Healthcare Reform 2015: As Pharmacists Push For A Bigger Role In Healthcare, Doctors Flinch

SEATTLE — Dr. Elyse Tung had to break the news to a patient this week that he is HIV-positive. The patient is part of a couple who visited Tung's clinic to discuss a preventive drug called Truvada that protects users from HIV. The couple have an open relationship and both scored high on an index that clinicians use to gauge risk for the virus. The man's partner started taking the drug three months ago, and had tried to convince him to begin treatment ever since.

The untreated partner tested positive for HIV during a mandatory screening in Tung's clinic, but he might also have been protected if he had started the regimen just three months earlier with his partner. Meanwhile, the man who was already on Truvada remained safe from the extremely high viral load that his partner was experiencing in the first months of infection.

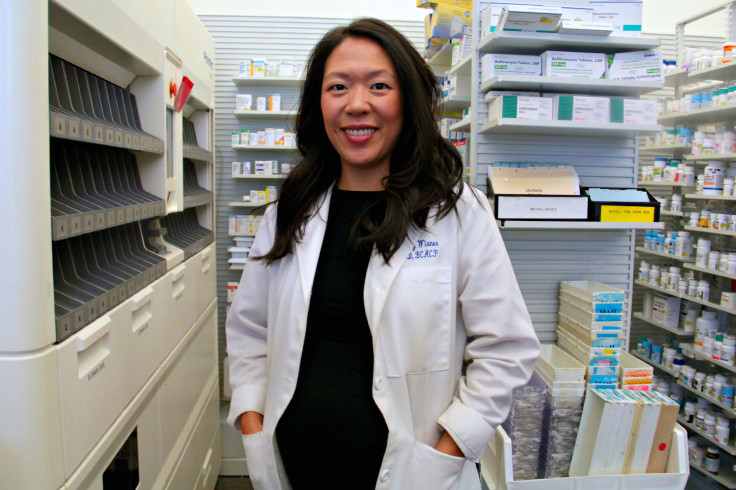

At first glance, Tung looks and acts like a traditional doctor guiding a pair of patients through a difficult medical issue. But she’s actually a pharmacist, and a professor at the University of Washington, who has launched a series of innovative care programs at Kelley-Ross Prescription Pharmacy in Seattle.

There’s a joke in healthcare that pharmacists are the most overqualified professionals in the industry. Pharmacy students learn to do everything from counseling diabetic patients to administering high-risk anticoagulation therapy. But once they graduate, most revert to dispensing pills because a pharmacy’s revenue depends on the throughput of medicine.

Tung wants to change all that. She and other advocates argue that allowing pharmacists to take on more responsibility in the healthcare system can expand patient access to medication, save money and improve health. So earlier this year, Tung purchased screening equipment and schooled herself on the appropriate use of Truvada. She began accepting patients at high risk for HIV at her pharmacy in March. Since then, 88 patients have received Truvada from her clinic in just five months compared with 15 in 2014.

“It's been way more successful than we ever imagined,” she says. To her knowledge, Kelley-Ross is the first community pharmacy in the country to dispense Truvada without requiring patients to visit a physician.

Tung says her program could catch on if state regulators across the country follow those in Washington state who have granted pharmacists permission to provide more services -- and bill insurers for those services, just like doctors.

“If we can do it, than any pharmacist can do it,” Tung says.

However, it's not so easy for pharmacists as eager as Tung to do more for patients in every state. For decades, doctors have staunchly opposed the idea that pharmacists should be trusted with greater responsibility. They worry that pharmacists will steal business away from their offices as patients visit pharmacies for services that doctors have provided.

In May, Washington became the first state to require that health insurance companies consider pharmacists as healthcare providers alongside doctors and nurses. That means pharmacists, as of Jan. 1, will be able to bill for their services just as a physician bills a patient for each appointment.

Already, pharmacists in Washington have provided clinical services that fall outside the scope of dispensing pills to 5 million patients in the past 15 years -- but weren’t directly paid for any of this work.

The campaign to earn reimbursement, led by Jeff Rochon, CEO of the Washington State Pharmacy Association, exploited a 1995 law known as the Every Category of Health Care Providers law. It requires insurers to cover at least one provider in every type of specialty. By arguing that pharmacists are healthcare providers, too, pharmacists persuaded officials that insurers were in violation of this policy. Many other states have Every Category of Health Care Providers laws and Rochon thinks pharmacists elsewhere will soon point to Washington’s law as a precedent to earn reimbursement.

A Pharmacist’s Duty

Pharmacists have long administered flu shots and ushered patients through smoking cessation programs. Supporters believe they should also be permitted to prescribe birth control, distribute Truvada and dole out travel medicines in states where this is not yet within their purview. Such tasks do not require a diagnosis; a patient simply needs to say that she wants birth control or will be traveling to a foreign country where malaria is endemic.

“Nobody really wanted to go to pharmacy school to count by fives,” says Dr. Kathy Hill Besinque, associate professor at the USC School of Pharmacy and former president of the California Pharmacists Association. “These are the things they really like doing -- taking care of patients. The more things that can be done to make that easier, I think the more pharmacists will do it.”

The idea of allowing pharmacists to provide more services is gaining momentum. Earlier this month, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown signed a bill allowing women to receive birth control directly from their pharmacists as of Jan. 1. California passed a similar law in 2013 that will take effect Oct. 1. However, neither state has passed a law similar to Washington’s that would reimburse pharmacists for the time they spend on these tasks.

