Why ‘Hostility’ To Banks And Bankers Is Healthy For The Global Economy

Leaders of the world’s largest banks have been desperately trying to escape the ghosts of the financial industry’s bad old days -- Libor rate manipulation, tax avoidance, rogue trading, swap misselling and the breaking of antimoney laundering rules -- and rebrand the industry as a responsible force for good in the economy.

Well, good luck with that.

Barclays PLC (NYSE:BCS) Chairman David Walker recently fired back against what he said has become the “political and media industry” of badmouthing banks and bankers, and insisted on banks’ irreplaceable role in a free-market economy.

At the economic Conference of Montreal on June 10, Walker said:

“The persistence of hostility to banks and bankers, much more marked in Europe than elsewhere, is in my view seriously unhealthy.”

Adding:

“The function of banking needs to be recognized as a key contributor to recovery in a developed world, in which credit is principally extended through the banks and the market rather than through state-run conduits.”

U.K.-based Barclays, unlike many of its American rivals, weathered the financial crisis without a government bailout. But this doesn’t mean that Britain’s second-largest bank can take the moral high ground. While Barclays didn't receive a pound of taxpayers' money, it benefited immensely from the emergency measures introduced by the government to prevent a sector-wide collapse.

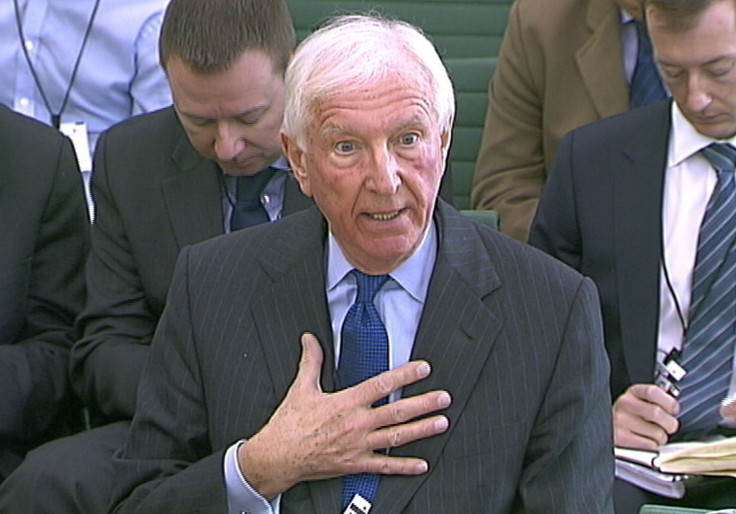

As John Varley, the former chief executive at Barclays, conceded in 2009:

"There are two ways I would say the system as a whole benefited generically. One was in the injection of liquidity undertaken by the Bank of England and a new structure put in place in March 2008. And the other was the making available of guarantees from government for funding undertaken by banks … I'm not trivializing the importance of the intervention. It was important.

From where I stand, one can’t really blame the public for not trusting greedy bankers who brought down the global economy, but still raked in eight-figure salaries last year. During the go-go years of the early 2000s, the traditional caution of bankers was thrown aside and a dash for expansion, fueled by lending and financial engineering, took hold.

As a historic, trustworthy investment bank, Lehman Brothers survived the Civil War, Great Depression, two world wars and Sept. 11. But it couldn't survive what it had become in recent years -- an “out-of-control” profit-chasing machine.

Lehman collapsed in the early hours of Sept. 15, 2008; in the following days and weeks, so did some 30 banks around the world. The key to Lehman’s failure was, of course, leverage (greed). By the time Lehman failed, it was funding portfolios of mortgage-backed securities, or MBS, with overnight debt leveraged 31 to 1 -- $22 billion of equity supporting $691 billion in assets. Anyone with a handle on fifth-grade arithmetic knows that it only takes a little more than a 3 percent decline in asset values and it's game over.

The “hostility” that Walker deemed “seriously unhealthy” actually serves as a constant reminder of the darkest hours of the Great Recession. Banks and bankers need someone outside of their circle to watch over their shoulders because the financial industry’s one and only goal is to maximize profit.

The banking industry has a short memory.

As soon as the dust began to settle after the greatest economic crisis since 1929, Wall Street is back to its old tricks, weaving together the same type of complicated financial instruments and mortgages that wreaked havoc during the housing bust. In the first quarter of this year, banks issued about $26 billion in new collateralized loan obligations -- more than in the same period in 2007, according to S&P Capital IQ. The New York Times reports demand for the loan pools has been so brisk that banks have been able to loosen underwriting standards on the underlying loans and bonds. This led to the Federal Reserve’s warning that “prudent underwriting practices have deteriorated.”

While banks are denying vigorously that they pose a threat to global stability, evidence points to the opposite conclusion. So, sorry if the public is being “hostile.”

Read this, twice if necessary:

“If you’ve got thin skin, you shouldn’t run a bank” -- John Varley, former CEO of Barclays.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.