collision occurs only on one side," Asphaug says, "and unless it globally melts the planet, it creates an asymmetry."

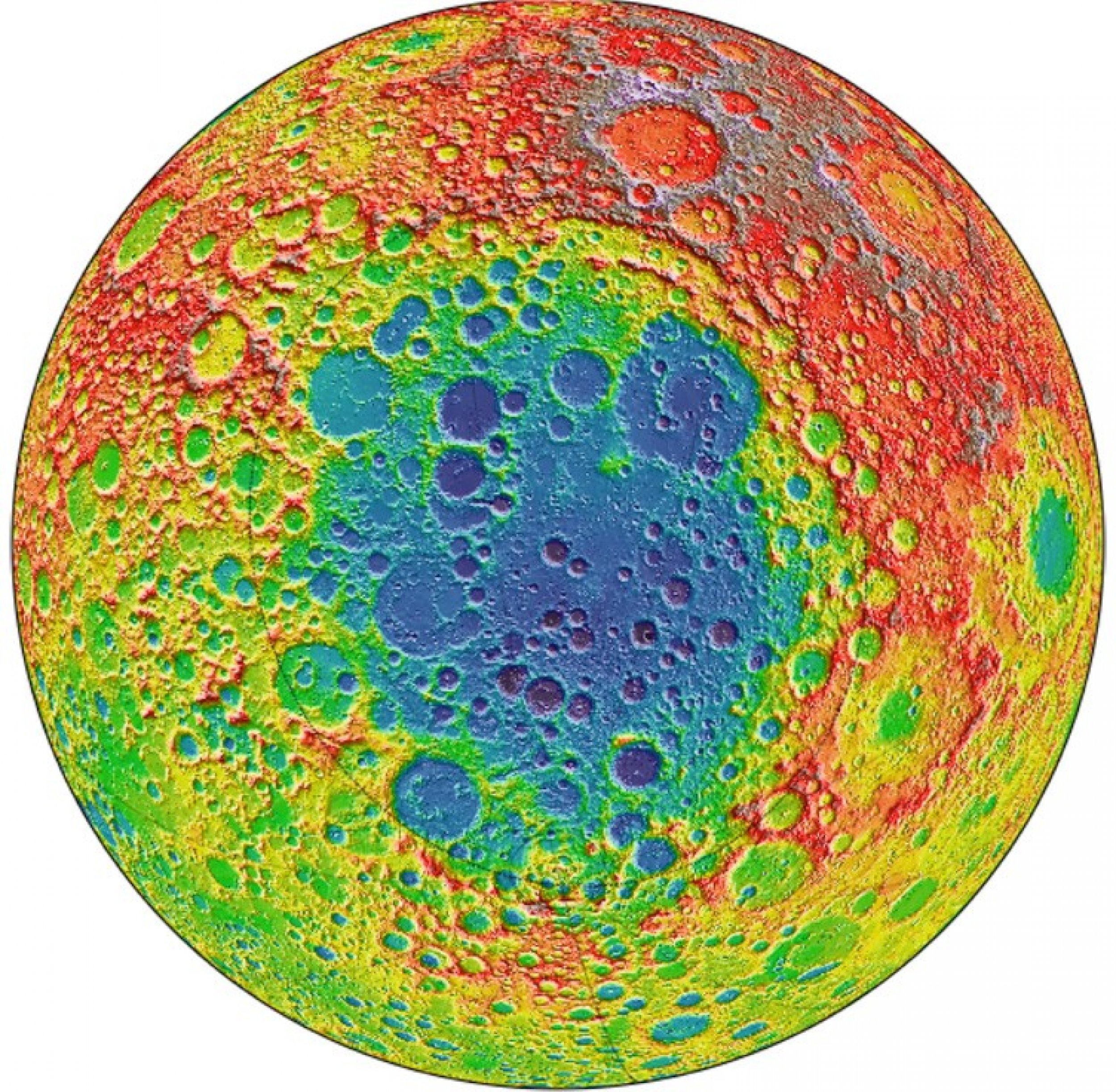

The side of the Moon which faces Earth is relatively flat, while the rarely-seen opposite side of the Moon is full of craters and has mountainous ranges. Scientists have been trying to figure out what could have caused the asymmetrical shape. Various theories have been proposed, but no final conclusion has been made.

Asphaug said he was in a discussion about this asymmetry when he got the idea. "I thought, 'Well, you know, what about just something colliding with the moon, in such a manner that it didn't form a crater, but it just made a big splat?'" he thought.

Rather than creating a crater in the moon, the collision created a large amount of debris, which stuck to the moon, forming piles of debris, and later, mountains. "And what you're seeing when you look at the lunar far side, if our theory is right, is you're actually seeing the planet that collided with it," says Asphaug.

Maria Zuber, a planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge says "all these collisions tend to make holes as opposed to mountains. It took, in the simulations, a fairly specialized set of conditions to make a mountain rather than a crater."

"I think this idea is going to get a lot of attention because it's very novel, it's very clever, and people are going to be interested in testing to see whether it's right or wrong," says Zuber.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.