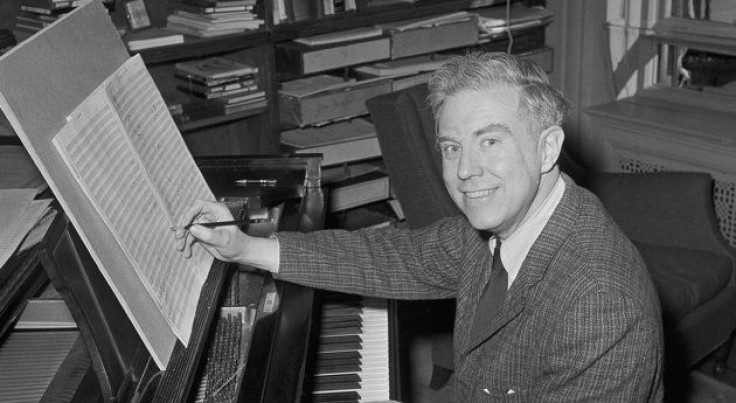

Elliott Carter, Pulitzer Prize-Winning Composer, Dies At 103

Elliott Carter, the critically acclaimed and two-time Pulitzer Prize winning American composer, died in his Manhattan home on Monday. He was 103.

A prolific composer, Carter composed 158 pieces during his 75-year-long career, continuing to write new music even after he reached the age of 100, and stopping only shortly before his death. He completed his last work, “12 Short Epigrams for piano,” in August.

Carter’s death was announced by the music publisher Boosey & Hawkes although they did not immediately provide a cause of death. In a statement, the company said, "The great range and diversity of his music has, and will continue to have, influence on countless composers and performers worldwide. He will be missed by us all but remembered for his brilliance, his wit and his great canon of work."

Over the course of Carter’s long life, his music has invariably been described as both structurally challenging to understand and perform, and difficult to listen to. Perhaps known best for his experimentation with rhythm, Carter described his body of work in a 1992 interview with the Associated Press as, "music that asks to be listened to in a concentrated way and listened to with a great deal of attention.”

“It's not music that makes an overt theatrical effect,” he said, “but it assumes the listener is listening to sounds and making some sense out of them."

When asked why he chose to write music that was so challenging – a 2002 New York Times article referred to Carter’s string quartets as being in the ranks of "the most difficult music ever conceived” – Carter maintained that he was taught only to write the music he cared most about.

“As a young man, I harbored the populist idea of writing for the public,” Carter once explained during an interview. “I learned that the public didn’t care. So I decided to write for myself. Since then, people have gotten interested.”

But that interest did not come quickly or easily for Carter. Many critics and even some of his early mentors found his work to be dissonant and grating. When one particular piece of Carter’s that he described as having “all kinds of rhythmic innovations in it” was played at a concert hall at Columbia University, he remembered that not all of the concert attendees were entirely receptive. “A number of people in the audience got up and rather loudly said, ‘This never would have been played if he hadn't been a teacher here,’” Carter recounted in a 2002 interview.

Although Carter shirked away from writing music that would please the public, he was venerated within a small circle of musicians and composers, and continued to receive commissions well into his final years. In speaking of the feedback he received from BMI over the years, Carter said he was often surprised by the frequency with which his pieces were performed.

“Almost every one of my various zero numbered birthdays has had a big concert in London and often in Paris. The Royal Festival Hall, I don't know whether it was 80 or 70, gave a whole festival of my music there with orchestra and everything. String quartets,” he said. “They weren't that well attended to tell you the truth, but they were attended and I'm always glad to have somebody listen to my music of course.”

In addition to the two Pulitzer Prizes that Carter received, in 1960 and 1973, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts by the United States in 1985.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.