Federal Investigator On Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 Search: 'I Don’t Think They’re Going To Find It'

As the search for missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 extends into its fourth week, with the crucial black box ebbing in power with every passing day, it becomes more likely that the plane will never be found, say veteran federal investigators and search and rescue specialists.

“Unless they get lucky, I don’t think they’re going to find it,” former FBI Special Agent Jonathan Gilliam told International Business Times, referring to the Boeing 777 aircraft that vanished from radar on March 8 with 239 people on board.

The former FBI man, who is not involved in the search, has also served as a Navy SEAL and federal air marshal. He has been following the three-week search for the missing plane, which has since been narrowed down to a remote 200,000-square-mile region located 1,150 miles west of Perth, Australia, in the Indian Ocean.

“From the very beginning, this has been a flawed investigation,” Gilliam said, pointing to Malaysia’s slowness both in announcing that a plane had gone missing and in asking Australia to lead the search. “It’s an investigation that I don’t think countries like Malaysia are typically used to.”

Throughout the past three weeks, the search for the missing 240-foot airplane has evolved. With the plane’s transponder turned off, investigators have few clues to confirm its whereabouts. Background checks on passenger and crew members have been cleared. At first, search crews scoured the seas stretching from China to India relying on satellite imagery captured by countries like France, Thailand, China and the United States to determine if and where the plane went down. On March 24, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak announced results from a British satellite company, Inmarsat, that "Flight MH370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean."

Since then, the search area in the southern Indian Ocean has changed multiple times. An area located southwest of Perth was scoured by vessels and aircraft for a week until new information led investigators to believe the flight crashed further north.

For Aaron Halstead, a manager with the Royal Flying Doctor Service in Melbourne who has extensive experience in air and sea search operations, the quest to find the missing plane and provide family members with answers seems daunting at this stage.

“If they don’t find the black box and they don’t find obvious debris of where it’s gone down … who knows,” Halstead said referring to the fact that the black box recorder will stop emitting a "ping" after its batteries expire in less than a week's time. “It might be a challenging if not near impossible task to actually find the plane.”

Halstead has conducted numerous search and rescue missions over sea and has led several Antarctic expeditions that have crossed the section of the Indian Ocean currently under investigation. Just as there are stages of grief, a search operation undergoes similar changes, he says.

“I think the stages in a search cycle. The initial stages are very much along the lines of let the authorities do their job,” Halstead says. “I think there’s a stage of acceptance that the authorities are doing all they can, but sometimes I think the longer it takes, and you can see this with the relatives [of the passengers], there’s a disbelief of ‘why aren’t they finding something?’”

Military units from Australia, New Zealand, Japan, China, South Korea, United States and Malaysia have been tasked with trying to find traces of the plane. Once the search area was narrowed down to the southern Indian Ocean, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority has been asked to helm the investigation. The search operation is headquartered in Perth, on Australia’s west coast, where a command center that resembles a NASA control room has been set up. Any critical lead picked up by spotters in the air or in vessels is tracked, Halstead explains.

In the field, sophisticated equipment is in play. This includes Lockheed P-3 Orion and Boeing P-8 Poseidon aircraft, which are typically used to hunt submarines. In the sea, anywhere between eight to 10 ships are dispatched to search for the missing plane. The U.S. has also sent a Towed Pinger Locator to find the plane’s black box.

With at least seven countries volunteering their military assets for the search, coordinating an effort on this scale has involved a “huge international level of cooperation,” says Graham Edkins, former air safety investigator Australian Bureau of Air Safety Investigation, pointing to military, civilian and scientific bodies that have shared intelligence that could aid in the search.

Working with other militaries is nothing new, Gilliam says. “We all do coordinated training together. We do war games together. They go through a lot of our training,” he says describing exchanges between the United States armed forces and allied countries like Australia and South Korea. “There’s a very harmonious relationship we have with different countries. It’s very viable and it proves itself when you have situations like this.”

