Grueling University Entrance Exams Begin For Shrinking Pool Of Chinese Students

The Chinese seem to have a perverse love for taking exams.

It's ingrained into national traditions. In ancient times, imperial exam systems were the preferred method for finding capable new officials. Today, high scorers are applauded by families, schools, and peers.

It's now a sign of international status, too. Chinese students routinely trounce competitors in other countries in testing in core skills like reading, mathematics, and sciences. Over the next two days, they will also be sitting down for countless hours for the chance to compete against national peers and win a coveted place in a leading college or university.

So why has the number of Chinese high school students taking nationwide exams -- basically the only option to advance to college unless an individual's exceptional status (either through connections or intellect) excludes them -- continued to drop four years in a row?

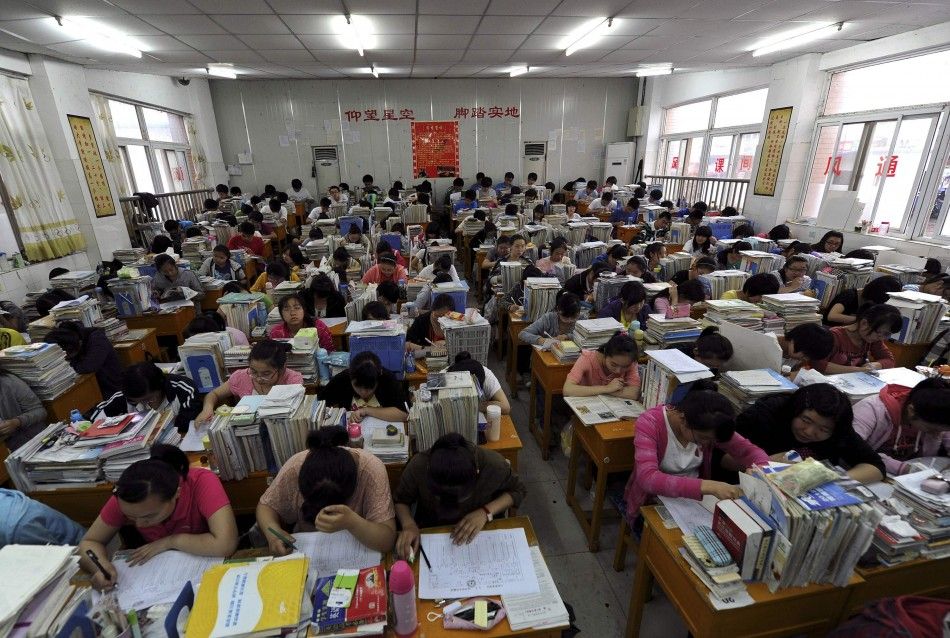

This year the Ministry of Education reports that 9.15 million students attended the exams on Thursday, the first of a two-day session of grueling trials that saw students preparing months in advance. Students take exams from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on both June 7 and 8, but have a three-hour break at lunch; most are in their senior year of high school. Subjects tested include Chinese, foreign languages, the sciences, the social sciences, and mathematics. The length and number of participants almost certainly makes it the largest examination system in the world.

But it's also an increasingly shrinking one.

In 2008, the government reported a historic high point of 10.4 million test-takers. So why did the number fall by more than one-tenth over the following years?

Experts believe the reasons are numerous. China's decreasing birth rate is one cause. In past years, fewer children have been born due to population restriction policies. Demographers say that lower numbers of students simply reflect general demographics. After all, the number of children born to each Chinese mother is now 1.56 according to the United Nations, well below the 2.1 figure generally thought to indicate stable population levels.

Most places that have shown growing numbers of test takers in past years are located in western provinces, where the government's new initiatives to improve primary and secondary education are now taking greater effect.

Another reason, immediately understood by students everywhere, but perhaps not readily obvious to those enamored with China's cut-throat education system, is that increasing numbers of students are simply fed up and see no point in it.

Increasing numbers of students and parents are now critical of the post-secondary education system in China, and are increasingly able to avoid it altogether.

