Farthest Single Star Discovered By Hubble Space Telescope 9 Billion Light-Years Away

The natural phenomenon of gravitational lensing and the abilities of Hubble Space Telescope have come together fortuitously for astronomers, giving them a glimpse of the farthest known single star. Nicknamed Icarus, the massive and very bright ancient star is located 9 billion light-years away, though it would be more accurate perhaps to say it was located there, because it certainly doesn’t exist anymore.

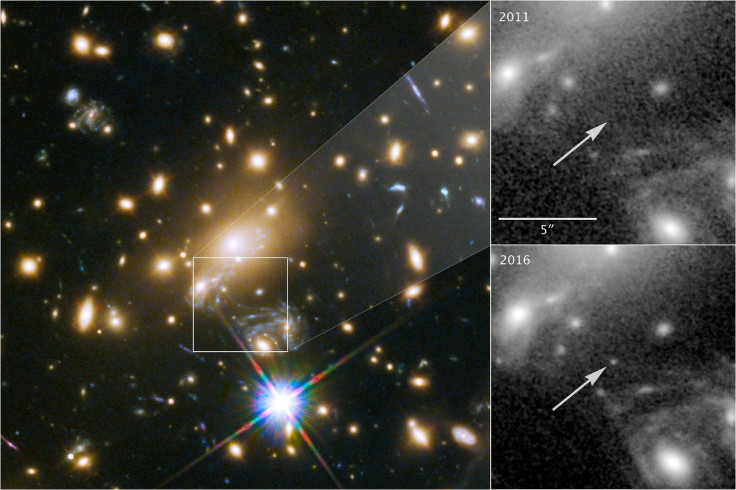

Icarus, formally called MACS J1149+2223 Lensed Star 1 (because it was a galaxy cluster called MACS J1149+2223 — about 5 billion light-years away — whose gravity bent and amplified the star’s light, allowing Hubble to spot it), was located in a spiral galaxy that existed when the universe was only a third of its present age. It was nicknamed after the mythical Greek character (who attempted to fly to the sun using wings glued on to his body with wax, which eventually melted due to the heat) for its perceived brightness. Its light was amplified about 2,000 times as it traversed the intervening distance.

“We were able to establish that Icarus is a blue supergiant star, a type of star that is much bigger, more massive, hotter and possibly thousands of times brighter than the sun. But, at its great distance, it would be impossible to observe it as an individual star, even with the Hubble, were it not for the gravitational lens phenomenon,” Ismael Pérez Fournon, a researcher at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC) and the University of La Laguna (ULL), both in Spain, explained in a statement.

Pablo G. Pérez González of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM), added: “Until 2016 is was only possible to observe individual stars in galaxies close to the Milky Way. Today, we are witnessing an individual star, very like Rigel, which is halfway across the Universe, and which, indeed, no longer exists.”

Rigel is a star in the Orion constellation, and usually the seventh-brightest object in the night sky. Its luminosity is several thousand times that of the sun, and its mass about 23 times. Currently about 10 million years old, it will likely die young too, probably as a supernova.

The distance at which Icarus has been observed is truly astonishing, comparable only to supernova explosions or galaxy clusters, and at least 100 times more distant than the next individual star we can spot using current technology.

Since gravitational lensing is dependent on the gravitational effect of a massive object in the foreground, acting on light coming from another object in the background, it is directly related to the mass of the foreground object. Since 85 percent of all mass in the universe is made up the mysterious dark matter, this observation also presented an unusual opportunity for scientists to test a dark matter theory.

By looking at fluctuations in the light from Icarus, as it moved through the galaxy cluster, the researchers concluded dark matter was unlikely to be made up of primordial black holes that spawned at the time the universe was born in the Big Bang. This was because the light fluctuations would have been different from Hubble’s 13-year long observations had it been moving through a swarm of black holes.

Hubble images from May show a second image, possibly another star — part of a binary system with Icarus.

A paper describing about the dark matter implications was published Thursday in the journal Nature Astronomy and is available on the pre-print server arXiv.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.