Gilliam says the challenge does not lie with the idea of working with another country’s armed forces, but with executing it.

“You can take a thousand of the greatest, most highly trained, motivated crews in the world, but if you’re not tasking them in an efficient manner, they’re going to show up to the fight too late and they’re not going to do much good,” he said, adding that an established international protocol for aircraft disasters might result in a smoother investigation. “I think that’s the thing, besides the lack of tracking, that has hurt this the most: There’s just not enough coordination. This investigation has been 100 percent reactive instead of active.”

With 26 nations involved in some capacity – volunteering military resources, surveillance data, or the opening their territorial waters and airspace – tenuous relationships between sparring countries have complicated the response.

In particular, China has been reluctant to share its raw radar data, perhaps to hide its military capabilities.

“You had a lot of games going on,” Gilliam said describing the beginning of the MH370 search. “China, for instance, wanting to be involved, but not wanting to give away secrets where their satellites were pointed or were not pointed. The same thing with us. It’s not necessarily where our satellites are pointed but where they are not pointed. That’s a huge telling thing.”

Mapping the world’s oceans is a “globally collaborative effort” where researchers from around the world tap into shared databases, Robin Beaman, a marine geologist at Australia's James Cook University, said. Research vessels share the information they recover on their expeditions.

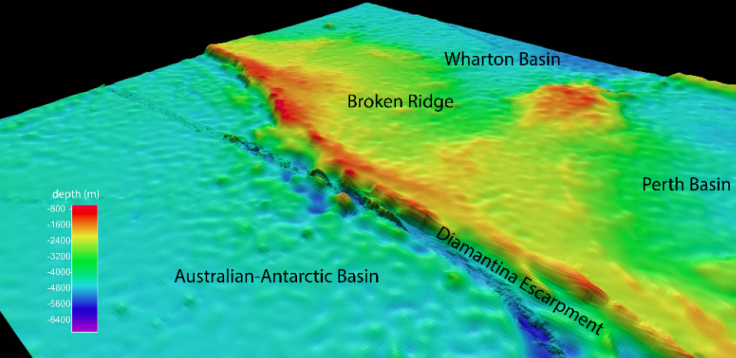

It is one such mission that has given search crews a picture of what the seabed looks like in the area west of Perth. The 200,000-square-mile region lies over Broken Ridge, an underwater volcanic plateau in the southeastern Indian Ocean 1,150 miles west of Perth. The only detailed mapping of the area happened by chance a decade ago when an American research vessel used modern sonar mapping to capture the Diamantina Escarpment – a cliff that drops to a trench with depths that can reach more than 16,000 feet. The rest of Broken Ridge has been mapped using satellite gravity imagery, Beaman said.

“My best guess is at the seafloor it’s relatively flat. There are not many lumps and bumps,” Beaman said. “If it comes to looking for any black box recorder, I imagine it would be an easier place to look for any crash debris in any kind of seafloor environment compared to the previous site. However, if they end up looking anywhere near the Diamantina Escarpment, that’s really difficult.”

Beaman, who is not involved in the search, has been curious about the plane’s mysterious disappearance since the news broke.

“I can only speak for myself,” he says. “It just seems we’re on the verge of a breakthrough, but with every day it’s another day lost and another day closer to a shutdown of this black box recorder.”

Despite this, Beaman sees hope in the collaborative efforts amongst the nations involved in the search.

“The ocean recognizes no nation. It’s a daunting, difficult place to do business in, and here we are all working together to try and solve a problem. I think the legacy of that will carry through for many years.”

Halstead, who knows the stretch of water currently under investigation well from previous expeditions, understands the challenges spotters are up against. He describes the expansive stretch of water, unimpeded by land with massive swells that would make debris hard to spot. With his experience and present knowledge, he anticipates the arrival of the third and final stage to a search and recovery mission.

“I do know that everyone is doing their best to find traces of the plane,” he said. “I think there will come a time that if this drags on, and nothing visible is found, I think people will start to question.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.