Greece and Germany: The Euro Zone Debt Crisis-Part 2

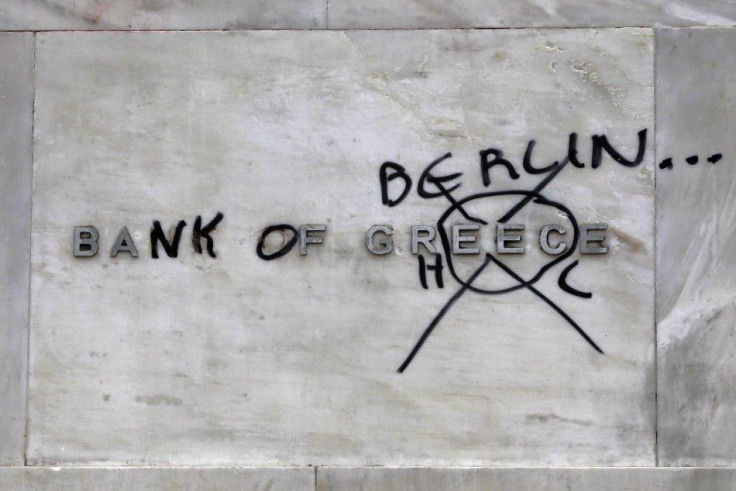

Mired in a deep and prolonged economic crisis, the much beleaguered people of Greece have apparently turned the bulk of their anger upon Germany, the most powerful economy in Europe.

The German government -- and especially Chancellor Angela Merkel -- are widely blamed by Greek politicians and ordinary citizens for being instrumental in punishing Athens with a crushing austerity program in exchange for a huge €130 billion ($170 billion) bailout from the European Union (EU).

With drastic cuts in spending, massive job losses, and reductions in pensions and salaries, the Greeks face a long, hard road ahead of them – and it appears Germany will bear the brunt of Greece’s composite anger and outrage.

According to a poll conducted by Epikaria magazine, 71 percent of the Greek public “dislike” Germany, while almost one-third (32 percent) of respondents compared Berlin’s current fiscal policies with those of the Nazis, who brutally occupied Greece during World War II.

Only 8.6 percent of Greeks polled held a favorable view of the Germans (who, not coincidentally, happen to be Athens’ largest creditor).

Moreover, recent negative comments about Greeks by some senior German officials, particularly finance minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, have exacerbated the ill feelings across Greece.

How deep is this Hellenic animosity towards Germans? And what is the historical background between these two countries at the opposite ends of Europe’s wealth spectrum?

International Business Times spoke with two experts on Greece to gain their insight onto this subject.

Artemis Leontis is an associate professor of Modern Greek and Hunting Family Professor of the Institute for the Humanities at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Mich.

Dr. Maria Hnaraki is director of Greek studies at Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pa.

(Continued from Part 1)

IB TIMES: Is the hostility reserved towards German government and banks, or does it extend to the German people in anyway (given that some German politicians and media outlets have insulted Greeks for being “lazy” and “undependable”)?

LEONTIS: I have not seen any evidence of Greeks attacking Germans as individuals except for Angela Merkel.

Indeed, Greeks want to keep peace with the German people, who bring good money to their country as tourists.

What I have witnessed are Greek politicians responding defensively to German criticisms of Greece's inability to raise revenue with heightened rhetoric of the who are the Germans to insult us? kind.

I have been following the escalating dispute between the Greeks and the Germans over the past few weeks quite carefully, and I am actually surprised to see how measured the political response in Greece has been.

For example, one can usually count on Greek Socialist politician Theodore Pangalos to say something quite immoderate. But even he never called the present-day Germans Nazis; rather he recalled the Nazi occupation to remind the Germans of their historical misdeeds.

In contrast, it seems some German newspapers and EU bankers feel they have free rein to say whatever they want about Greeks.

Also, while we have seen Greek protesters burn German and Nazi flags all of this seems pretty measured to me given that the discussions about the future of Greek debt have all concentrated on how to preserve the investment of creditors while moving to sacrifice everything the common Greek people once had -- pensions, wages, assets, services, even their national sovereignty.

In fact, Greek resentment is focused on German institutions specifically for the debilitating terms of the bailout.

HNARAKI: All in all, I would say, Greeks are blaming the German government and financial institutions and not the German people necessarily.

Keep in mind that Western and Central Europeans are very different from Southern and Mediterranean Europeans. The pejoratives used against Greeks have also been used to describe all southerners, including stereotypes projected by German tabloids or magazines like Focus which had an infamous cover in February 2010 that was insulting to Greeks.

As the German economic historian Albrecht Ritschl has pointed out, the “Wirtschaftswunde” (economic miracle) of Germany in the 1950s meant that the victims of the German occupation in Europe (including the Greeks) had to forego reparations.

