Evolution Of The Human Face Linked To Prehistoric Violence: Study

Ape-like ancestors of modern-day people engaged in violent fights over disagreements as well as over women and resources, which contributed to the evolution of the human face, according to a new study.

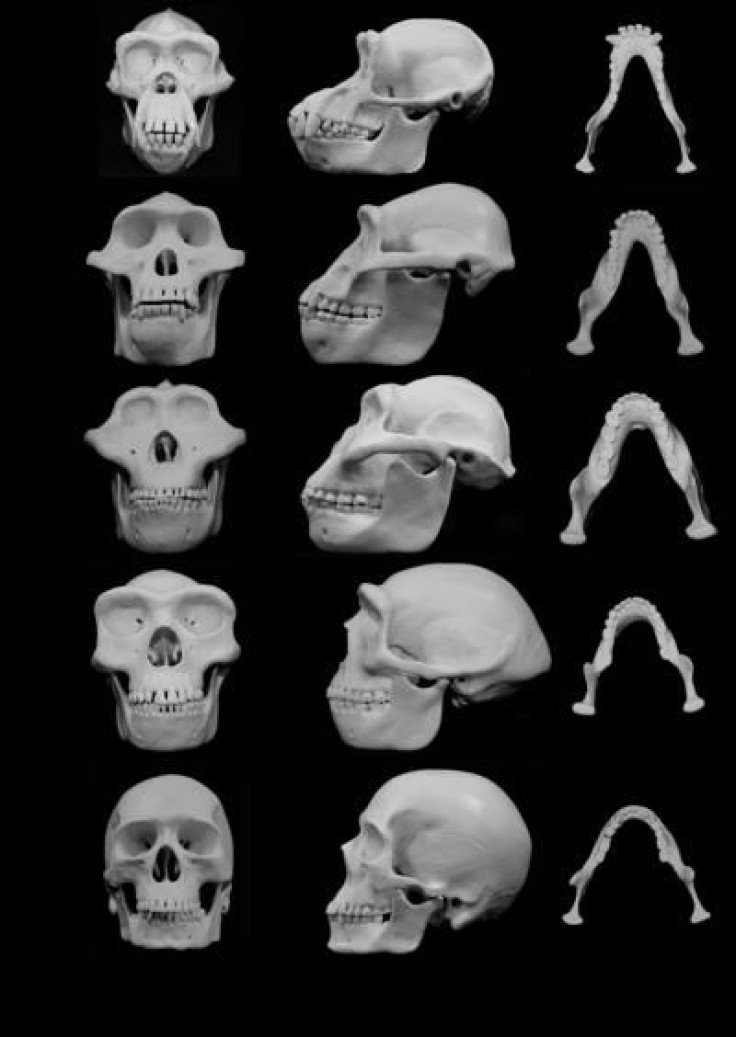

The findings of the study, published in the journal Biological Reviews on Monday, revealed that the human face, especially those of our australopith ancestors, developed to minimize injury caused by punches to the face during fights between males. Australopith, as described by Encyclopaedia Britannica, is a term “used to refer to members of the genus Australopithecus and other humanlike primates that lived in Africa between 6 and 1.2 million years ago.”

“The australopiths were characterized by a suite of traits that may have improved fighting ability, including hand proportions that allow formation of a fist; effectively turning the delicate musculoskeletal system of the hand into a club effective for striking,” David Carrier, a biologist at the University of Utah and the study’s lead author, said in a statement. “If indeed the evolution of our hand proportions were associated with selection for fighting behavior you might expect the primary target, the face, to have undergone evolution to better protect it from injury when punched.”

The researchers found that the bones that suffer the highest rate of injuries in hand-to-hand combat belong to a part of the skull that has grown to be strong during human evolution.

“These bones are also the parts of the skull that show the greatest difference between males and females in both australopiths and humans. In other words, male and female faces are different because the parts of the skull that break in fights are bigger in males,” Carrier said.

The new study, which contradicts a previously held hypothesis that the evolution of the human face is largely linked to a need for chewing hard-to-crush foods, is consistent with an earlier study indicating that violence contributed to human evolution to a great extent.

According to Carrier, the new study also throws light on the debate over whether early humans were violent.

“What our research has been showing is that many of the anatomical characters of great apes and our ancestors, the early hominins (such as bipedal posture, the proportions of our hands and the shape of our faces) do, in fact, improve fighting performance,” Carrier said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.