‘Gravitational-Wave Background' Hum Could Reveal Several Distant, Unknown Black Holes

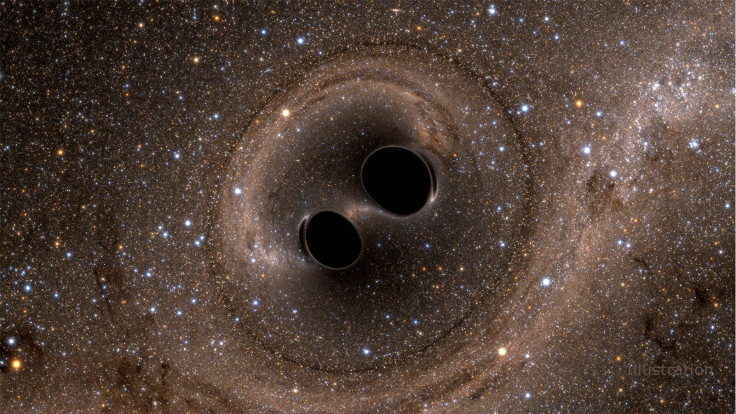

Black holes are those mysterious objects that devour everything in their proximity and produce gravitational waves or ripples in the fabric of space and time by colliding with each other.

Every few minutes, two of these voids merge and the waves from that cataclysmic event spread throughout the universe. But as all gravitational waves are not strong enough to be detected, many of these signals go unnoticed by conventional gravitational wave detectors on Earth.

However, that may not be the case for long as scientists have devised a way to “listen” to these ripples and identify black holes that have been hiding in the depths of the cosmos.

Ever since detecting gravitational waves for the first time in 2015 — from the collision between two distant black holes — astronomers have discovered just five more similar events. The count is incredibly low considering some 100,000 events are estimated to take place every year. Now, astrophysicist Eric Thrane, from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav) and Monash University, Australia, and his colleague Rory Smith plan to use these events by “listening” to their combined sound or the hum of gravitational-wave background.

Gravitational-wave background

Several weak ripples combine to form a gravitational-wave background, which can be converted into a sound wave. These sounds can then be analyzed with researchers' new algorithm, which listens to the sounds and identifies the ones made by black hole collisions. The idea is similar to picking a vehicle by the sound of its horn.

“I think it sounds a bit like a slide whistle. Look a 'whoooooooop' and then a sudden 'pop' when the two collide,” Smith told the Sydney Morning Herald, while describing what the sound of two colliding black holes would be like. To develop the algorithm for the sound waves, they ran computer simulations of faint black hole signals and kept collecting data until they were convinced they signified black hole merger.

The duo believes the new technique will yield better detection than other processes and that too in much less time. Notably, the method is also a thousand times more sensitive and could help astronomers identify many black holes collisions while revealing critical information about the voids involved in those mergers.

“Measuring the gravitational-wave background will allow us to study populations of black holes at vast distances,” Thrane said in a statement. “Someday, the technique may enable us to see gravitational waves from the Big Bang, hidden behind gravitational waves from black holes and neutron stars".

For now, the next step for the team is to look for gravitational waves in loads of data collected by Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory and pick black hole collisions from it.

The novel technique of gravitational wave detection has been detailed in a paper published in journal Physical Review X.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.