Facebook?s IPO Class Action Suits Echo Dot Com Era, But Investors Shouldn't Count Their Winnings Just Yet

Within a week of Facebook Inc.'s (Nasdaq: FB) $16 billion initial public offering, at least six lawsuits were filed against its top officials, including CEO Mark Zuckerberg, as well as six investment banks involved in the deal.

That in itself is not surprising. Facebook's May 18 debut as a public company was a flop, leaving many new shareholders angry as they watched shares plummet 9 percent on the first day; it's still trading down a third from its initial offer of $38.

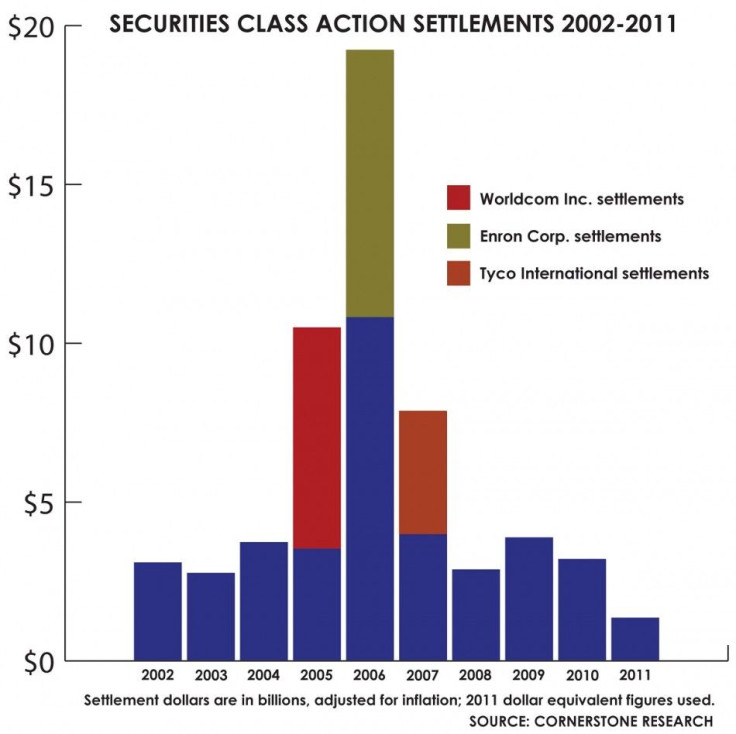

However, what would be surprising is if the shareholders actually get anything near what they feel they deserve. Total damages awards in shareholder suits have fallen to a 10-year low, according to Cornerstone Research, a financial and research firm that provides data to commercial litigation lawyers. In 2006, the peak year for settlements, investors received $19.1 billion; last year, that figure fell to only $1.4 billion, which was about 60 per below the year before.

This corner of the litigation market continues to run at a pace well below historic norms, said Joseph Grundfest, director of the Stanford Law clearinghouse, as well as a former member of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

New Sensitivities

A decade ago, U.S. courts handled a record number of securities class action lawsuits -- when shareholders sue companies -- mostly the reaction to the dot-com bust of the late 1990s and early 2000s. In many of these cases, deals between hyped-up tech start-ups and brokerage firms established sketchy quid-pro-quo arrangements leaving retail investors feeling jilted.

For example in 1998 a very early version of a social networking service, theGlobe.com, went public with an offer of $9 a share. The price peaked at $97 and settled at $63.50 by the end of the first day, marking the largest first-day gain for an IPO to that date. By 2001, the company was facing a slew of class action lawsuits by shareholders who claimed the company's IPO prospectus was misleading and that its underwriters, the now-defunct brokerage firm Bear Stearns, accepted commissions from elite investors who were allocated a portion of the limited number of shares prior to the IPO. TheGlobe.com still exists as a shell company and more than a decade after the lawsuits were filed a settlement in this case is still pending.

There's a higher sensitivity to these issues now, said Jeremiah Garvey, a securities lawyer with Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney in Pittsburgh. From the standpoint of these kinds of abuses, I think people are more comfortable that they don't occur,

These deals, as well as high-profile cases surrounding corrupt bookkeeping by Enron Corp., Worldcom Inc. and Tyco International Ltd. led to stricter standards that improved corporate governance but may have discouraged companies from going public. Whatever the case, class-action settlement costs now are at an historic low. The number of securities class-action complaints has been below-average in all but one of the past seven years.

There is now a lot of jurisprudence that makes the pleading standards much higher, much more difficult to prove, said Stanley Bernstein of New York-based Bernstein Leibhard, which filed a May 23 securities class-action complaint against Facebook. Securities laws themselves require particularized pleadings of fraud. You can't just say 'they committed fraud.'

Who Said What and When

In Facebook's case, the fraud allegation revolves around what information Facebook officials relayed to lead underwriters including JPMorgan Chase (NYSE: JPM) and Goldman Sachs (NYSE: GS), during the company's pre-IPO May roadshow. Specifically, the plaintiff's lawyers cite an amended prospectus filed by Facebook on May 9. In it, the company warned of possible losses due in part to increased use of mobile devices, something that PC-based Facebook has had problems monetizing because advertisers are wary about ads on small screens.

