Ghana Gold Town Yet to See Gains

(REUTERS) -- Tucked away in Ghana's southern Ashanti region, Obuasi has all the trappings of a gold-rush town, including a statue of a miner painted in gold and a huge conveyor belt crisscrossing the city centre.

But while rows of neat miners' cottages show some local gain from a commercial mining industry dating back to the 19th century, many of its residents complain they have yet to feel the full benefit of the riches buried beneath their feet.

The costs outweigh the benefits, said Hayford Pajess, a 19-year-old high school graduate selling mobile telephone scratch cards in the unlit city centre streets.

Because of the mining, farmers can't do their work, the water is not good enough, and the air is filled with dust. There is no hospital or university, complained Pajess.

Even the city fathers add their voices to such grievances, acknowledging that the poor state of the city's roads and water supply jars with Obuasi's standing as one of Africa's premier gold mines with annual output of 317,000 ounces.

Obuasi is a 114-year-old study of the impact of mining, John Alexander Ackon, chief executive of the local municipal assembly, told Reuters, referring to the 1897 founding in London of the first major commercial operator, Ashanti Goldfields Company.

All over Ghana you see that most of the mining towns are in bad shape, he said of a country named by British colonialists as Gold Coast Crown Colony and which today is Africa's second-largest gold producer after South Africa.

With an election due in Ghana next year, the government of President John Atta Mills is trying to counter such perceptions by increasing corporate taxes on mining companies to 35 percent from 25 percent and introducing a separate 10 percent windfall tax on mining profits.

While Ghana joined the club of oil exporters a year ago, it says it also must get a better deal from exploitation of its metals resources to fund the higher standard of living its 24 million population is increasingly demanding.

JOBS FOR OUR BOYS

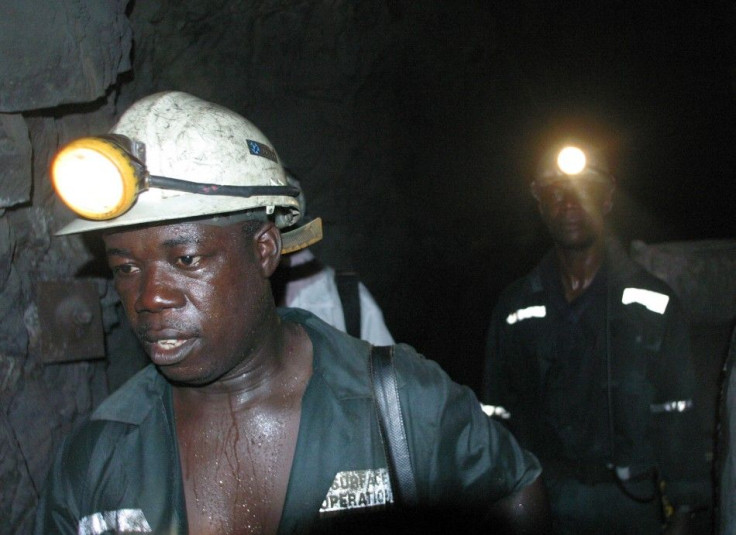

Now operated by South Africa's AngloGold Ashanti, the Obuasi mine employs 5,722 staff including contractors, who with their families make up a big chunk of the 115,000-plus local population.

Miners told Reuters the housing was the best thing about the job, with a family dwelling of two bedrooms, a kitchen, bathroom and living room with electricity and running water.

But many thought their pay insufficient.

The house is good, but I can't feed my mother, father and family on my accommodation, said one 46-year-old man with 30 years of work at the mine and three children, referring to a common expectation that a wage-earner support an extended family.

He declined to be named or reveal his salary for fear of losing his job, but the national union puts average pay at $475 a month plus benefits that take the total up to $800.

According to the World Bank, income per head in Ghana averages $1,230 a year, a level at which a miner's basic average salary could just about sustain a family of five. Union leaders say they will seek pay increases in 2012.

Life is even more challenging just outside Obuasi, where local chiefs say they have nothing to show for the fact that mining companies have snapped up land concessions.

The mining company needs to employ our boys, said 70-year-old Kwasi Addie, deputy community leader in Apitikokoo, one of the cocoa farming villages linked to Obuasi by the pot-holed Danquah Road.

We have no toilets, or running water, the doctor is 4 kilometres (2-1/2 miles) away, and the road to the main road is terrible, Addie said.

The 2012 corporate tax increases feed into a long-running debate about who picks up the tab for improving the lot of ordinary Ghanaians who live around the mines and beyond.

Ackon at the municipal assembly praised AngloGold for being more involved in local projects than other companies, citing the recent construction of a $10 million arsenic recovery plant and some work on road building.

Previously, corporate responsibility programmes had been used to benefit particular people, but now they conform to the city's development agenda, he said, adding that more could still be done both by the company and local authorities.

Calls to AngloGold's local operation in Ghana went unanswered this week.

Commenting on wage levels, AngloGold Ashanti public affairs manager in Johannesburg, Alan Fine, said the company mostly set them according to national agreements with trade unions.

He also said the company did not expect to be immediately affected by the new taxes because of a so-called stability agreement it signed with the Ghanaian state back in 2004.

That keeps in place for 15 years the taxation conditions and other conditions agreed at the time, he said.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.