Fed Rate Hike: Why Seven Years Of Near-Zero Interest Rates Failed To Boost Wages

In the seven years since the Federal Reserve took the extraordinary step of lowering interest rates virtually to zero, a host of economic indicators have flashed positive. Unemployment has roughly halved from its 2009 peak of 10 percent. Companies took advantage of ultra-low borrowing costs to issue record levels of corporate debt for three years running. The value of stocks in the Standard & Poor's 500 index approximately tripled.

Yet for ordinary working Americans, wages have barely budged. Underwhelming wage growth, together with tepid inflation, has confounded U.S. Federal Reserve economists’ well-worn expectations about how low rates could pump up the American economy.

As the Federal Open Markets Committee, the key rate-setting panel of the U.S. central bank, agonizes this week over whether to lift rates from historic lows, eventually slowing economic expansion, the quandary of disappointing wage growth epitomizes the contradictory pressures the Fed faces in the modern economy.

Though economists disagree as to why wages have faltered during the recovery, the question gets to the heart of the Fed’s dual mandate -- to keep a lid on inflation while maximizing employment -- and has cast doubt over the scope of the Fed’s primary monetary tool.

Job Creation, Wage Stagnation

The standard economic theory goes that as the labor force reaches full employment, wages and inflation both rise. With a dwindling supply of unemployed workers available, companies lift wages to retain employees. At the same time, workers feel more comfortable demanding raises. Surging wages pull inflation up as companies increase prices to make up for rising salaries.

But in the wake of the recovery, that theory hasn’t quite panned out.

“Almost every job indicator tells us that the labor market has gotten tighter in the last six years,” says Gary Burtless, a labor economist at the Brookings Institution. “That’s a long time to go without any pickup in wages.”

Even as employers added 13 million jobs to their payrolls, yearly wage growth has hovered around 2 percent, well below the 3.5 percent economists consider necessary to see the Fed’s goal of 2 percent inflation.

Though there is some disagreement about how tight the labor market truly is -- the labor force participation rate currently stands at a three-decade low, largely because many workers have given up -- some observers find it strange that wage growth has seen almost no uptick.

Burtless says that the historical weakness of present-day organized labor plays a crucial role. “There has been an erosion in the bargaining power of workers, whatever the state of the economy,” he explains, citing a drop in union density from nearly one-third of private-sector employees in 1960 to 7 percent today.

“You would think workers would be demanding and gaining better pay and benefits, but that has not been occurring,” Burtless says.

The Long Shadow Of The Recession

Some, like Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President James Bullard, have suggested that wage gains might be imminent. In January, Bullard characterized wage growth as a lagging indicator, dismissing its importance to monetary policy.

In public comments, Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen has also downplayed the importance of wage growth in consideration of raising rates. “In real terms, wages have been about flat, growing less than labor productivity,” she said in a speech last year, suggesting that the absence of gains might point to hidden slack in the labor market.

But Yellen said that other factors could likely be at play, particularly “pent-up wage deflation.” According to the theory, companies that refrained from cutting wages in the depths of the recession might have taken longer to beef up salaries once the economy had picked up.

Moreover, Yellen said, long-term structural changes in production and global trade could also play a part in permanently dampening wage gains. If weak earnings growth wasn’t evidence of a weak labor conditions, a rate hike would be that much more likely.

But several factors have complicated the decision. While a vast majority of investors predicted earlier in the year that rates would rise by September, futures data indicate that only a quarter of investors now see it as likely in the run-up to the Fed meetings Wednesday and Thursday.

Lackluster inflation isn’t the only factor weighing on the Fed’s decision. Market turmoil in August and shaky economic conditions in China and other emerging markets have made this month seem an especially perilous time to change interest rates, even by the modest 0.25 percent the Fed is expected to eventually pursue.

The Only Game In Town

Labor conditions and recessionary effects don’t explain everything, argues Josh Bivens, research and policy director of the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute. To fully explain why wages haven’t gotten the same jolt from the Fed’s rock-bottom interest rates as other parts of the economy, he points a finger at another branch of the government: Congress.