The lawsuits claim that amending the prospectus so close to the IPO led brokerage firms to downgrade Facebook's projected revenue performance, causing their major clients to stay away and the Menlo Park, Calif., company's share price to tumble on the first day, then close up only 31 cents. Generally, technology IPOs close much higher.

Plaintiffs say the reason that the stock price declined was because analysts at Morgan Stanley and at least three other underwriters lowered their earnings forecasts for Facebook's second quarter and the year, but only provided this information to their big-money clients. Internal analyst estimates about Facebook have not been made public.

After a week as a public company, Facebook's share price had plunged to $31.91 from $38, although this could have more to do with the bungled nature of the IPO. For the first 30 minutes of trading, Nasdaq was unable to execute orders.

If the plaintiffs' charges are true, that would bolster their case that Facebook filed misleading federally required disclosure statements by omitting what the experts were telling some clients. Questions would still remain regarding the role Facebook executives played, additional information they might have been given to the brokerage firms and if they knew about the lower earnings forecasts.

People refine their models all the time. The Morgan Stanley model, or downgrade if you will, or their view, is not part of the prospectus. It's just their view, said Garvey. The question really is going to be what led Morgan Stanley, if this is the case, to sharpen their pencils and refine their model-and where did that [decision] come from? They may have done it on their own.

The damages award asked for by investors is relatively straightforward, plaintiffs' attorney Bernstein said, because they only involve one day's worth of trading: if an investor bought shares at $38 and sold at $36, the damage is $2 per share. For an IPO that raised $16 billion, those increments could add up to a significant settlement cost to Facebook.

Plaintiffs have until mid-July to sue. Then a judge will pick one or more plaintiffs with the greatest losses to represent all shareholders in the class. It could take months before a settlement or judgment occurs. If no settlement is reached, defendants will file a motion to dismiss. If a judge denies that motion, the next step could be a settlement. Most securities class action cases are settled before a judge has to make a decision about trial.

Stricter Rules

One reason for a decline in the number of shareholder lawsuits and settlement costs is the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2000 which stemmed from abuses of the tech boom-and-bust as well as Enron's demise after a spate of illegal accounting activities were uncovered.

Sarbanes-Oxley set a higher bar for corporate governance. For example, it established the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, which oversees the work of company auditors and imposes stricter standards for financial disclosures. Under the law, the stock transactions of corporate officers and off-balance-sheet transactions of the company must be made public.

Sarbanes-Oxley also stipulated that senior executives must take personal responsibility for the accuracy of filings. That's one reason why Zuckerberg has been specifically named in the class action lawsuits and not just his company. All of the Facebook executives who signed the prospectus are defendants.

In addition, Sarbanes-Oxley requires brokerage firms to have a firewall between their analysts and client services. This part of the law brings in Facebook's underwriters as defendants, because the suits claim Morgan Stanley and other brokerage firms were relaying unpublished analysts' forecasts to their clients that were unavailable to everyone else, which is illegal.

Critics argue that reforms like Sarbanes-Oxley have played a role in the decline of IPO activity.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act . . . has been devastating for investors and promising startups, conservative columnists Jacqueline Otto and Ryan Radia wrote in an op-ed last year as media attention focused on a surge in high-tech IPOs. The law's onerous mandates on public companies have forced many nascent companies to forget about or delay going public.

However, the facts seem to run counter to this argument. In 2010, there were 153 US-based IPOs, up from a record low of 31, according to Greenwich, Conn.-based Renaissance Capital. Last year, 24 internet companies went public in the US, the highest in a decade; among them were successful and non-controversial debuts of LinkedIn Corp. (NYSE: LKND), the San Francisco-based professional networking service, Jive Software (Nasdaq: JIVE) and others whose prices have gained substantially.

Plaintiffs' burden

Post dot.com-era reforms haven't solely been focused on corporate behavior. Plaintiffs, too, have had new rules put on them that raise standards by which damages are determined.

In 2005 the U.S. Supreme Court settled an issue about how district courts decide whether a company's misrepresentation led to financial loss. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals required only that a plaintiff claim that the price of a stock on the date of purchase was artificially inflated due to misrepresentation for a suit to go forward. But the Supreme Court decided that a correlation between the misrepresentation and a plaintiff's financial loss must be established in order to prevent frivolous suits aimed at seeking pre-trial settlements.

This interpretation of causation has raised the bar considerably for how plaintiffs in securities class action cases determine damages. In the Facebook case this isn't an issue because the damages are linked directly to just the first day's trading -- so it doesn't involve inflating the price as much as the loss on that single day.

However in the class action recently filed against JPMorgan Chase -- in which shareholders claim the bank was aware of more than $2 billion in losses incurred on risky bets on European debt for weeks before disclosing it publicly -- the alleged illegality took place over a period of weeks. Consequently, the court will require plaintiffs to prove a direct causal link between stock price declines during nearly a month's worth of trading and the bank's alleged withholding of information and downplaying of media reports regarding its risky investments.

Still, however these most recent cases play out -- and odds are today they will end up favoring the companies and not investors -- a few things are certain: aggrieved investors will continue to sue companies they feel have been less than honest in their dealings; plaintiffs' attorneys will gladly take these cases (the figure varies, but attorneys generally get about a third of the settlement amount granted plaintiffs in a successful lawsuit); and the media will sensationalize the litigation as if the suits themselves and the damages alleged are already a finding of guilt.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.