IB TIMES: Do you think that some Greek politicians are helping to whip up anti-German sentiment in order to move attention away from their own failures in dealing with the crisis?

LEONTIS: Some Greek politicians are indeed recalling Nazi atrocities to counterbalance their own failures in their handling of Greece's finances, as if to say, the Germans don't have the right to criticize us for mismanaging money, given the “mismanagement” of the Nazi occupying forces in Greece 70 years ago.

The rhetoric is decidedly populist, and it appeals to the Greek people’s sense of the injustice that they must shoulder all the burden of the current debt crisis.

IB TIMES: Prior to the euro zone debt crisis, what kind of diplomatic-political-economic relations did Greece have with Germany?

LEONTIS: I don't think there were major tensions in Greece-Germany diplomatic relations prior to the debt crisis.

Until 1989 in particular, Greece and the former West Germany were allies on the anti-Communist front.

IB TIMES: What kinds of trade and business relationships have the Greeks and Germans had in recent years?

HNARAKI: There have been several commercial partnerships and transactions between the two countries.

Major construction in Greece was undertaken in collaboration with German vendors in public-private partnerships, such as the Athens International Airport (currently listed as one of the best in the world) that was established in the form of a partnership involving the Greek state and a private consortium led by the German company Hochtief AG.

German companies were heavily involved during the pre-Olympics infrastructure program (e.g. Siemens, etc.); on projects with ThyssenKrupp Group, the Hellenic Shipyards; the high-tech Hellenic Aerospace Industry with Eurofighter and EU drones; as well as several pharmaceutical agreements.

Also, a policymaking partnership like the Greek-German Economic forum of Thrace with the potential Special Economic Zone is currently operating.

However, some questionable practices, like pricing policy (in cases like the LIDL German supermarket chain) and penetration strategy (in cases like Siemens) have caused a great frustration amongst Greeks.

IB TIMES: In Germany’s post-war boom, the country accepted millions of guest workers, especially from Turkey, Greece and other southern European nations. Is there a sizable Greek community in Germany today?

HNARAKI: Yes, there is. The ironic part is that Greeks migrated there due to World War II and the Nazi occupation.

LEONTIS: Under the terms of a 1961 agreement between Greece and Germany, Greeks were allowed to come to Germany as Gastarbeiter (guestworkers). Each year tens of thousands of Greeks arrived, with the largest number of 50,000 arriving in 1970. The total number of individuals signing work contracts as Gastarbeiter was 382,000, according to the Goethe Institute Griechenland site.

Today, there are 354,000 German citizens of Greek descent, the fourth largest group in Germany -- 45,000 of them currently above age 60.

A further breakdown shows that 78 percent of Greeks living in Germany have been there for at least 10 years; 26 percent more than 20 years; 38 percent have been living there more than 30 years.

The numbers of recent Greek immigrants were much smaller when calculated a couple of years ago -- about 12,000.

HNARAKI: I should also mention here that many Germans have bought land in Greece, married local people and assimilated and identified with the Greek ways.

IB TIMES: Are young Greeks seeking to immigrate to Germany now given the lack of jobs at home?

LEONTIS: Greek newspapers are reporting that people today are lining up to learn German in Greece so they can leave the country, and many young people are trying their luck in Germany, looking for work they cannot find at home.

HNARAKI: I would think this is the case with young people all over Europe. I do not see Germany particularly as a potential job market for Greeks, given the language limitations, among other issues.

Germany is part of the open EU labor market that encourages the free mobility of EU citizens.

IB TIMES: Does the Nazi occupation of Greece during World War II still haunt Greek-German relations? Have the Germans ever apologized for their brutality and murders they inflicted during the occupation?

LEONTIS: The matter of apologies, reparations, return of the occupation loan, and individual suits for reparations and attempts to seek state immunity from individual suits is a complex one.

It must also be said that the Greek government has not been consistent in its pursuit of these things.

On the German side there have been separate apologies for certain acts. For example, I read a report stating that in 2000 the German president Johannes Rau visited the site of Kalavryta to express grief and shame for the civilian massacre. There was another apology for atrocities at Distomo.

However, there has not been, to my knowledge, a broad recognition or even a listing of the extent of brutality inflicted on Greece during the Axis occupation. Moreover the German Government believes that through various means it has adequately compensated Greece for the damage done.

HNARAKI: I do not think the Germans have officially accepted the acts they committed in Greece during the Nazi occupation. For example, they rejected having committed “unnecessary” atrocities in Distomo, as well as other reparations cases.

In bi-lateral relations, as noted in the recent resolution of the International Court of Justice on jurisdictional immunity, “accepting responsibility” and apologizing is not done through mere words, but should be a starting point for reparations and a willingness to pursuit negotiations. That is a path still to be paved from the German state.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.