Greece Running Out of Time as Euro Zone Ministers Mull Rescue

Euro zone finance ministers are expected to deliver their decision on whether or not Greece will receive its next tranche of bailout money on Monday, just weeks before Athens has to make a repayment on a 14.5-billion euro bond (or otherwise face bankruptcy)

While most observers believe Greece will indeed get the 130-billion ($170-billion) euro rescue package, it will come with powerful strings attached. Finance ministers from the wealthier members of the euro zone, fed up with Greece’s failures to implement past austerity and reform measures, will call for a more stringent oversight over Greek financial affairs.

On Wednesday, finance ministers from all 17 currency bloc members held a conference call (in lieu of a face-to-face- parley) to go over the Greek government’s proposed budget cuts which were already passed by the Athens parliament last weekend.

The new austerity package envisions about 3.3 billion euros in cuts, including thousands of job losses. However, the International Monetary Fund, European Central Bank and the European Union (EU) want even more cuts -- 325 million euros worth.

While acknowledging the “substantial progress” Greece has made in trying to put order to its financial straits, euro zone ministers demanded more cuts and a detailed plan on application of the austerity scheme.

Given that Greece is planning to hold elections in April, EU officials want a guarantee that whoever wins the poll will abide by the terms of the bailout package.

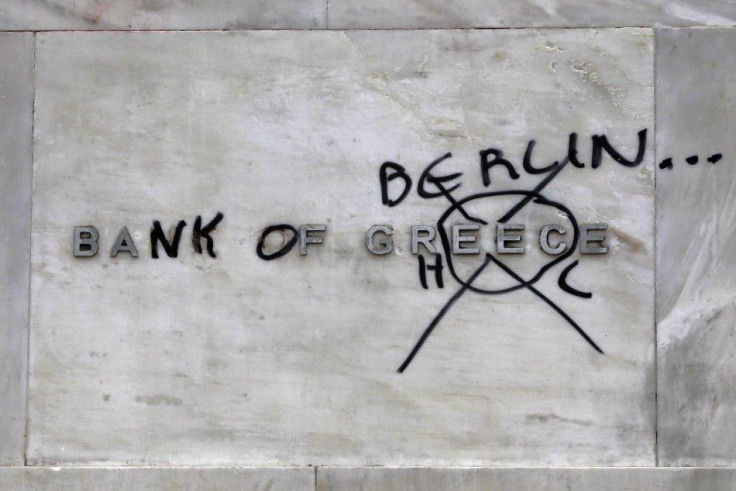

Chris Morris, a BBC correspondent in Brussels, wrote of the Greek affair: “Some [euro zone[ countries are demanding that the Greek economy must be put under much tighter surveillance, giving the euro zone far more control over what Greece does with its money. That reflects skepticism that Greece will be willing or able to deliver on its promises of reform. In return, angry comments have emerged from Athens about demands made in Berlin and elsewhere.”

Morris added that Greece’s finance minister Evangelos Venizelos has suggested some countries in the bloc want Greece to leave the eurozone.

“Chancellor Merkel still says she wants Greece in, not least because she fears the alternative,” he wrote.

“But if the eurozone manages to strengthen its bailout fund in the next few months, creating a more robust firewall to protect countries like Italy and Spain, then opinion could harden further. This current phase of the crisis could be Greece's last chance to stay in the euro-club.”

While it is clear that the Greek public is extremely angry about the continuing economic bad news and budget cuts, some senior politicians are also outraged by what they view as overbearing behavior by some western European figures.

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble seemed to taunt the Greeks when he told German radio on Wednesday ”we are not going to pour money into a bottomless pit.

In response, Greek President Karolos Papoulias said: I do not accept having my country taunted by Mr. Schaeuble, as a Greek I do not accept it.”

While many European officials are expecting Greece to eventually default, not everyone is concerned it would be as devastating as feared.

Julian Jessop, chief global economist at Capital Economics in London, wrote that the global fall-out from a Greek default alone should be small and manageable, even if it takes the form of a “disorderly” default without the agreement of private creditors or the other euro-zone members.

”A Greek default need no longer be a big deal,” he said. “In isolation it would be far less damaging to the global economy or financial system than the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. After all, Greece accounts for less than 0.5 percent of world GDP and the absolute size of its government debt is relatively small at around $455-billion.”

He added that unlike Lehman’s collapse, a Greek default would hardly be a surprise to the market.

“The prospect of default has long been reflected in the prices of Greek bonds and in the [credit default swap] market itself,” Jessop noted. “The ECB has already moved to cushion banks against the potential fall-out from a Greek default with its generous injection of liquidity.”

Jessop warns, however, that a Greek default could prompt other problems that would escalate into something serious for the entire euro zone.

“A Greek default could still be the start of a whole new and much more dangerous phase of the crisis in the euro-zone,” he said.

“A disorderly default would severely undermine confidence in the policymakers’ ability to tackle problems in much bigger economies like Spain or Italy. Even an orderly default might increase contagion risks, as it would establish a precedent and model for others to follow.”

Indeed, a series of rolling defaults and the ultimate break-up of the single currency itself would be quite another matter, Jessop added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.