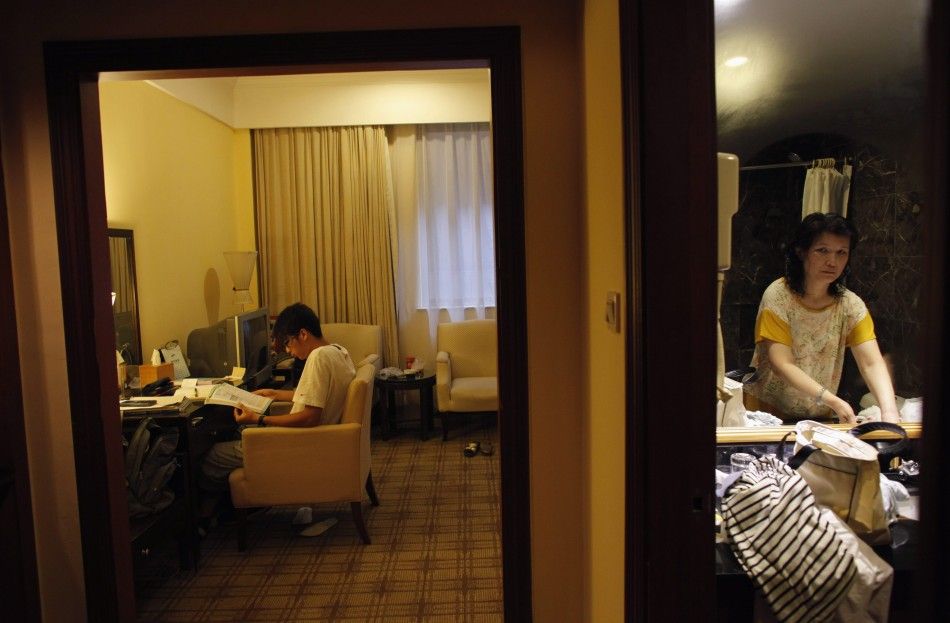

According to various Chinese media sources, 430,000 students will go abroad in 2012 (a figure that also includes graduate students). Larger numbers of well-to-do Chinese families are choosing to send their child abroad for a foreign education.

