'Flawed' Graphene Could Lead To Better Fuel Cells

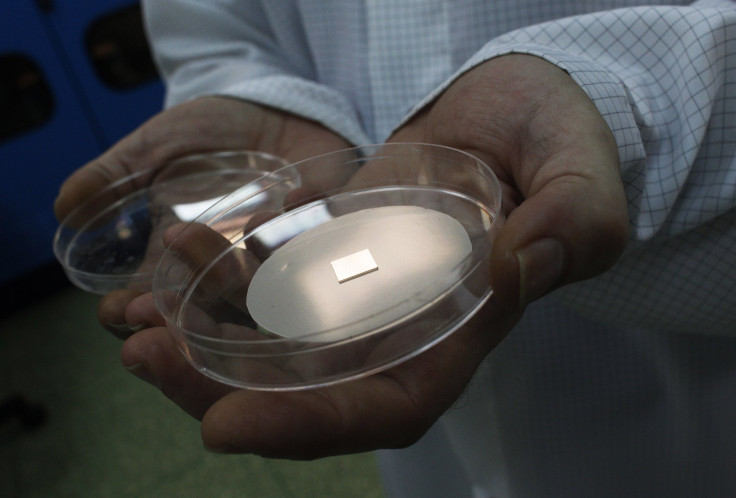

Graphene, the atom-thin sheet of carbon, has been found to increase the efficiency of fuel cells if its structure is imperfect, leading to new possible uses for the material. Tiny imperfections in the material’s honeycomb structure have been found to act as a way to separate oxygen and hydrogen in water.

Researchers at Northwestern University found that an imperfect layer of graphene combined with water allowed protons -- and only protons -- to pass through the membrane, in a matter of mere seconds. The imperfect graphene’s selectivity and speed are significantly faster than other membrane designs, the researchers said in the study, published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

"Imagine an electric car that charges in the same time it takes to fill a car with gas," Franz M. Geiger, who led the research, told Phys.org. "And better yet—imagine an electric car that uses hydrogen as fuel, not fossil fuels or ethanol, and not electricity from the power grid, to charge a battery. Our surprising discovery provides an electrochemical mechanism that could make these things possible one day."

The researchers noted that the imperfect graphene membrane is now the world’s thinnest proton channel. "We found if you just dial the graphene back a little on perfection, you will get the membrane you want," Geiger reportedly said. "Everyone always strives to make really pristine graphene, but our data show if you want to get protons through, you need less perfect graphene."

Manufacturing graphene remains highly expensive. However, recent breakthroughs in the production process are expected to dramatically reduce costs once they are widely applied. The discovery could open the way for hydrogen fuel cells, which would be more powerful than the existing ones.

“Our surprising discovery provides an electrochemical mechanism that could make these things possible one day," Geiger reportedly said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.