Fast Food Strike September 2014: 36 Arrested In NYC As Thousands Demonstrate In US For Higher Pay, Right To Unionize

Dijon Thornton is on the brink of homelessness every month. The 23-year-old from the Bronx isn’t unemployed, but the $800 a month he makes from his job at Wendy’s is barely enough to pay the rent and support his younger brother.

“I’m teetering,” Thornton said following a protest Thursday in New York City by fast-food workers and their advocates, where they demanded a minimum wage of $15 an hour and the right to unionize. “Paying the rent has come a little bit hard. I make sure that every cent is going to rent. It’s like you make your money a priority, and I don’t like worrying about money.”

The New York protest was one of 150 demonstrations held across the country Thursday and marked the latest struggle between corporations and workers amid a national debate over fair wages. Since fast-food workers first began protesting two years ago, Seattle raised its minimum wage to $15 an hour and Massachusetts residents will soon see an $11-an-hour minimum wage, according to NBC News. President Barack Obama earlier this year took executive action to institute a minimum wage increase from $7.25 an hour to $10.10 an hour for employees working under new federal contracts.

Thornton’s story is that of the typical fast-food worker today, according to Kendall Fells, organizing director of Fast Food Forward, the advocacy group spearheading the Fight for $15 and a Union campaign. The fast-food industry is among the fastest growing industries in the country yet is among the lowest paying, he said. Those who say fast food employees don’t deserve higher wages or that such a job is a stepping stone are behind the times, he said.

“That may have been true 10 years ago, but now these are careers. These aren’t the jobs of the ’80s, when kids worked to buy book bags and sneakers. These are jobs where moms are trying to feed their kids,” Fells said. “There’s no reason you should work for a $5.6 billion corporation like McDonald’s and then go to sleep in a park with your daughter.”

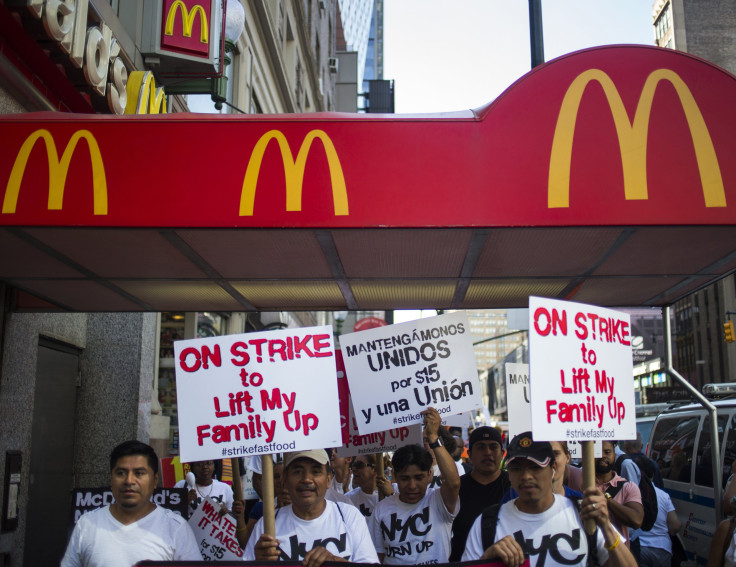

Dozens of protesters walked 10 blocks up 8th Avenue in Manhattan to a McDonald’s on 56th Street, banging on cowbells, beating on drums and chanting slogans such as “No Justice, No Peace,” and “Si Se Puede [Yes We Can.]” They held up signs reading “On Strike to Lift My Family Up,” “Whatever it Takes For $15 and a Union,” and “McDonald’s CEO Don Thompson made $13.8mn last year. WTF?” with the “W” formed by an upside-down McDonald’s golden arches.

Arlene Geiger, an adjunct economics professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said her status as a low-wage earner among academia makes her sympathize with fast food workers.

“I think it’s outrageous that people who work so hard and don’t get paid enough for rent and health care,” she said before the protest got underway. “It’s an affront.”

As they arrived by the corner of the McDonald’s, a handful of protesters sat in the middle of the intersection blocking traffic as police officers warned them over bullhorns to get up or they would be arrested on disorderly conduct charges. After they continued to sit on the ground, some were handcuffed in a sitting position while others stood up as they were being detained. Others were arrested at an earlier demonstration. In all, 36 demonstrators were arrested, according to police on the scene.

The $15 and a Union Twitter account posted photos Thursday of demonstrators being arrested in Boston and Hartford, Connecticut. Fast food workers also blocked intersections in Little Rock, Arkansas, and similar protests were held in Los Angeles, Houston, Denver, Kansas City, Milwaukee and beyond.

Among those arrested in New York was Jose Carillo, an 81-year-old who makes $8.10 an hour cleaning the lobby of the McDonald’s at 6th Avenue and 46th Street. Carillo said rent and sending money to his family back in Peru consumes his whole paycheck. It was his second time protesting his working conditions. McDonald’s suspended him the first time, he said, but a labor board got the company to reinstate him. Still, he said it was important for him to participate in the protest.

“I’m living miserably. I’m just surviving,” he said through an interpreter. “I’m not only fighting for $15 and a union, I’m also fighting for the future generation.”

While protesters were demonstrating, their voices weren’t being heard by nearby McDonald’s and Wendy’s patrons. Many customers said they were unaware of the strike or the movement to increase fast food workers’ wages. Justin Adour, a 30-year-old Brooklyn resident and chaplain at the Merchant Marine Academy on Long Island, said the protesters’ demands weren’t unreasonable.

“I think there’s validity to the argument of a living wage,” he said. “Fifteen dollars in New York -- that’s not some insane wage for someone that’s working full time. You’re not going to get a penthouse on the Upper East Side. For these kinds of corporations, it seems greedy [not to raise wages].”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.