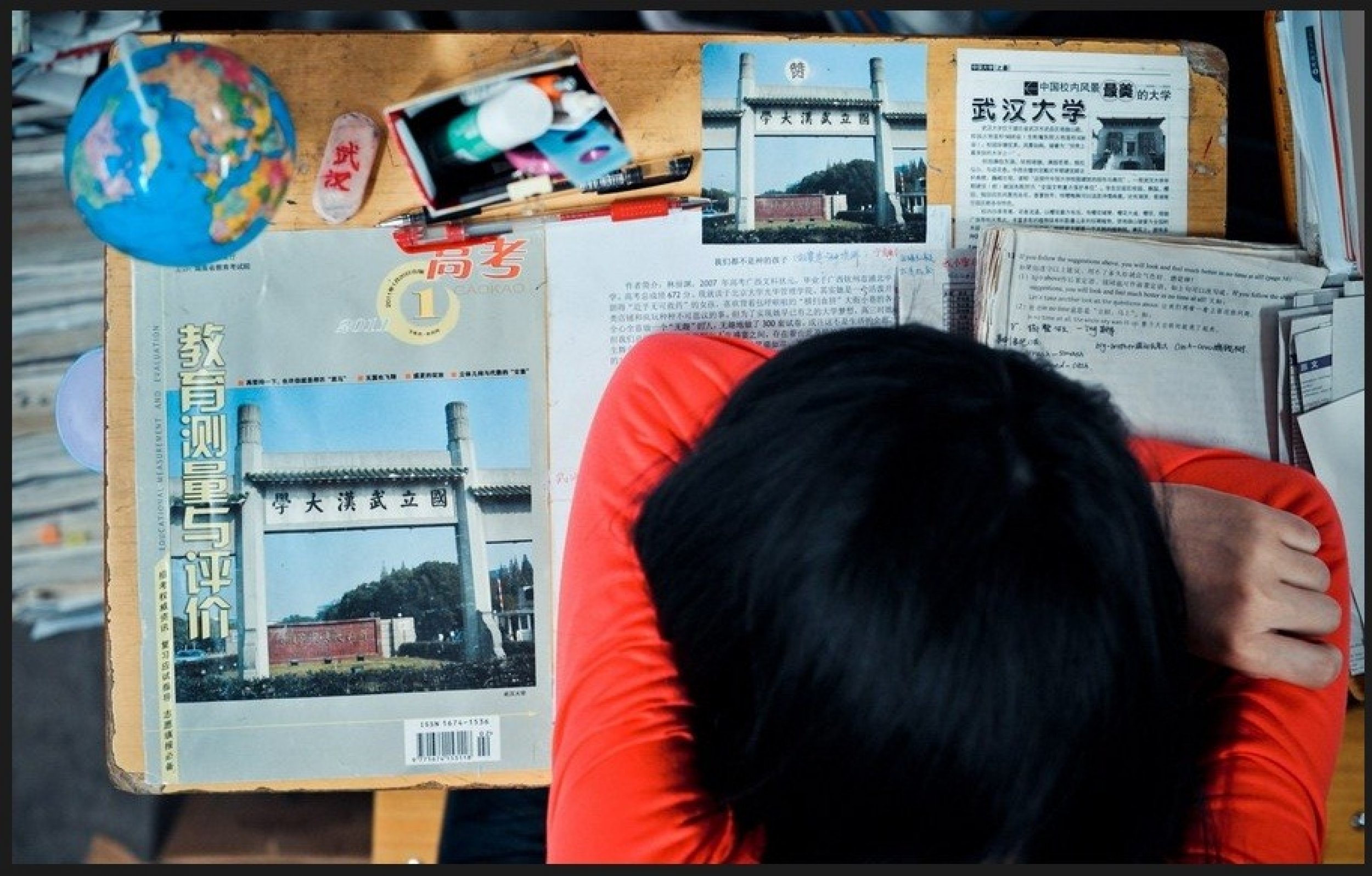

Others are just loath to go through the strenuous process of preparations, which require almost superhuman stamina. In Shanghai on Thursday morning, a 19-year-old unidentified student arrived at his test center, one of 7,300 in the country, with a medical team that stayed on site due to concerns about a collapsed lung. The condition first presented itself due to an overexertion in his studies on Monday. He will need to be hospitalized for another 10 days after exams are over. That's just one of numerous horror stories that are sure to emerge over the next two days. The term burnout doesn't quite seem to cover the extent of the tribulations of Chinese students, some of whom have, in the past years, committed suicide.

Yet others may choose to skip college entirely, since fewer numbers have faith that the value of a mediocre college degree will guarantee a stable or worthwhile job in a highly competitive post-graduation environment.

The last point perhaps, is the most worrying, since it reveals a more pessimistic attitude about the general job market in China and about the value of the education system.

It's an opinion not shared by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development's Andreas Schleicher, who is in charge of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), an international test that seeks to reveal comprehensive knowledge about a country's education system and its students performance. Students from Shanghai dominated all three categories (math, science, and reading) tested by the PISA in 2009.

Schleicher told the BBC that In China, the idea is so deeply rooted that education is the key to mobility and success. He added that in the country, more than nine out of 10 children tell you: 'It depends on the effort I invest and I can succeed if I study hard.

Schleicher says that unlike certain countries in the West, in China you get an image of a society that is investing in its future, rather than in current consumption.

He is almost certainly right that the vast majority of Chinese families still see education as a way forward in society for their children. Outside every test center in China on Thursday will be parents and families crowding entrances, waiting expectantly to hear about what their son or daughter thought of the day's endeavors. Even so, not all will go home happy. Only about 6.85 million spots in colleges and universities will be offered to this year's test takers, meaning a full quarter will simply have to try again in the future, or choose to bypass the process entirely.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.