European Financial Crisis Provides Scary Lesson For The World

OPINION

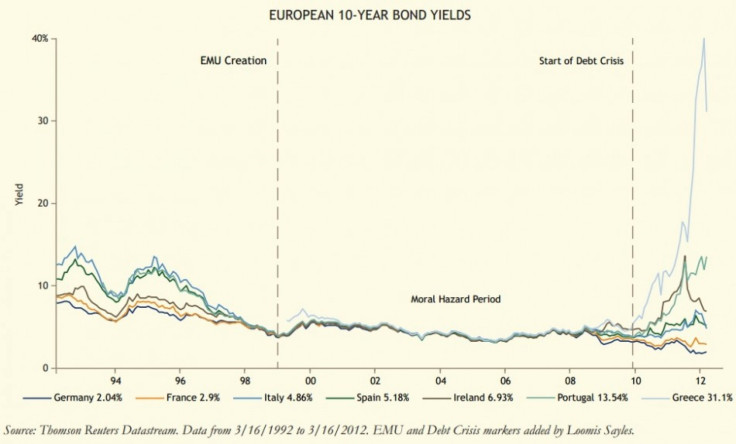

A recent paper by Thomas Fahey, associate director of macro strategies at Boston-based investment firm Loomis Sayles, showed how quickly the tranquility of the euro zone turned into chaos.

This revelation from the European crisis has grave implications for assessing the threat of the next global financial meltdown.

As seen in Fahey’s chart below, the euro currency worked remarkably well for the first eight years of its existence.

During this period, yields on 10-year government bonds of weaker euro zone members Greece and Portugal converged to the low yields of Germany, Europe’s most creditworthy country. Single-currency proponents at the time began to dismiss skeptics, citing the bond market as evidence of the euro's success.

This perception, however, was shattered in a matter of 10 months, starting in October 2009, when Greece’s 10-year yields soared from 4.5 percent to 10.3 percent.

Three weeks ago, the Greek credit event smashed the seeming truism that advanced economies don’t default in the modern era.

Across the Atlantic, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and other U.S. policymakers may be in the same boat as their European counterparts a decade ago.

Bernanke insists there is no threat of inflation, despite his decision to keep interest rates near zero since late 2008 and triple the size of the Fed's balance sheet to nearly $3 trillion.

The proof he cites is the current low level of inflation and “financial market indicators.”

For example, yields on long-term U.S. Treasurys, a measure of inflation expectations, are at historic lows.

Data from Federal Reserve, chart made using Microsoft Excel

Yields on long-term government bonds are also a gauge of a country’s creditworthiness, leading some to dismiss fears about the United States’ exploding government debt, which has risen above 100 percent of gross domestic product.

Back in April 2011, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner famously said on Fox Business Network that there was “no risk” the United States would lose its AAA credit rating.

Just four months later, Standard & Poor’s downgraded the U.S. rating to AA+ from AAA, although the bond market itself hasn’t yet revolted against long-term Treasurys.

Bernanke, too, has little credibility when it comes to financial and economic predictions.

In February 2004, he said the U.S. economy has entered the period of “Great Moderation,” which is characterized by reduced macroeconomic volatility. He had expected the tranquility to “persist.”

In March 2007, he claimed that the “impact on the broader economy and financial markets of the problems in the subprime market seems likely to be contained.”

Nevertheless, Bernanke and Geithner may ultimately be right in their calls of no uncontrolled inflation and no U.S. sovereign debt crisis.

U.S. banks are choosing to not lend, short-circuiting the inflationary effect of the Fed's loose monetary policy.

And despite ballooning debt, the U.S. dollar is the global reserve currency, which for now leaves investors little choice but to buy Treasurys.

Still, excesses, which are clearly building in U.S. public debt and the Fed's balance sheet, have a strong history of destroying long-held financial and economic truisms.

Moreover, it is disconcerting that Bernanke relies on “financial market indicators,” which arguably betrays his lack of understanding of financial crises.

In the years leading up to financial crises, financial markets and the economy will likely be unusually stable and prosperous, whether it’s falling Greek yields or steadily rising U.S. home prices.

This boom, however, shouldn’t be mistaken for safety. Instead, it is the building up of excesses, which are both masked and fueled by liquidity.

If uncontrolled inflation or a U.S. sovereign-debt crisis were ever to materialize, people like Bernanke will once again be fooled by “financial market indicators” and fail to see it coming.

Fahey, of Loomis Sayles, believes investors should be on the lookout for the next liquidity-fueled boom and bust.

Believing bank credit to be an essential ingredient of bubbles, he recommends “watching for any sign that booming credit” in emerging market countries with healthy banking systems.

Chart from Thomas Fahey of Loomis Sayles

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.