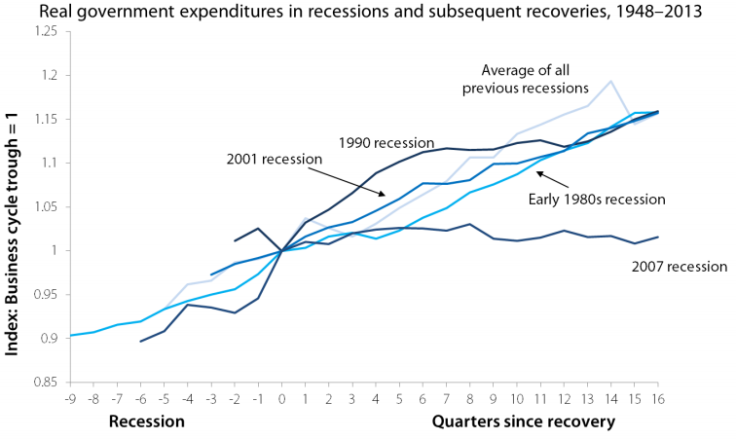

Bivens argues that fiscal policy following the recession failed to stimulate sufficient demand. “After the recession, fiscal policy has been historically austere,” he says. Despite two rounds of stimulus passed in 2008 and 2009, Bivens says the government still did too little in the way of programs like infrastructure building and providing unemployment benefits.

Bivens isn't alone in that notion. Yellen called fiscal policy an economic "headwind" in a 2013 speech. "In the year following the end of the recession, discretionary fiscal policy at the federal, state, and local levels boosted growth at roughly the same pace as in past recoveries," she explained. "But instead of contributing to growth thereafter, discretionary fiscal policy this time has actually acted to restrain the recovery."

According to Bivens’ research, the federal government spent 15 percent less four years after the recovery than it did in previous recessions.

“The recovery has taken so long mostly because of the contractionary fiscal policy that we’ve been passing through Congress since 2011,” Bivens says. Spending cuts like those under 2013’s budget sequestration have depressed overall demand in the economy, he says, serving to keep wages lower than they would have been in other recoveries.

A boost from fiscal measures is especially important for workers' wages, Bivens says, given the historic weakness of organized labor: "Full employment becomes the only game in town to get bargaining power."

Wharton School professor of economics Peter Cappelli, however, isn’t taken aback. “If we compared this to previous recessions, we’d say [wage growth] was surprising. Then again we’ve never had a banking-related crisis since the Great Depression. This is not a regular recession.”

Workers And Investors

One of the places where the Fed’s near-zero interest rate policy has had an undeniable effect is in corporate borrowing. U.S. firms have made the most of slim borrowing costs, racking up more than $1 trillion of debt in each of the last five years.

But it has been less clear whether that bond glut has actually led to increased levels of productive investment. Increasingly, economists and policymakers are raising the concern that corporations have foregone capital expenditures in favor of payouts to shareholders.

Between March and May, S&P 500 companies raised a record $58 billion in low-interest bonds specifically for the purpose of paying out dividends and gearing up share buyback programs, which buoy stock prices and satisfy investors.

Critics of the surge in stock buybacks -- which have totaled more than $2.5 trillion in the past six years -- argue that these shareholder rewards come at the expense of meaningful expenditures that benefit companies and the broader economy.

One of those critics is Laurence Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the largest money manager in the world. Corporate executives, Fink said in a March letter, “deliver immediate returns to shareholders, such as buybacks or dividend increases, while underinvesting in innovation, skilled workforces or essential capital expenditures necessary to sustain long-term growth.”

In February, a study from the left-leaning Roosevelt Institute found that over the past several decades, corporations have devoted more borrowed cash to shareholders and less of it to research and capital expenditures.

“Firms use cheaper credit primarily to boost dividends and stock buybacks,” wrote J.W. Mason, the Roosevelt Institute fellow who conducted the research.

To Cappelli, it’s the tension between investors' interests and workers' interests that will enliven the Fed’s debate. While investors are more concerned with the possibility of runaway inflation than wage gains, middle-class workers can stomach modest inflation if it means higher pay.

“Ultimately these Fed decisions are fairly driven by politics. Are you worried about protecting investors or worried about protecting workers?” Cappelli says. “That’s always the story. But the politics have shifted considerably in favor of the investors.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.