Besinque thinks pursuing reimbursement is the obvious next step for California pharmacists. “If you're managing patients and you can't submit a bill, you can't really do it very long because you can't stay in business,” she says.

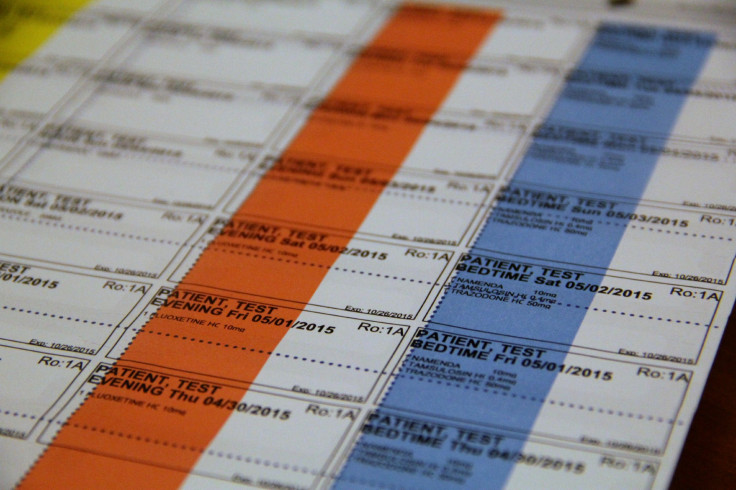

Elsewhere in the world, pharmacists are already completing extra services and receiving payment for it. The British government pays pharmacists $40 for 10-minute medication counseling. Switzerland pays pharmacists for the time they spend lining out a patient's medicines for the week.

U.S pharmacists note that reimbursing them for the time they spend on these and other services will save the healthcare system money. Rear Adm. Scott F. Giberson, a pharmacist who co-authored a 2011 U.S. Surgeon’s General report, has argued that every dollar spent on pharmacists saves the healthcare system four dollars.

A real-world demonstration of that concept, called the Asheville Project, took place in North Carolina from 2002 to 2005. The City of Asheville hired community pharmacists to counsel 620 employees on managing their diabetes for three years. At the end, 67 percent of employees had reached their target blood pressure. As a group, their risk of a heart attack or stroke was sliced in half. The overall cost of healthcare for both the city and patients dropped by 45 percent.

Harvard University’s Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation later found that a program modeled off the Asheville Project -- which sent diabetes patients to counseling from pharmacists, among other features -- resulted in lower blood pressure and levels of harmful cholesterol, greater patient satisfaction and a 10.8 percent reduction in healthcare costs.

Besinque says there are plenty of opportunities for additional savings. She cites birth control as an example: A pharmacist will simply prescribe birth control to a patient who wants it while a doctor may also conduct and bill for a Pap smear, even though these examinations are not required.

Gerald Kominski , director of the Center for Health Policy Research at University of California, Los Angeles, points out that physician and clinical services make up 20 percent of the nation’s healthcare spending, so cutting even a fraction of this expense by shifting services to pharmacists could make a difference.

“I think this is the kind of innovation we need in the healthcare delivery system in the U.S.” he says.

In Tung’s clinic, the service she provides is faster than what a primary physician can offer. Patients who visit a physician must wait for test results before picking up Truvada from a pharmacy. The process takes three to four weeks. Tung can run tests, prescribe the drug and dispense it in just an hour during a single visit.

Proceed With Caution

However, Devon Herrick, a fellow who specializes in healthcare at the National Center for Policy Analysis, worries that pharmacists will abuse their new power to bill payers, as doctors and nurses have done in the past.

"I don't have a problem with pharmacists counseling seniors on multiple drugs," he says. "What I would not want to happen is every single time a senior goes into a drugstore, there's an automatic charge to Medicare Part D and a claim to Medicare Part B for consultation."

Herrick is also not convinced that laws requiring insurance companies to reimburse pharmacists will catch on outside of Washington state. Insurers will likely oppose such measures because savings to the healthcare system do not directly translate to their bottom line.

“When pharmacists talk about charging for their consultations, what they generally mean is, ‘We know patients never pay us but here's a way for us to gouge the insurance companies,’” he says.

In January, legislators in both the House and Senate introduced bills to permit Medicare to reimburse pharmacists for some services such as medication counseling to seniors. Both bills were referred to committees and have remained there ever since.

Advocates who push to expand pharmacists’ roles in other states will also have to face off against doctors who have long begrudged the idea that pharmacists should take on more responsibility. The American Medical Association has opposed pharmacists' efforts to counsel patients on medicines, through a resolution calling it “pharmacy intrusion into medical practice,” and rejected the idea that pharmacists should have authority to write prescriptions.

“The American Medical Association encourages physician-led healthcare teams that ensure healthcare clinicians work together as the ideal way to provide high quality and efficient care. Pharmacists are valuable members of this team, and patients win when each member of their healthcare team plays the role they are educated and trained to play,” the organization said statement sent to International Business Times.

David Howard, a health economist at Emory University, says that stubborn stance doesn’t help patients or the healthcare system.

“It sets a bad precedent. They want to maintain the idea that all care must be under a physician's supervision,” he says. “It's more expensive and it limits the ability of the healthcare system to take advantage of alternative providers, and limits access to care.”

Pharmacists have learned to look for ways that reimbursement can benefit both fields, and presumably patient health, all at once. At Kelley-Ross, every patient is required to see a primary care physician within a year of participating in the Truvada program. Pharmacists say these measures are in the best interests of patients, though they also conveniently assuage doctors’ fears that pharmacists are stealing their business.

“There’s plenty of work for everybody,” Besinque says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.