EKGs Can Help Predict Heart Disease Risk In the Elderly: New Study

Monitoring the electrical activity in the heart could be a good new way to pinpoint heart attack risk in elderly patients and help doctors steer their patients away from coronary heart disease, researchers said in a new study on Tuesday.

In middle-aged people, doctors usually determine heart disease risk is based on factors like a history of smoking or high blood cholesterol levels.

But looking at these factors is not as helpful in gauging the risk for older people that haven't had heart problems before, according to University of California San Francisco researcher Reto Auer, the lead author of a paper appearing in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

And with a rapidly aging population, there's a growing effort to try and find new methods to predict heart attack risk in the elderly, Auer said in a phone interview.

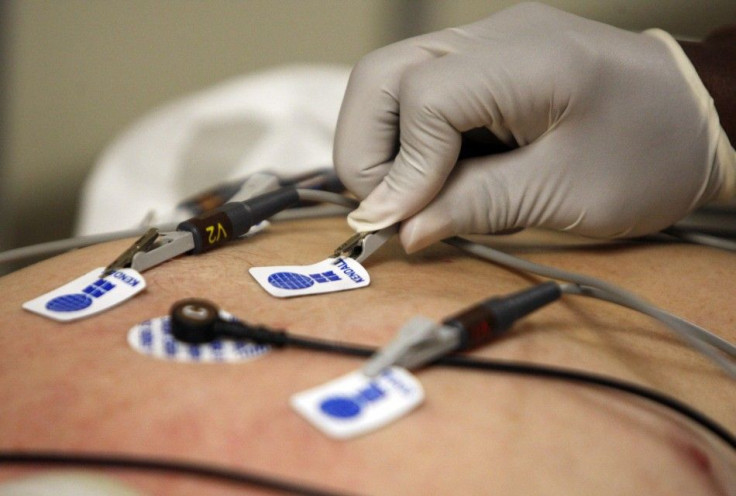

Enter the electrocardiogram, commonly known as an EKG or ECG. This test records the electrical impulses traveling through the heart using electrodes and translates that activity into a graph of spikes and valleys.

Sometimes abnormalities crop up on an EKG reading, making the readout look different. One common abnormality is called a bundle branch block, where the graph shows a wider trough than normal. This kind of abnormality happens when one of the wires conducting electrical current in the heart does not work anymore, according to Auer.

People can live a normal life with this abnormality and are most of the time unaware of the abnormality, Auer says.

However, these kinds of abnormal readings could be a warning sign . While studying more than 2,000 patients in their 70s, Auer and his colleagues found that abnormalities like the bundle branch block and others are associated with coronary heart disease events.

More than a third of the patients studied had some minor or major EKG abnormality at the start of the study. After eight years, 351 of the patients suffered some coronary heart disease event - 96 deaths from heart disease, 101 heart attacks, and 154 hospitalizations for chest pain or cardiac bypass surgery.

After analyzing the data, the researchers found that the risk for a heart disease event increased by 35 percent for patients with minor EKG abnormalities, and increased by 51 percent in patients with major EKG abnormalities.

The findings were similar for black and white patients alike.

In a JAMA editorial accompanying the study, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine dean Philip Greenland notes that several medical groups, such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, advise against ordering routine EKGs for patients with no symptoms of heart disease.

However, due to the implications of the current study, a cost-effectiveness analysis would be a logical next step in determining whether or not routine EKGs could become a recommended test, Greenland says.

The researchers, for their part, aren't urging people to rush out and get an EKG done; whether or not the procedure should be incorporated in routine screening of older adults should be evaluated in randomized controlled trials, they wrote.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.